Talking with singers: Christian Bowers

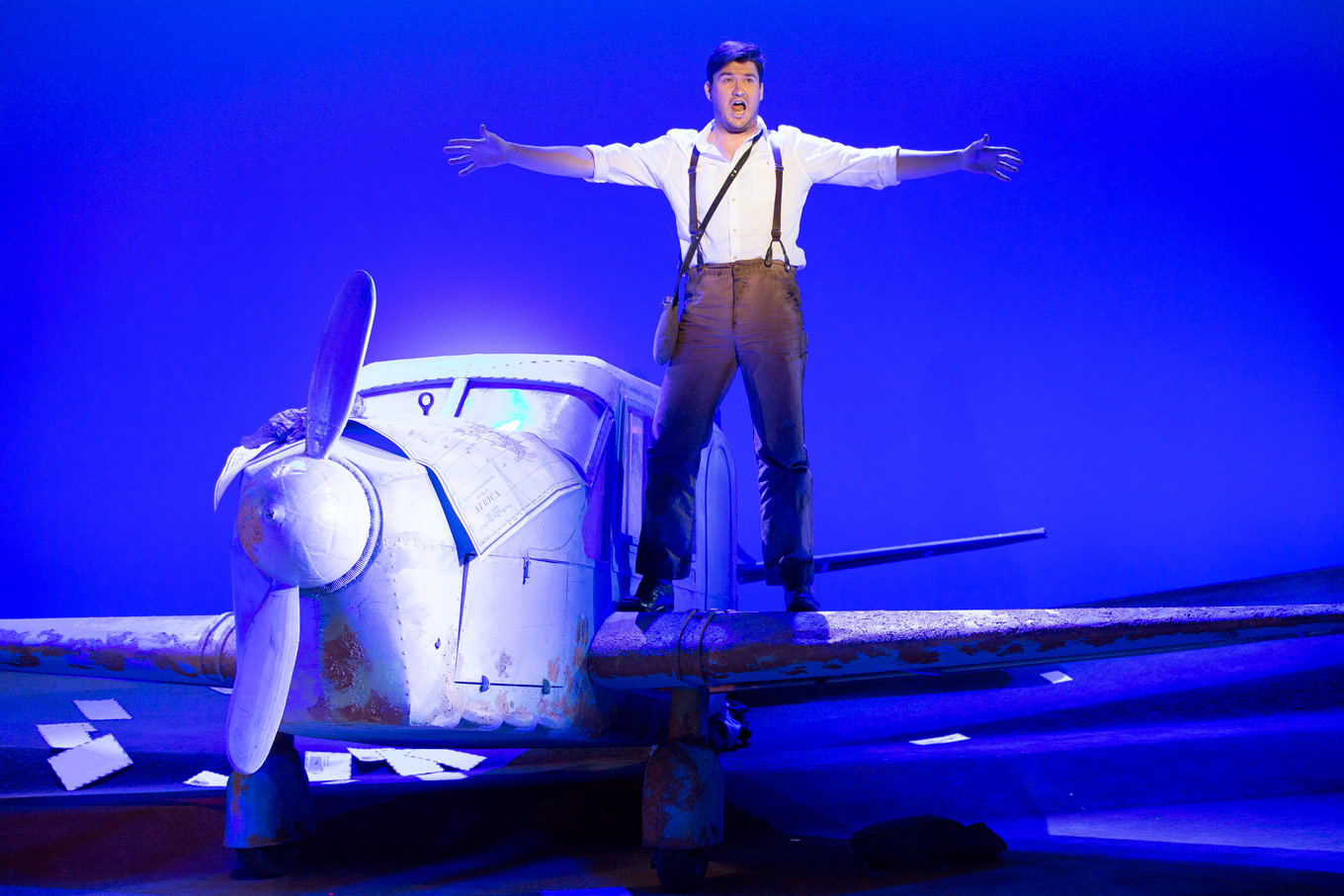

InterviewAmerican baritone Christian Bowers is mid-run of Utah Opera’s production of Carmen, where he sings the bullfighter with the famous aria, Escamillo. With his résumé full of roles like Dandini in La Cenerentola, Count Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro, and Maximilian in Candide, singing Bizet’s infamous Toreador seems an inevitable gig for the rising star. Yet for Bowers, his operatic work falls under a broader definition.

“When people ask me what I do, I say I’m an entertainer,” he explains. “I look back to Robert Merrill, John Charles Thomas, the classic American baritones. They weren’t pigeon-holed into just being an opera singer.”

“I’ve always loved to sing,” says Bowers, who grew up in upstate New York, surrounded by bluegrass and folk festivals, and enthusiastically involved in the talent show circuit. Perhaps it’s his wide view of how singing can move an audience that allows him to be relaxed in the face of pressure that can come with singing an iconic role like Escamillo.

“That stuff doesn’t bother me,” he says of the ancestry of baritones like Robert Massard, Samuel Ramey, and Dmitri Hvorostovsky who have sung the role. Bowers is aware of the “build-up for this character” that’s written into Bizet’s score, and how the anticipation centres on Escamillo’s very first notes. “It reminds me a lot of Barber, actually,” he says of the “entrance aria” formula that Escamillo shares with Figaro. Yet instead of comparing himself to his predecessors, Bowers has a simpler plan: “If you just own the character and go out there and have fun, the audience will have fun.”

Bowers will enjoy a healthy mix of genres over the coming months. After he finishes in Utah, he heads to Annapolis Opera to sing Emile de Becque in South Pacific, to the Kennedy Center for Duruflé’s Requiem, and to Toulouse to reprise Maximilian in Candide.

The shift from operatic roles to characters like Emile and Maximilian, which lay on the blurry borders between opera and musical theatre, doesn’t faze Bowers. “There’s no real shift. Maybe I brighten up the sound, slightly, it’s a little more spoken,” he says of his upcoming South Pacific. Along with straight theatre, Bowers has experience in operetta, and more recently, musical theatre. Yet he understands that for many singers centred in opera, it’s the spoken dialogue found in other genres that can be a daunting task.

“There’s a certain idea of, ‘I’m a singer, this is how I identify myself, this is my comfort zone,’” he says. “When you’re used to just being up there and singing with an orchestra, it’s completely different when there’s nothing under you.”

Though he has “always loved the dialogue portion” of theatre in any genre, it’s Emile de Becque’s French accent that’s currently at the forefront of his attention. “It’s one thing to pucker [your embouchure] and sound French, but when you have to fill a hall without a microphone, and still sound French, it changes everything.” With help from his French-speaking friends, Bowers is going for “sincere,” above all else.

“You have to love it.”

With over ten years of training from Temple University, the Academy of Vocal Arts, and the Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program at Washington National Opera, Bowers is one of the many working artists today who notices a dearth of attention on practical skills like acting. “It’s definitely not emphasized in most universities,” he says.

“I sometimes brainstorm with people about things that might be beneficial if I ran a music school.” Knowing how to run a small business - which is essentially what it means to be a singer - is another subject that demands more attention before entering the professional world. “No one really talks about that,” Bowers adds. To stay on top of things like managing a website, filing taxes in multiple countries, and dealing with contracts, “I’d recommend a business degree, or at least some business classes.”

It’s a hard thing to prepare for, but perhaps the biggest surprise for singers in their first few seasons out of training is the sheer amount of rejection they face, despite having put in the hard work. “Filling a calendar year is really difficult, and making enough [money] to rationalize being in this business is not always easy,” Bowers agrees. “But you have to love it, because it’s not about the money, at the end of the day.”

“As I talk with my fellow singers, it’s not necessarily something that you choose to do,” he says of the tough career. “It’s a vocation that chooses you.” Despite the rampant rejection and seemingly endless training that comes with the career, Bowers insists, “I can’t live without doing this.”

“It’s always been music.”

He recalls answering that age-old question in his high-school yearbook, about where he anticipated he would be, ten years after graduation. “I said, ‘Oh, I’ll be married with kids and singing at the Met,” he laughs, “because I was dumb. I didn’t know what it meant to be an opera singer.”

Though Bowers thought he would have a similar life to his classmates from back home, in that such-is-life way, his path went elsewhere. “I don’t have kids, I’m not married, and I’m not singing at the Met,” he says. And yet, “I’m no less happy.”

When he visit home, Bowers reconnects with family and school friends, and he can’t help but notice the differences between their lives and his own. While he understands that his life as a singer - with the travel and excitement that come with it - may be enviable to many, “I remind them that the grass is always greener on the other side.”

“There are a lot of times when I’m in an empty hotel room, and I’m looking at Facebook and I’m seeing you with pictures of your kids, the pictures of your house and the garden you planted,” he explains. “All my stuff’s in my room that I grew up in, and I live out of a suitcase or two for five weeks at a time.”

So, Bowers settles for balance. When he can, he takes the time to visit home, and work with his hands. (“I come from a family of carpenters and painters.”) When he’s on the road singing, he is comfortable with path he’s on, one that he says is “predestined.”

“For me, it’s always been music,” he says. “I was in school for ten years. I could have been a doctor or a lawyer, but instead I’m a singer.”

“I have no regrets.”

Comments