The follies of modernization: Oedipus Rex & Iolanta

ReviewConvention is convention. No matter the parameters, adherence to convention can make for dull theater. The mainstream operatic paradigm has common elements that while once modern or “stylized” have become pat: naturalistic acting broadened to accommodate music, slow motion or highly choreographed chorus pantomimes, projections (always projections), an added plot twist or shocking tableau to spruce up old material. There’s nothing inherently wrong with any of these staging tricks, but when they’re employed in an obligatory way, they risk sterilizing a piece’s more adventurous intentions.

Director Lydia Steier’s attractive new production of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex, double-billed with Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta for Oper Frankfurt, follows a conventionally modernistic approach that conflicts with the composer’s more figurative conception. Stravinsky imagined Oedipus as a “still life” in which “The people in the play relate to each other not by gestures, but by words. They do not turn to listen to each other’s speeches, but address themselves directly to the audience.” By eschewing broad naturalism, he hoped to focus not on the characters’ inner lives but on the inertia of fate itself, which he believed macro musical structures could characterize uniquely well. Steier’s naturalistic approach deliberately homes in on Oedipus’ psyche but to what end? Has she devised a more palatable way into a challenging piece or has she diluted the piece’s peculiarities that make it extraordinary?

At the opera’s outset, a plague threatens to rout the population of Thebes (played by Oper Frankfurt’s tremendous male chorus), who pleads for King Oedipus’ aid. Gaunt, nearly nude, and covered with boils, a man is dragged into the forum as a literal representation of the city’s ills. Oedipus (gamely sung by Peter Marsh), however, is a stick to the agenda kind of guy. Largely ignoring the hideous sight at this feet, he lays out his credentials as Thebes’ prospective savior. He communicates in sustained planar whines that grow higher and harsher the longer he wails. He’s the kind of politician who bludgeons his constituency with dogged persistence to compensate for lack of charm. At this point, the Thebans will take what they can get.

Soon Creon (Gary Griffiths) arrives ecstatically with good news from the oracle: the murderer of the previous king, Laius, is in Thebes. If they can find and banish him, the plague will end. Sweet news to the ears of King Oedipus.

As the investigation snakes through a series of witnesses, Oedipus’ psyche unravels. An omnidirectional, childlike voice whispers his fate to him moments before it’s enacted – a clever way to repurpose Jean Cocteau’s added spoken narration, whose pomposity Stravinsky himself retrospectively decried. Layer by layer, Oedipus’ misdeeds are revealed. It becomes clear that Oedipus unwittingly murdered Laius at the crossroads, and that Oedipus, a foundling, is actually the progeny of Laius and Jocasta (sung with swagger by the richly voiced Tanja Ariane Baumgartner), Oedipus’ pregnant wife.

Guilty beyond a doubt, Oedipus stabs his eyes out. As he staggers back into the forum, blood dripping from his sockets, a messenger arrives with a second fateful blow: Jocasta is dead. The stage rotates to reveal Jocasta, hanging from a noose. Her nurses, blood smattered, unable to save the unborn baby, lay helplessly at her feet.

Dramatic, right? But not what the composer imagined. Stravinsky said about Oedipus’ final moments, “His self-violence is described, but not enacted: he should not move. Those directors who whisk him offstage and then bring him back realistically staggering in an unreal, stylized, costume have understood nothing of my music.”

Can a modern audience tolerate abstraction? Steier seems to think not, judging by the amount of eye-roll inducing visual hand-holding. For example, in case you forgot that Oedipus is intimate with his mom, projections alternate from baby Oedipus suckling a breast to adult Oedipus doing the same, while real-time Oedipus sucks the queen’s breast through her dress. Point taken.

That said, the force of the music comes through. The score builds cunningly over the course of the short drama, lulling the audience into moral ambivalence. Starting with the lilting, sumptuous oompah that introduces Jocasta’s aria, which maestro Sebastian Weigle and his orchestra played with queasy, dizzying beauty, the score blurs the audience’s allegiances. Queen Jocasta winds her treacherous words into urgently compelling figures, and the male chorus’ definitive rhythm’s convincingly advocate for their specious accusations. Dramatic irony be damned, the moment the audience gets comfortable, Stravinsky’s wallops it with a towering, harmonic tidal wave that seems to warn against complacency.

Stravinsky said that “The rhythms are the principal source of dramatic tension and a major element of the dramatic method,” and he’s right. Their pounding seems to lodge in one’s bloodstream, still knocking away after the curtain drops, as if to say that fate, steady and unceasing, will catch up to you whether you like it or not.

Tchaikovsky’s final opera, Iolanta, based on a Danish verse drama popular at the time, in a way begins where Oedipus left off. Its protagonist is both blind and ensnared by fraternal difficulties. The young princess Iolanta’s father, the powerful King René, has made sure his daughter remains ignorant of her disability by confining her to a meticulously controlled alternate reality that he’s created.

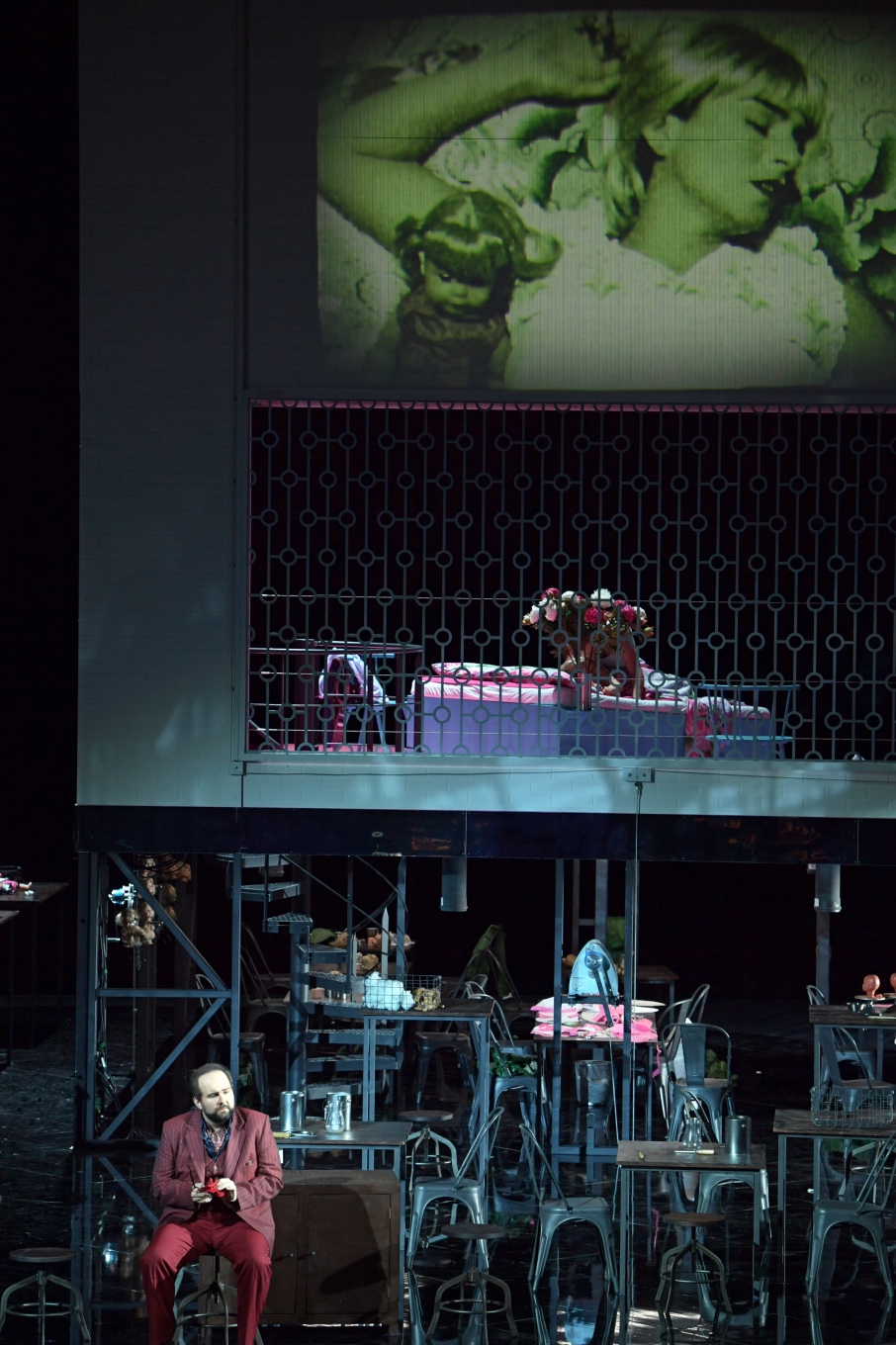

Steier and her team have built an achingly immersive split-level environment. Downstairs, a sprawling factory floor bustles with activity. Assembly line workers manufactures dolls, while identically dressed servants prepare for the evening’s chores. Upstairs in Iolanta’s bedroom, King René, and his daughter’s three principle caretakers maintain an illusion of serenity replete with fresh cut flowers, and hundreds of identical dolls, dressed just like the young princess, lining the walls.

Today has been a hard day for Iolanta. A nagging emptiness plagues her. Only her favorite childhood lullaby will settle her nerves. At her request (or more accurately her father’s command), her three principle nannies spin sumptuous melodies, lush with harmony and delicate counterpoint, while a fully choreographed backup choir sways in unison. Layered melodies expand and contract, gently easing Iolanta to sleep. The production number ends and René heaves a sigh of relief. Another day done with his grand illusion intact.

But that’s all about to change. Robert, Duke of Burgundy, who is betrothed to Iolanta, and his sidekick Vaudémont, unwittingly find themselves in the factory after hours. They’re unaware this is Iolanta’s home. Rumor has it she’s been holed up in a Spanish convent for years. Robert isn’t interested in the princess anyway. He’s in love with Countess Mathilde and boisterously sings about it.

As the boys holler downstairs, King René makes his way into Iolanta’s bedroom. Watching her sleep, he carefully sets down his gun, methodically undresses to his underwear, climbs into Iolanta’s bed, and rapes her. Certainly not in the libretto, this is a disconcerting addition.

It’s a crass move to co-opt sexual assault as a means to artificially raise an opera’s stakes. It also causes serious dramaturgical issues. By screwing around with the plot, the director has given herself the irreconcilable task of manufacturing staging that respects the repercussions of Iolanta’s assault, while spinning an idyllic, fairytale love story, with a libretto that only supports the latter.

After the assault, Robert and Vaudémont enter Iolanta’s room. Vaudémont is entranced by what he sees: a teenage girl, dressed like a child, passed out, in a room filled with dolls dressed exactly like her. If this spells love for Vaudémont, he’s a pervert, or worse, a sexual criminal. That’s a problem since the rest of the story depends on believing, in good faith, that Vaudémont and Iolanta develop a love so true that it cures Iolanta’s blindness. Their relationship’s plausibility never manifests.

King René’s character is flattened by his horrific deed. In the original story, the king smothers Iolanta, but the extent to which he orients his life towards protecting her is at once sickening and touching. That messy ambiguity plays out over course of the piece, the audience never quite sure how to feel about his intentions. That’s drama. If you polarize the audience against the character by turning him into a representation of pure evil, the mystery evaporates, and with it, the possibility of dramatic tension.

Still, there’s a lot of good in this production, including some first rate singing. Asmik Grigorian’s (Iolanta) ruby hued voice has tremendous bloom in its upper register, which Tchaikovsky’s score exploits again and again. Grigorian paces the role deliberately; each climax surpasses the last. At Iolanta’s true climax at the end of the extended love duet, Grigorian unleashes a thrilling, sprawling, hair-raising high note that seems to engulf every molecule in the theater. Grigorian’s bold, mature sound empowers her Iolanta, transcending the character’s horrific victimization.

Robert Pomakov, as King René, also stands out. Few opera singers calibrate their performances so deftly. Pomakov’s every movement is deliberate, goal oriented, and revealing. His René exudes a placid, profound sadness. Pomakov’s voice is rich, sizeable, yet facile. Its grace contrasts poignantly with his character’s villainous mien.

The supporting performances are also strong. Andreas Bauer, who never seems to have a night off (he had just finished a run of Rusalka that overlapped with Zauberflöte), maneuvers through the Moorish doctor Ibn-Hakia’s treacherously pitched arias without strain. The three head maids, played by Judita Nagyová (Martha), Elizabeth Reiter (Brigitta), and Nina Tarandek (Laura), evince depth and beauty in their sublime lullaby. Both Gary Griffiths (Robert) and AJ Glueckert (Count Vaudémont) tighten in their upper ranges but make it through the evening with their voices intact.

The consummate cast and creative team delivers a memorable evening of opera, despite the erroneous plot element that threatens to derail the piece. Taken as a pair, Oedipus and Iolanta showcase two Russian-born masters, from two different eras, with two entirely different compositional approaches.

Oedipus Rex and Iolanta run at Oper Frankfurt through December 1. For details and ticket information, click here.

Comments