"Vergesst uns nicht!": Adi Braun on Weimar cabaret

InterviewJazz and cabaret singer Adi Braun comes by music honestly. She was born in Toronto, but grew up in Europe, a part of a musical family that included two famed Canadian baritones, her father Victor Braun, and her brother Russell Braun. Adi too started along a classical trajectory, studying at the University of Toronto and the Royal Conservatory of Music, and singing with the Canadian Opera Company and Opera Atelier. Starting in the 1990s, she began “to sing sideways”, gravitating more closely to jazz and cabaret.

“Before I switched to jazz, or ‘Cabarazz’, as some people call it, I was a classical singer. Naturally I had heard of Kurt Weill when I grew up in Germany but it wasn’t until I heard the great soprano Teresa Stratas’ recording of Weill that I felt the impact of this kind of music and text and the possibilities it held for me.” Adi wasn’t happy singing this music with her classical sound, and so she retired the repertoire, temporarily. “Not until I was firmly established as a jazz vocalist did I look at it again and it was then that I decided to create my own ‘arrangements’ or musical interpretations of his music.”

Adi released Canadian Scenes I in 2010, her fourth album and her first foray into her work as a singer/songwriter; now, she’s writing her first song cycle in cabaret style, and she’s at the end of her first semester of the Doctor of Musical Arts program in Performance at the University of Toronto, studying cabarat music of the Weimar era. “I believe this field of European cabaret has never been studied or taught at a Canadian music school. I feel very lucky that at this point in my life I can be a performer, teacher and a student.”

Why cabaret?

When North Americans think of cabaret, we think of some level of counterculture, jazz-influenced music, and often a burlesque-inspired delivery. (More specifically, many of us think of John Kander and Alan Cummings.)

“All of those elements were also part of the cabaret culture in Germany,” assures Adi. American ragtime and early jazz music were big influences on German cabaret, and some of the American stars performed in Berlin’s cabarets. Cabaret was, of course, a source of entertainment; it was also a source of education. “The cabaret of the Weimar era provided a platform for many different types of performances and took place in literary cabarets, comedy clubs, and music venues,” says Adi.

In addition to the alluring music by composers like Kurt Weill (Bertolt Brecht was a poet) and Friedrich Holländer, Adi was drawn to the kind of cabaret songs in Germany that were more socio-political and satirical nature.”

“Of course Weill cannot really be classified as a cabaret composer,” she adds. “As a composer of vocal music he mainly wrote larger musical plays. But he lived and worked in Berlin exactly during the Weimar era and it is only nowadays that vocalists have taken single ‘hits’ from his musicals and added them to their cabaret programs.” Last year, Adi was invited to teach a short course at the Royal Conservatory of Music, on the history of cabaret. “I discovered in my research that there were a lot of things I didn’t know about the origins of cabaret and cabaret in general.”

Adi’s research uncovered new artists, new songs, and new vantage points into this kind of cabaret music, a genre that seems as insular as it is influential. “I found a great amount of fantastic songs by composers and poets and fell in love with the performers whose renditions I found on old recordings and YouTube clips. I discovered and am discovering so many different kinds of singers who we have now forgotten or never even heard of…so many daring ways of interpreting these brilliant songs and I was deeply touched by their art.”

A progressive cabaret scene

In the Weimar era, there seemed to be a cabaret for just about anybody. The dinner-theatre style of cabaret was common, says Adi, but there were also “comedy clubs, gay cabarets and political cabarets, [and] each cabaret likely had its own audience.”

The Weimar era brought much to talk about when it came to politics, and when it came to having a political function, Adi adds that cabaret was ultimately “meant to criticize the social mores of the times and to fore-warn of the impending rise of the Nazis.” It was an art form that wore its organic appeal and stylistic novelty as a kind of armour, allowing the songwriters and singers to talk about difficult (and often dangerous) topics.

Lyricists and composers worked as a team, almost branding themselves with their collective music and their message. “The relationship between words and music was of utmost importance and often had the distinct purpose of providing a socio-political narrative and critique.” More unique to Weimar-era cabaret was the rising status of the performer, as a sort of third party in the creative team. “The performer’s individual personality and performance magnified the messages the composer and lyricist sought to convey and they became important harbingers of their time.”

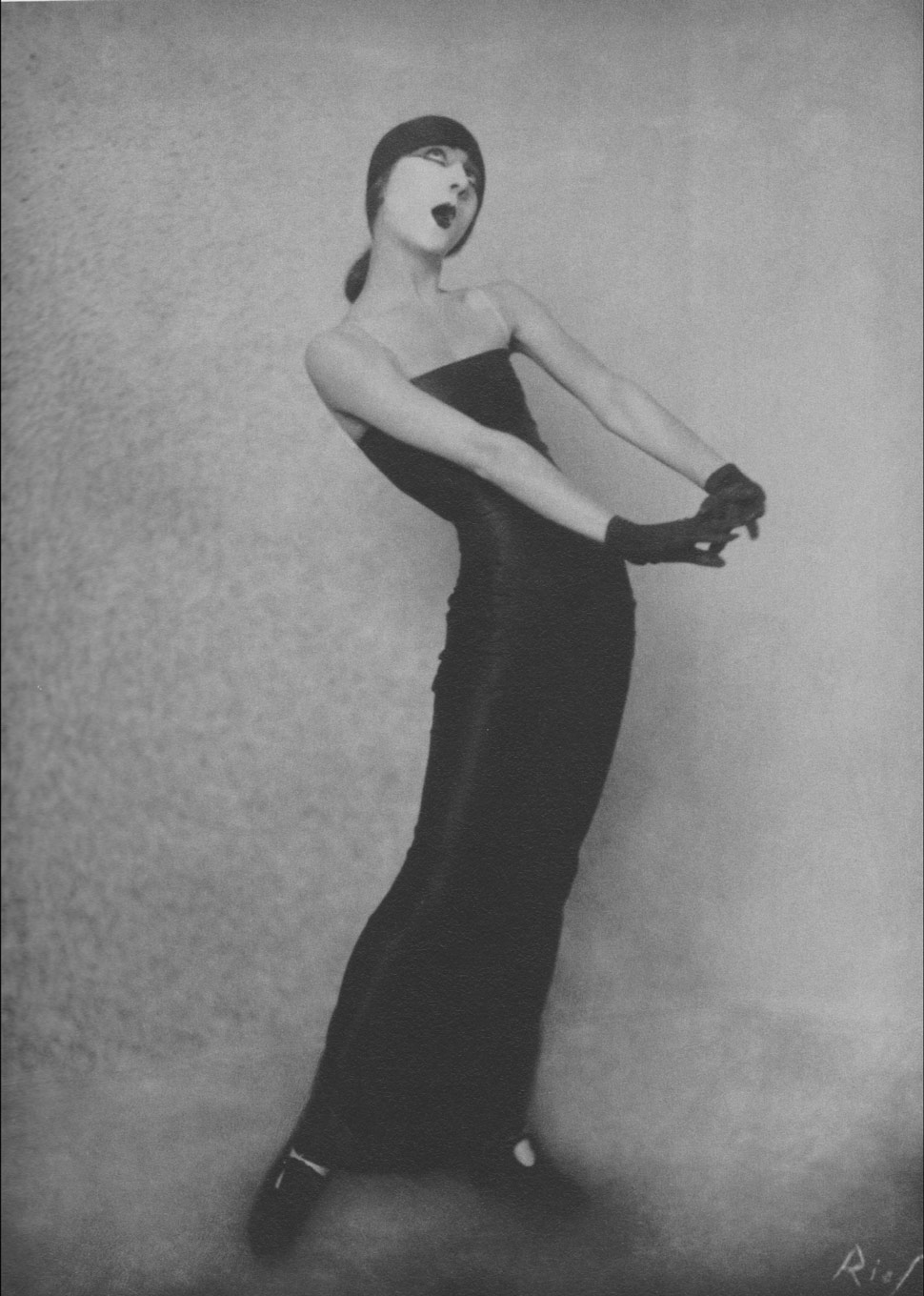

Women played a particularly pivotal role in the world of cabaret, especially after 1920, when they were given the right to vote. They were an integral part of artistic collaborative teams, both professionally and personally. “Some were even married, as was the case with Friedrich Hollaender and his wife Blandine Ebinger, or lyricist Marcellus Schiffer and his wife Margo Lion. Many composers and lyricists wrote specific songs for specific performers.” Female cabaret vocalists rose quickly in Weimar cabaret in song genres that ranged from prostitute songs, to ballads, to parodies and satirical songs. In the performance practices they were at once “diseuses” (ones who spoke more than sang) and “chanteuses” (ones who sang more than spoke). “Female artists in particular fought to maintain this image of the newly liberated German woman,” says Adi, “and no-where was this ‘not-so-quiet’ trend felt more profoundly than on the stages of Berlin cabarets.”

Reviving lost art

The rise of Nazism made it increasingly difficult for many of these cabarets, and any artists that were Jewish or associated with Jews. “Jewish artists made up more than half of the performing body of Weimar cabaret,” says Adi, “and since Hitler’s regime forbade any non-Aryan content in the arts, I believe one could say that the growth of German culture was stunted…quite literally…overnight.”

“An unspeakable amount [was lost],” says Adi. “Hundreds of books, recordings, films and musical manuscripts were destroyed by the Nazis.” Many cabaret artists fled or were killed, and “a pivotal art movement came to a grinding halt.”

In her own way, Adi is breathing life into some of this lost music, and reviving the memory of its artists. “One night I had a dream in which all of these performers came to me and whispered: “Vergesst uns nicht!” (“Don’t forget us!”). This has become my ‘mantra’ - let us not forget the great players and the works that were produced by this utterly unique art form. I told my wife – pianist, lawyer, and recent PhD recipient Linda Ippolito – about this dream and she challenged me to take my dream further by applying to the Faculty of Music to continue my research.”

Adi is one to put research into practice. In February, she’ll co-host the next instalment of the new VOCALIS series, a concert project curated by Wendy Nielsen; no doubt she’ll add some singing of her own to her hosting duties. Adi performs regularly at Toronto’s Jazz Bistro, and she’ll sing from the notoriously delicious Kurt Weill Songbook in April 2016. On top of performing, Adi is composing a cabaret song-cycle, entitled KOLIBRI. To hold you over until her live performances, here’s a taste of Weimar cabaret, Blandine Ebinger singing Friedrich Holländer’s 1927 “Die Hysterische Ziege” (“The hysterical bitch”). You can read the original text below, plus an English translation by Adi Braun herself.

ICH BIN DIE HYSTERISCHE ZIEGE (Friedrich Hollaender, Blandine Ebinger; 1927) Ich hab’ schon sieben Maenner in’s kuehle Grab gebracht Erst hab’ Ich mir mit Henna die Haare rot gemacht Dann woll’t Ich auch ‘mal blonde, dann war’n sie wieder gruen Ich bin die hy-ster-siche Ziege von ganz Berlin Ich Weiss nicht was Ich moechte, Ich moecht’ nicht was ich weiss Im Sommer ist mir frostig, im Winter ist mir heiss Mensch bin Ich hysterisch…….. Eben lach’ Ich, bums da wein’ Ich und dann schrei ich wie am Spiess Ich find’s albern, ich find’s reizend, bitte sehr wie finden Sie’s? Ich bin krank, Ich bin gesund, ‘mal hab Ich das mal hab’ Ich dies Ich find’s albern, ich find’s reizend, bitte sehr wie finden Sie’s? Ich liebe kleine Kinder wenn sie von andern sind Um Himmel’s Will’n kein eig’nes, denn schrecklich ist so’n Kind Will das man klapper/klappert, dann will es wieder nicht Dann hat es sich gesappert, dass waere was fuer mich Es weiss nicht was es moechte am Tage und bei Nacht Eh man was boeses daechte, hat es sich nass gemacht Mensch ist das hysterisch…… Eben lacht es doch da weint es und schon schreit es wie am Spiess Ich find’s albern, ich find’s reizend, bitte sehr wie finden Sie’s? ‘Mal ist’s krank ‘mal ist’s gesund ‘mal hat es das ‘mal hat es dies Ich find’s albern, ich find’s reizend, bitte sehr wie finden Sie’s? I AM A (THE) HYSTERICAL BITCH (Friedrich Hollaender, Blandine Ebinger; 1927) English Translation: Adi Braun, 2014 I’ve already managed to bring seven men to the cool grave First I coloured my hair red with henna But then I wanted to be blond but then again it turned green I am the hysterical “bitch” (goat) from Berlin I don’t know what I like – I don’t like what I know In summer I am freezing and in winter I am hot. God – I am hysterical Just now I laugh…then I am crying bloody murder I think it’s funny, I think it’s charming…but what do you think? I am sick, I am healthy…sometimes I have this or that I think it’s funny, I think it’s charming…but what do you think? I love little children, if they are other people’s kids But oh dear God not one of my own, because a child is just a terrible thing! First it wants you to play with it and then again not Then it has spit up food… well that would be just dandy! It never knows what it wants – by day or by night And just before one has dark thoughts…it has wet itself! God – isn’t that hysterical! One minute ago it laughed, now it’s crying and then it’s screaming bloody murder I think it’s funny, I think it’s charming…but what do you think? Sometimes it’s sick, sometimes it’s healthy…sometimes it has this or that I think it’s funny, I think it’s charming…but what do you think?

Comments