Opera adapts a medium more adept at adapting

ReviewAs much flack as Hollywood gets for retooling old properties, mainstream contemporary opera could be similarly chided for borrowing from film. Heggie’s hit Dead Man Walking was a star studded movie, itself adapted from a book. He also recently redid It’s a Wonderful Life. I doubt Cold Mountain (Jennifer Higdon) and Brokeback Mountain (Charles Wuorinen) would have been mounted with such fanfare had the movies not achieved critical success. Kevin Puts’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Silent Night is based on the screenplay for Joyeux Noël, and Thomas Adés’ Exterminating Angel, Missy Mazzoli’s Breaking the Waves, and Nico Muhly’s Marnie all adapt works by revered art film directors. How does Yuval Sharon’s new Oper Frankfurt production of Olga Neuwirth’s 2003 adaptation of David Lynch’s classic film Lost Highway fit into the movie-opera paradigm?

The production design is daring with the playing area split in half horizontally, a full size stage built above the usual one. A green screen environment spans the lower level and an animated rendering of the green screen stretches across the top. A lot about the setting is anachronistic though, for example the clothes are retro but the architecture is modern, there are both iPads and flip phones, and though it’s 2018 the graphics look like a slow motion version of Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.

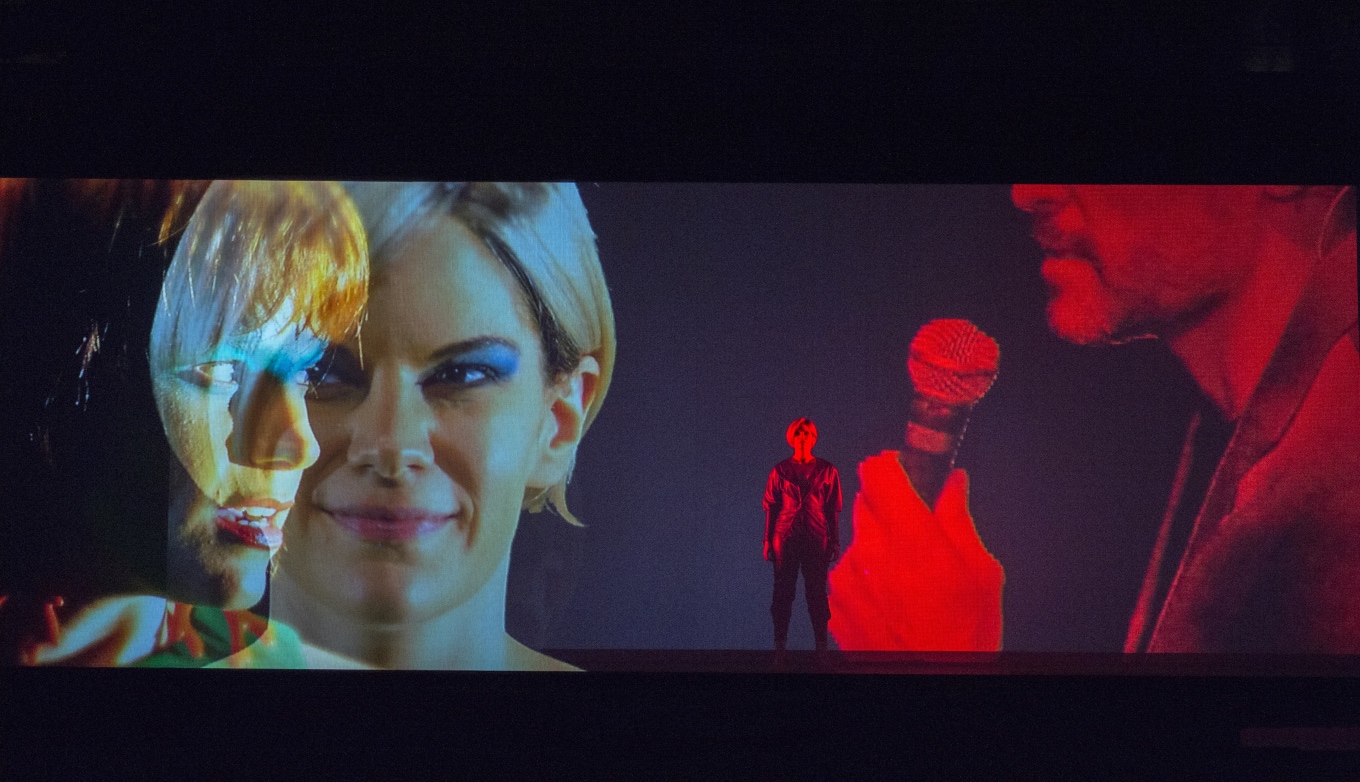

The green screen itself, a nod to movie making, has some loose symbolic value but is better in theory than practice. The show’s protagonist, Fred (Jeff Burrell), is isolated and confused. His wife Renee (Elizabeth Reiter) seems involved in shady activities of which he knows little. Now mysteriously intimate tapes of him and Renee have shown up on their doorstep. In the green screen environment, Fred is literally isolated. He mostly interacts with animated figures on the platform above him. Often Mr. Burrell’s body angles and movements must correspond to animations that he can’t see which dampens his spontaneity as an actor.

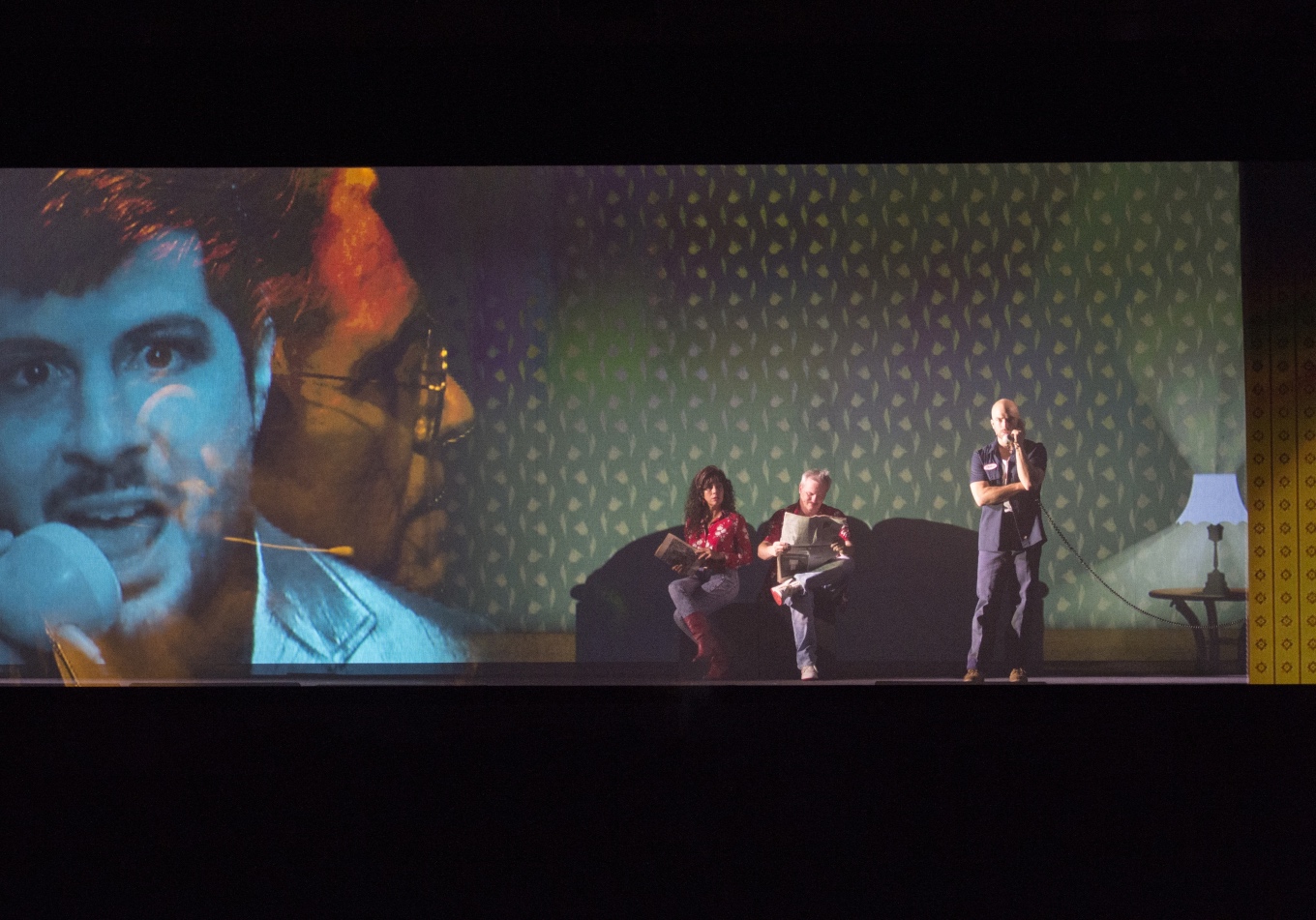

A third tape arrives. Creeped out, Fred watches the tape alone only to see an image of his wife splayed out, covered in blood on their bedroom floor. Fred himself appears in the video, also blood stained, and looms over his wife’s body. Evidently he’s murdered her, at least according to the video, and he’s quickly convicted and sentenced to death. On death row, Fred transforms into Pete (John Brancy), a naive young man who seems entirely unrelated to Fred. The transformation takes place on the upper platform with strobing animations blurring the line between the two characters until Pete has replaced Fred and lies fetal and mute in the shadows of his cell. From then on, the opera takes place mostly on the upper level, and the set functions more like a traditional stage.

Despite its unique design, this production mimics Lynch’s movie to the point that the shadow of the original material dwarfs anything the opera might have to say. The film’s characters speak with an off-kilter timing and a subtle affectation that risks but never quite crosses over into melodrama. To approximate that effect, the opera’s actors flatten their voices into an overly “placed” monotone. In what world do people talk like this? Add to that a libretto that cherry-picks the screenplay’s most peculiar lines while cutting the quotidian ones and what’s left is an opera whose reality never solidifies.

Then there were some downright strange choices. The Mystery Man (sung with understated virtuosity by Rupert Enticknap) was costumed in a gold-fringed Elvis suit and made up indiscernibly. The Mystery Man is the piece’s surprise antagonist, responsible for the story’s underlying terror. The score casts a countertenor, which might have felt fresh in 2003, but now seems like a cliché grab at weirdness. Another disappointing choice was that Pete’s father, in the movie played by Gary Busey, looked like Gary Busey, was costumed like Gary Busey’s character, and behaved like a caricature of Gary Busey, idiosyncratic but without humanity.

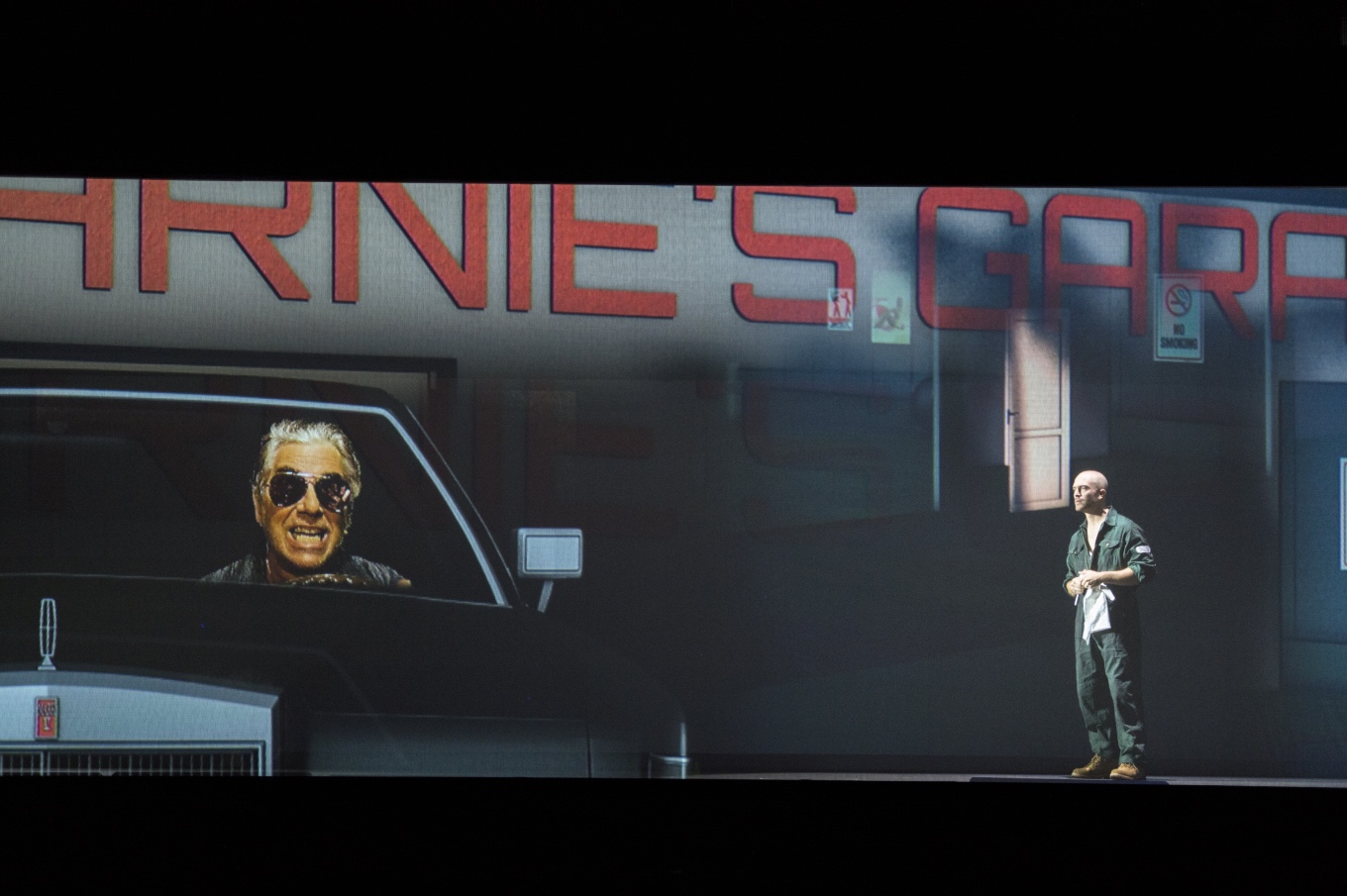

The opera’s libretto taints some of the movie’s most beloved scenes, like when the porno kingpin Mr. Eddy (David Moss) dresses down and mauls a tailgater on Mulholland drive. Any Angeleno would recognize the argument Eddy uses to justify his violence: that you must maintain a specific number of car lengths between you and the car in front of you in order to stay safe at high speeds. Tellingly, Mr. Eddy draws Pete into the conversation, appealing to his auto expertise to lure him into tacit complicity. But in the opera, Eddy’s rant is moved into the auto shop where he rants at a random guy puffing away near a “No Smoking” sign. The speech becomes a dull non-sequitur that serves the character broadly but fall short of the artful layering the screenplay achieves.

For an opera, the score doesn’t have much singing. Mr. Eddy’s part is the most unique, full of guttural throat clicks, pops, screams, and burps. At one point he babbles like a tape on fast forward, an unexpectedly thrilling effect live. The character comes off more comic than scary, but who cares with such entertaining music.

Pete is the real protagonist of the show, and John Brancy’s voice had the warm cushioning that’s served him so well as a lieder singer and has kept his voice pristinely healthy despite rigorous seasons of wide-ranging repertoire. Even his falsetto bloomed immaculately. He’s a better singing actor than straight actor. Without music he seemed distracted by the sound of his own voice. But he’s well cast. His innate naiveté contrasts with his athletic build which serves Pete’s tough guy facade. Brancy’s opposite, Elizabeth Reiter as Alice and Renee, made sense of treacherous melodic contours and roared at the top of her range.

The opera’s sonic world as a whole is consistent, immediately discernible, and immersive with intricate electronic tapestries undergirding the entire piece. Now new music folks widely recognize Neuwirth as an electronics expert and this 15 year-old composition demonstrates how long she’s had a superior control over the medium. Ultimately though, the piece doesn’t add much to its source material’s story. With the amount of acclaimed work Ms. Neuwirth has created since 2003 and her sterling reputation as an innovator, it seems reasonable for her to shelf Lost Highway for good.

Comments