Aria guides: Embroidery Aria

How-ToHave you ever been faced with an ugly truth that’s hard to deny? That’s the gist of the stunning “Embroidery Aria”, sung by Ellen Orford in Britten’s Peter Grimes. She’s one of the few people in her small English town who is sympathetic to her friend Peter, and the ostracism he’s feeling from his community; yet when she finds the sweater that belonged to a young boy that Peter enlisted to help on his fishing boat, she’s forced to put her personal feelings for her friend up against what might be damning evidence of his actions.

The “Embroidery Aria” is no easy sing, and as you work on it in the practice room and with your teachers and coaches, we can help you get off on the right track with our latest Aria Guide:

- In case you needed another reminder that Britten is a genius, check this out: the most prominent method of word painting in this aria is also the key to singing it well. Like embroidery work, the winding tune should feel like an unbroken thread, where every twist and turn is accounted for. “Embroidery Aria” is written well for the voice, in that if the instrument is being used efficiently, the aria almost “sings itself”. Glossing over details - letting harmless sixteenth notes go un-sung - will make it feel difficult and lengthy. Get a great start on this first note, on “em-”, leaving lots of room for a vibrating vowel before you say the letter M; you can use a legato-friendly rolled R in “-broidery” to help connect that first note to the rest of the phrase.

- On the words “silken” and “dreams”, enjoy the trip between the high and low notes. At this tempo, there’s time to sing every pitch, and you can focus on bringing a good vowel down from the higher tessitura to those low F-sharps and Gs. One goal you’ll have in these two bars is to avoid “dropping” down towards a pure chest voice, so that you’re ready for the next phrase:

- Britten’s a genius, sure, but he’s not without his tricky bits. You’ll work with your teachers and coaches about the best way to approach this entrance on the high A; make sure you remember to include the G-natural in the mix, too, so that it doesn’t fall flat or lose its spin.

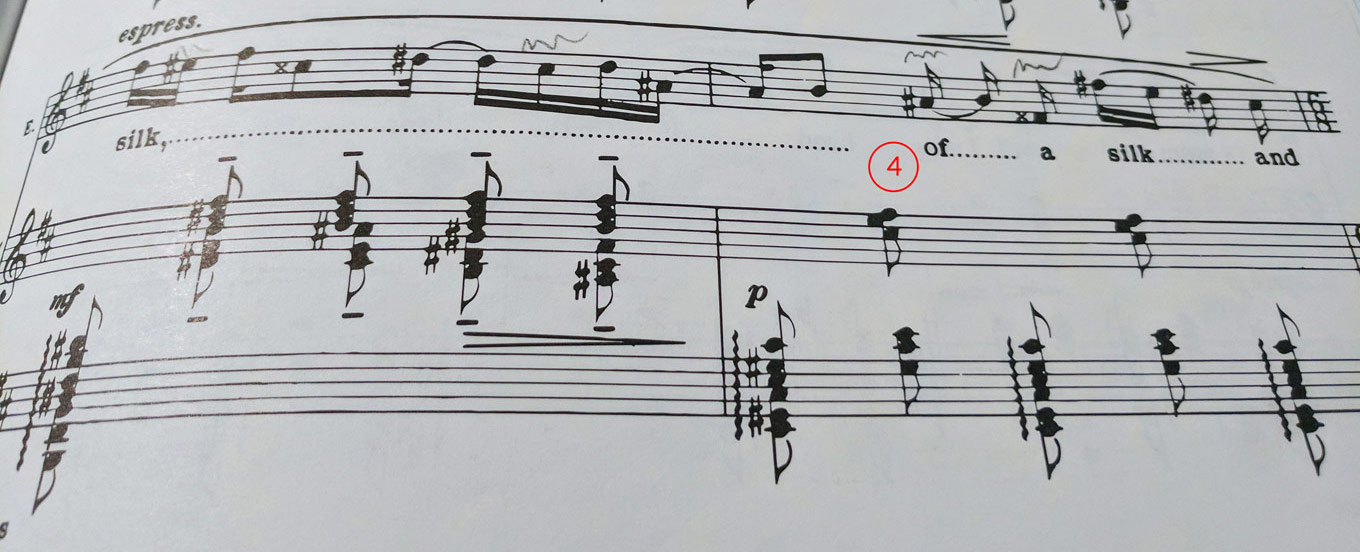

- These notes are super funky, so be ruthless with your intonation as you learn them. The big one is that interval between the F-double-sharp and high F-sharp on “a silk”; if you’re trying to make sense of the weird tune, remember the image of a moving needle and thread for some inspiration.

- This pattern comes up several times throughout the aria, and each time they’re scary; even when he seems unsympathetic to singers, Britten understands how the voice works. Many of the secrets to this bit lie in the lower pitch of “Now”, rather that the top. You want to find a buoyant version of the low B, one that will let you move up easily; it’s worth practicing the interval in reverse a couple of times, to really find what that lower pitch should feel like. Take the diminuendo with a grain of salt, and instead aim for a “non-crescendo” as you leap upwards. That means you can also give a bit of extra volume to the low pitch, so you have room to maneuver up to the G.

- Low Ds and Cs aren’t usually where sopranos like to hang out, so there’s a tendency to want to default to the chest voice in order to give “enough” volume. Chest voice isn’t necessarily a bad idea, provided you won’t get a yodelling effect when you leap up to the B-flats; for what it’s worth, the orchestra is marked più piano, so you have some wiggle room with volume. A better point of focus might be to once again remember the needle-and-thread image with your vowels, and to focus on clarity of text; words like “brooding” and “fantasies” have lots to work with.

- These two lines can be killer, if you let them. To help you find the big picture, use the harmonies in the orchestra and the pace of the text. “Only by wishing…” should feel like one part of a phrase, and “I could bring some silk into their lives” is the next part. It’s not easy to do, but thinking in speech-like terms will help you pace the meandering melody and keep you from getting bogged down or heavy. Take as many breaths as you’d like in this second half of the phrase; when you get to “into their lives”, make sure the accents are done in a way that helps you spin the sound forward. For “lives” itself, the bar can feel eternal; cut off the note when you need to, but if you think of renewing the [a] vowel in “lives” as the bar continues, you’ll find you have more in you than you might think.

- The same principles apply here to this “Now my broidery” as they did earlier in the aria. Because it sits higher this time, it’s even more important to pay attention to the notes that come after the high B-flat, in particular the first two notes coming down from it. The same applies to the subsequent “Now my broiderys” starting on the G-sharp and the G-natural. One last thing: remember that this is one of the few moments in a Britten opera where text gets purposefully repeated. By trying it out as spoken text, you can find reasons for Ellen to say these words over and over, in unfinished fragments, and with periods of silence in between.

Do you have an aria you’d like to see featured in our Aria Guides series? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch at [email protected].

Comments