Talking with singers: Bryan Register

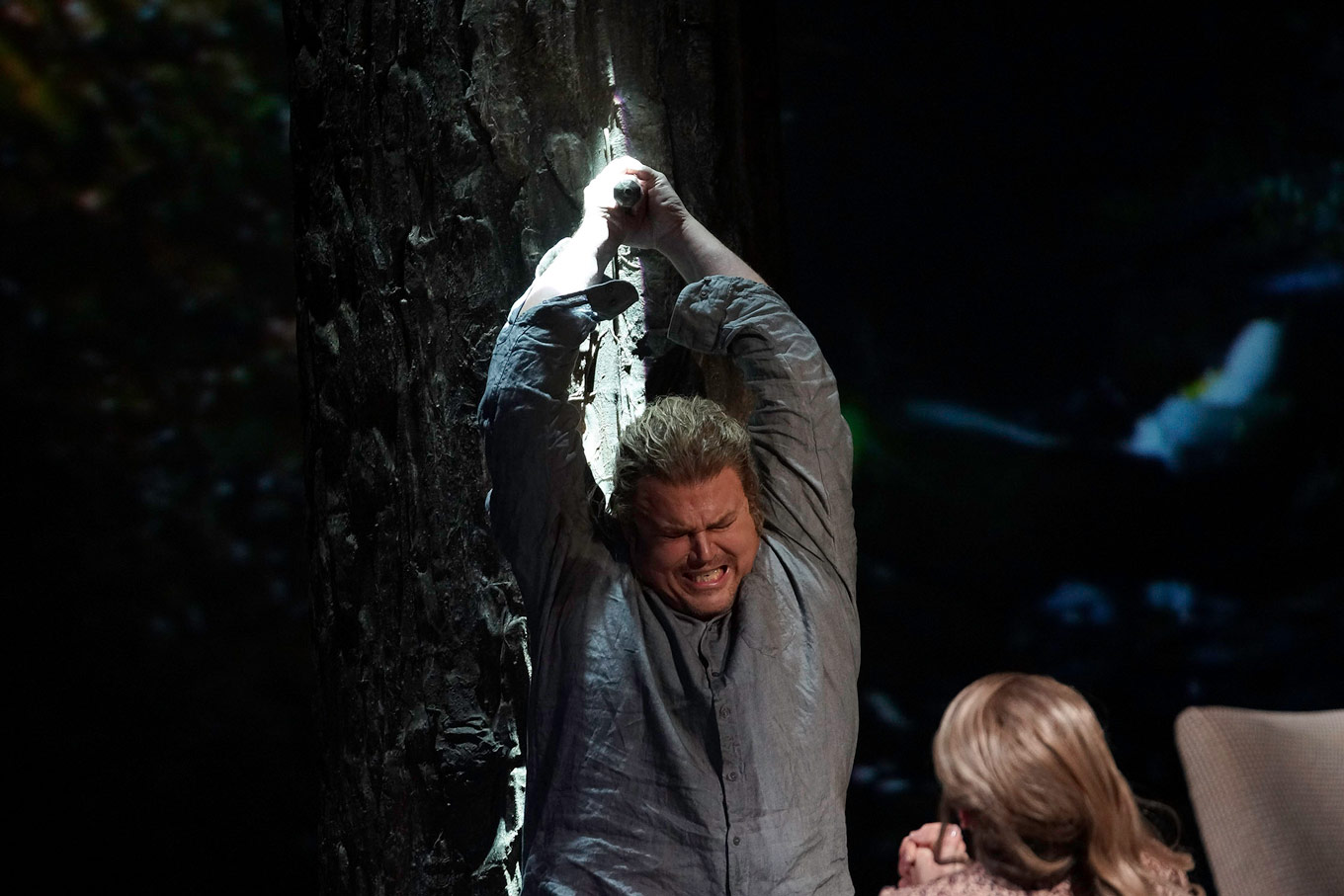

InterviewAfter getting a quick tour of his gorgeous Camden apartment, we had the chance to sit down with American Heldentenor Bryan Register. We caught him during some much-needed downtime between gigs, before he makes his company debut with Grange Park Opera in the title role of Tristan und Isolde. It will be his first performance of the role in the UK, and he’ll follow up his Grange Park shows with another Tristan in Tokyo.

Register’s repertoire includes some of the most enviable tenor characters in opera. Wagner roles like Lohengrin, Erik in Der fliegende Holländer, and both Siegmund and Siegfried in The Ring Cycle keep him busy, as do Bizet’s Don José, Beethoven’s Florestan, and Berlioz’s Énée. We were curious: what does it feel like to sing this kind of music?

“Physically, it feels like I’m doing my yoga practice in public, in front of an audience,” Register laughs. Singers and yogis alike know how tricky it can be to find a comfortable balance of effort and ease. “I would equate a long, difficult phrase, to holding a difficult pose in yoga. You just have to breathe into it, accept it, you’re not going to die.”

Register says that he used to make an association between his body’s working hard, and inadequate technique. “My back, my legs, all of my support system sometiems would be trembling or under a lot of stress.” Now, he recognises that “the feedback you’re getting from your body is simply because you’re using your body.”

The physical work involved is one thing, and the psychological work is another beast entirely. “Emotionally, it feels like I’m doing a pole dance,” says Register of the intense vulnerability that comes with singing onstage. “There’s always a flash in my head when I go out of, ‘oh I wonder if they like it, are they gonna like me, can I really do what I want to do, will they accept it?’ It’s only a brief flash, and when I start doing it, the thoughts aren’t there anymore.”

For many, the vulnerability involved in singing is a risk not worth taking, but Register knows the payoff that comes with the career. “The emotional rewards that I get from it, I haven’t found anything else that gives me that kind of a reward. The connection with the audience, and the feeling of that emotional exchange when I’m performing, I haven’t been able to find that anywhere else.” He doesn’t quite call it a religion, but it’s a spiritual practice in his life. “It’s cleansing, it makes me feel good physically, it makes me clear-headed, it makes me happy.”

“It was just working.”

“My parents were very concerned that I was going to go into a career that would leave me destitute and homeless,” recalls Register with a laugh. “So, our compromise was, ‘don’t give me a hard time about being a music major, support me on that, and then I will get my music education degree, so if nothing ever happens with my performing, then I always have a teaching degree and I can be a teacher.’”

His undergraduate placement exams included tests in ear-training and sight-reading; for the final part of the exam, Register was asked to sing the national anthem. The examiner’s eyes “got really big,” he remembers, and she called in another faculty member to hear him sing the anthem once again. “He said, ‘young man, you need to change your major today’.” It wasn’t until Register was offered weekly voice lessons, free of charge, that the gravity of the decision clicked. “I thought in my head, ‘Oh my god, he’s for real. He meant what he said.’”

He continued voice lessons, on top of his piano studies, throughout his undergraduate degree. “After about a year, maybe a year and a half, my voice started growing faster than my piano playing was. I was making more progress as a singer than as a pianist,” he says. “The piano, it prepared me perfectly for the singing, but I didn’t understand why. It felt so natural and organic, and it was just working.”

By the time Register was ready to apply for graduate schools, he did so as a tenor, not a pianist. “I was almost doing it as a dare, to see if what these people had been telling me was true or not.” True it was, and the positive feedback he received as a singer was confirmed when he was admitted, with full scholarship, to the Manhattan School of Music.

He says he never learned the exact amount of his scholarship, only that his graduate studies had been sponsored by an anonymous donor. “Maybe two weeks before I graudated, the dean called me to his office, and said, ‘you need to write this lady a thank-you note, because she paid for your education.’” He was more than happy to comply, and he remembers getting extra curious when the dean insisted that Register stay discreet about his sponsor. “He slipped me an envelope across the table. And I opened it up and it said Madam Birgit Nilsson, and then had her address in Sweden.”

Nilsson had heard his audition for MSM, and told the panel that he was set to be a Heldentenor. Register wrote her to thank her, and she wrote him back. “And I still have the letter.”

“I would have laughed in your face.”

“My tenor colleauges in school would come in with a flashy Rossini,” says Register of his early training as a tenor, “and it didn’t fit in my voice.” He questioned his own technique, and assumed he was doing something wrong. Following suit with other tenors his age, he worked on Mozart, Schubert, and vocal chamber music, deeming himself not quite ready for operatic arias. “I never did anything bigger than Donizetti,” he says, but he was aware that the repertoire wasn’t a true fit, and that he wouldn’t be hired for lighter tenor roles.

He first began exploring Wagner and Strauss on the advice of his teacher, despite his fears that the repertoire would significantly shorten the lifespan of his potential singing career. Eventually, he sang some Wagner for Matthew Epstein, who agreed that Register was on the right track; he set up an opportunity for him to sing for Evelyn Lear and the Wagner Society. He spent a handful of years in the programme, and began studying with the late Patricia Sage, “who really finished that prep journey.”

“If you had asked me when I was young, ‘Do you think you’ll be a Heldentenor when you’re older and be singing Tristan?’ I would have laughed in your face.” In hindsight, says Register, “it all makes sense. Of course Rossini didn’t fit my voice, of course it didn’t work, because it didn’t fit my body properly.”

“I always make a joke that for years it felt like somebody was telling me to wear pumps that were too small, and then insisting I walk like a lady. It ain’t gonna happen; it’s gonna be a hot mess.”

Young singers often equate a certain age with a ticket into “heavy” repertoire, but Register has discovered that there’s much less of a connection than is commonly perceived. “Age does not change your fach, necessarily. As you grow, your voice is going to change and mature, but bascially it’s not goint to completely transform into something it never was.” His comfort in Heldentenor repertoire seemed at odds with his age, and he was hesitant to accept his own readiness for “big roles”.

He looks back on Birgit Nilsson’s early recognition of his potential with a retrospective understanding. “I think now that I’m older and I actually do it, I could hear how she could hear a younger singer and connect immediately to that feeling of ‘He’s one of us’.” He posed that there is often an incomplete message delivered to young singers about the “horror stories” of tackling repertoire like Wagner. “If there was some sort of explanation, that ‘you’re doing this now, and you’re learning a lot about your body, you’re building your instrument through this repertoire, and someday I think you might do this repertoire,’ that’s a completely different approach than, ‘you’re 25, so you need to sing Mozart and you need to sing some Handel, and that’s what you do because you’re 25’.”

Advice and “that little inside voice.”

Register seemed a great person to ask about one of the big questions that singers face during their careers: how does one distinguish the good advice from the bad? His answer is concise, if not simple: “the one person you really have to listen to is yourself.”

“When we turn to a teacher, an agent, for advice, usually what we’re doing is looking for validation to an answer that we already know,” he explains. “You can’t ignore advice or input from people, because it’s also how you grow. But the most important thing is to listen to what your body’s telling to you, and to that little voice inside you.”

That “little voice,” he insists, is one that needs to be heard in every choice a singer makes throughout his career. “If you’ve made the decision based on that little inside voice, and you take responsibility for that and it doesn’t work out, at least you know, ‘Ok, I made that decision, that was my responsibility. it didn’t work out. I can’t blame anybody else for that.’ But if you do it just because somebody else told you to do it, but you didn’t believe it was the right thing to do on the inside, and it doesn’t work out, it will haunt you to the end of days.”

Like that feeling of doing yoga in front of an audience, or doing a pole dance onstage, taking risks in decision-making is what creates an honest performance. “I think that’s what makes you an artist, having to be that brave and that vulnerable and that ballsy.”

For full details about Tristan & Isolde at Grange Park Opera, follow our box office links below.

Comments