Orpheus & Eurydice in the hands of a theatrical genius

ReviewToo often, opera directors are referred to as “theatrical geniuses”, but the success of their productions are almost always a collaboration with great designers and, in the case of operas with ballet passages, great choreographers. With Orpheus and Eurydice, however, which just began its run at LA Opera, “theatrical genius” can justifiably describe the work of one man working alone - John Neumeier. He is not only the director of this production, but also the choreographer, set designer, costume designer and lighting designer. Talk about a single vision. And what a visionary.

Though he has a decades-long, international reputation for his ballets, Mr. Neumeier’s ingenious and beautiful choreography is only part of the story, or rather “his” story. Writers are supposed to write what they know; in this case, Mr. Neumeier directs what he knows. This is the famous opera written by Gluck in 1774, but it’s no longer the travel and travail of a musician. In Mr. Neumeier’s concept, Orpheus is now a choreographer. And while we’ve seen so many directors who try to thrust themselves in between the work and the audience, in this case, the director’s conceit enhances our understanding of how Orpheus (and his art) are infinitely transformed.

As written by Gluck, there are only three principal singers in the opera - Orpheus, Amour and Eurydice. In most productions, the chorus is an integral part of the staging, not only in the choral sections but during the long instrumental passages. But here, the always-glorious LA Opera chorus is only seen at the curtain call. They have been replaced with the constant presence of dancers. Everything that is not an aria, duet or trio, has been turned into a spectacular Neumeier ballet (performed by members of The Joffrey Ballet, one of the crown jewels of American dance.)

The libretto is based on the famous Greek myth of Orpheus who enters death’s kingdom (the underworld) in order to find his beloved but recently deceased wife Eurydice, and bring her back to the world of the living. That’s not something ever allowed by the gods, but they make an exception in the case of Orpheus because his music (or in this case his choreography) has always pleased them. The gods are never known to be fair to mortals, however, and there’s an important caveat: Orpheus cannot look at Eurydice as he rescues her, otherwise the deal is off. (That’s a great set-up for one heck of a duet between the leads when they are finally reunited. We aren’t disappointed.)

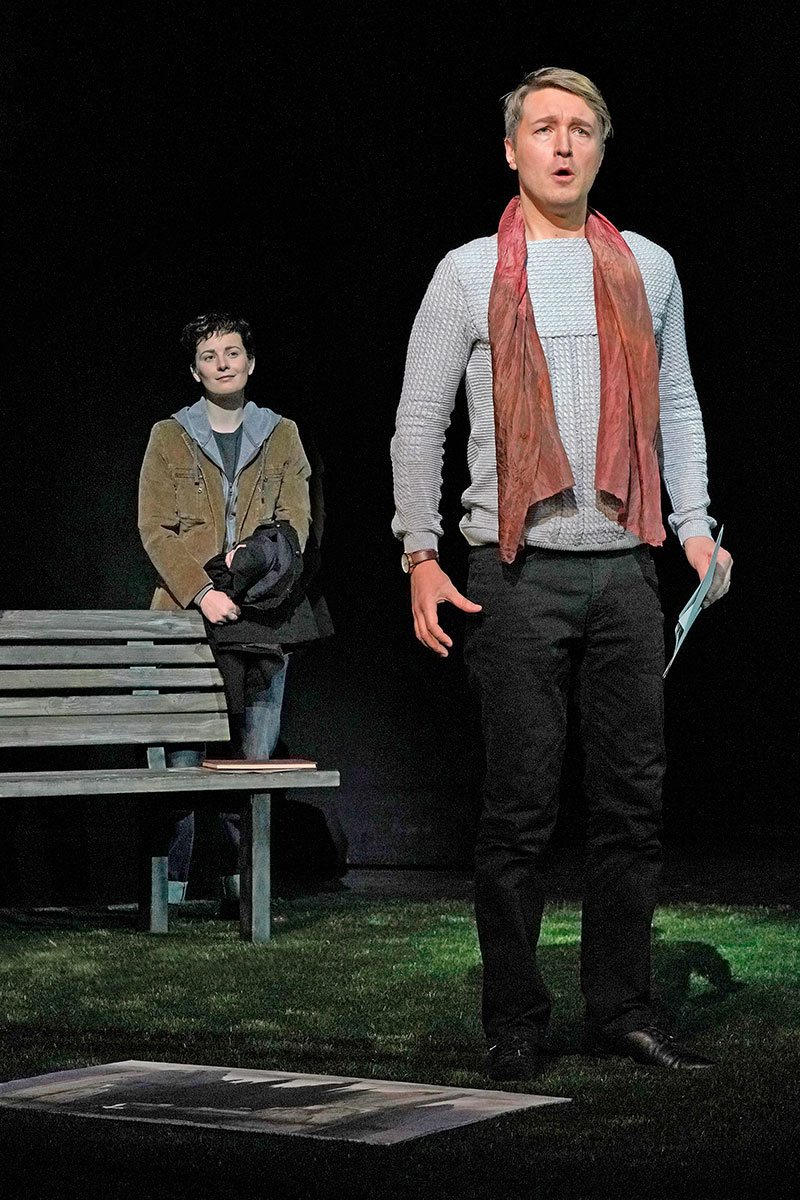

Neumeier’s take begins with Orpheus trying to create a new dance with his ballet company. The members are all over the place trying different moves - some in small groups, some in pairs. Orpheus is clearly looking for inspiration. We’ve been introduced to a painting of his set design on an easel. But his work on the piece that will appear in front of that backdrop is only just beginning. Eurydice is the prima ballerina, and right after we are introduced to her, she has a fight with Orpheus and leaves the rehearsal in anger. And this all happens during the overture. Blackout.

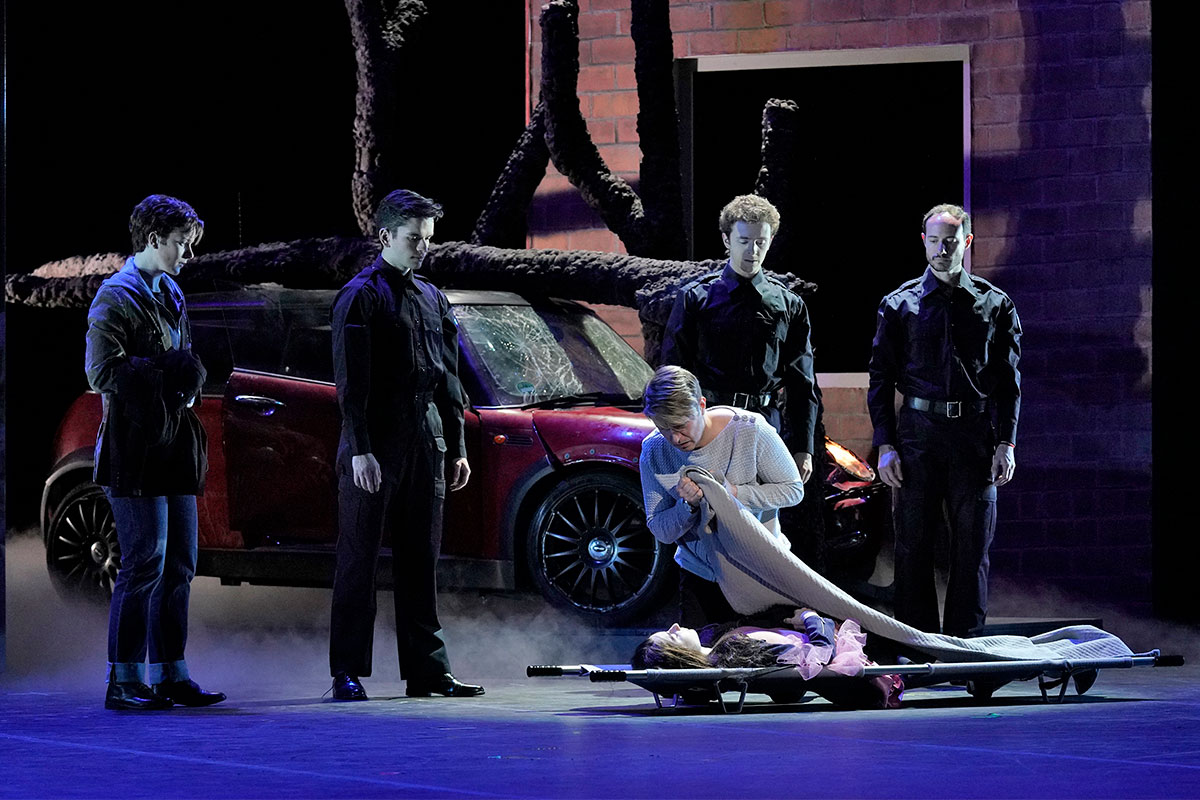

When the lights come up, we see Eurydice dead on the ground. Off to the side we see that she has crashed her mini-Cooper into a saguaro cactus in the middle of the night. In the hands of anyone else this would be a potentially silly nod to modernism, but the scene is haunting, thanks to the minimal lighting that streams from the headlights through the steam of the broken engine. A tall, black, and spooky shadow of the cactus appears on a wall. The ballet company, now dressed in black, do their dance of mourning over the loss of their colleague as the chorus sings hauntingly unseen in the background. This is a perfect example of how Neumeier is able to blend his expertise in staging, dance, lighting and costumes - it all comes together to enhance the sadness and mystery found in the music that Gluck has written for the beginning of the opera.

Gluck’s music has been called the bridge between Handel and Mozart and you can certainly hear how Gluck inspired Mozart. (Listen closely and you’ll catch what would become “Non più andrai” in The Marriage of Figaro.) The music is endlessly lyrical, and, in the style of the time, subdued even in its most dramatic moments. This doesn’t prevent James Conlon from conducting the always spot-on LA Opera orchestra with a fevered passion that allows him to elicit the most from the score…and then some.

Gluck was revolutionary, in that his music propelled the drama of the story. Ahead of his time, he was against stopping the action to allow self-indulgent singers to engage in vocal calisthenics. He does break this rule at the end of Act I, however, where Orpheus (sung by Maxim Mironov) has an aria filled with ever-climbing, very challenging Baroque trills. It’s a great moment, and it’s Mironov’s greatest.

Although his voice lacks heft, he has bel canto chops and can float up to impossibly high notes with ease. The role can be sung by a more powerful tenor, but it’s often sung by a mezzo-soprano or even a counter-tenor, so we don’t feel anything is missing. Neumeier has also directed Mironov to give a moving, subtle and modern performance, which fits neatly into the production’s present-day milieu.

Lisette Oropesa as Eurydice is lovely, both vocally and in her graceful ghost-like paces through the land of the dead. Dressed in a beautiful white wedding gown, we’re riveted to her presence whenever she’s on stage. Liv Redpath as Amour, is a full-fledged star now at LA Opera, and rightly so. This reviewer has enjoyed three of her tremendous performances this season. (The others: Frasquita in Carmen and Anna in Nabucco.)

Thanks to the talents of the three leads, the trio sung by Mr. Mironov, Ms. Oropesa and Ms. Redpath before the finale of the opera, proves to be a show-stopping “11 o’clock Number.”

If this whole directing thing doesn’t work out, Mr. Neumeier could make a fortune as an in-demand set and/or lighting designer. He expertly uses translucent mirrors, which not only reflect the performers who are standing in front of them, but also reveal the performers who are behind (thanks to lighting tricks from Mr. Neumeier’s lighting designer, Mr. Neumeier.)

Orpheus enters Hades by walking through the mirrors (like Alice?) and when the mirrors are turned around, we’re now looking at a giant version of the painting that we saw on the easel during the overture. To our surprise, the hands, feet and faces of the Furies burst through the painting, grabbing at Orpheus, trying to pull him down into their world.

The underworld itself is represented by three spinning cubes, the interiors of which are composed of multiple doorways. Here, there are also mirrors. And when the cubes are turned at the appropriate moments (by dancers, of course) multiple reflections of the doorways and characters are created. We even sometimes catch a glimpse of multiple James Conlons in the pit, too.

Mr. Neumeier is also adept at small but evocative touches. The boat that brought Orpheus across the river Styx, hangs upside down above the action in Act II, as if it had spilled Orpheus into the scene. When Orpheus is in his bedroom at the top of the show (and later again at the end) he is boxed in with black, lit only by a Rembrandt-like illumination from an open window. Only the muse of love will free Orpheus from this box, Mr. Neumeier seems to be saying.

At the end of Gluck’s opera, Eurydice is brought back to life by the gods but Mr. Neumeier has chosen to not take this literally. Though the lyrics tell us that love triumphs over all (“l’amour triomphe”), Eurydice and Orpheus remain in separate parts of the stage. She is off to one side while he sits in a row of theatre seats, watching his dancers. She is alive only in his heart - and in his art - as an inspiration for the ballet he is finally able to stage, and which ends the evening in a glorious finale. Mr. Neumeier has found more than a love story. Orpheus is a story of transformation. His journey is not to hell and back, but begins and ends via a seamless and extremely imaginative loop.

Orpheus and Eurydice is onstage at LA Opera through March 25.

Comments