In review: Tristan and Isolde at ENO

ReviewDaniel Kramer’s is the first new production of Tristan and Isolde at English National Opera in 20 years, and after his recent appointment as ENO Artistic Director, his Tristan seemed like an unofficial introduction to his aesthetic.

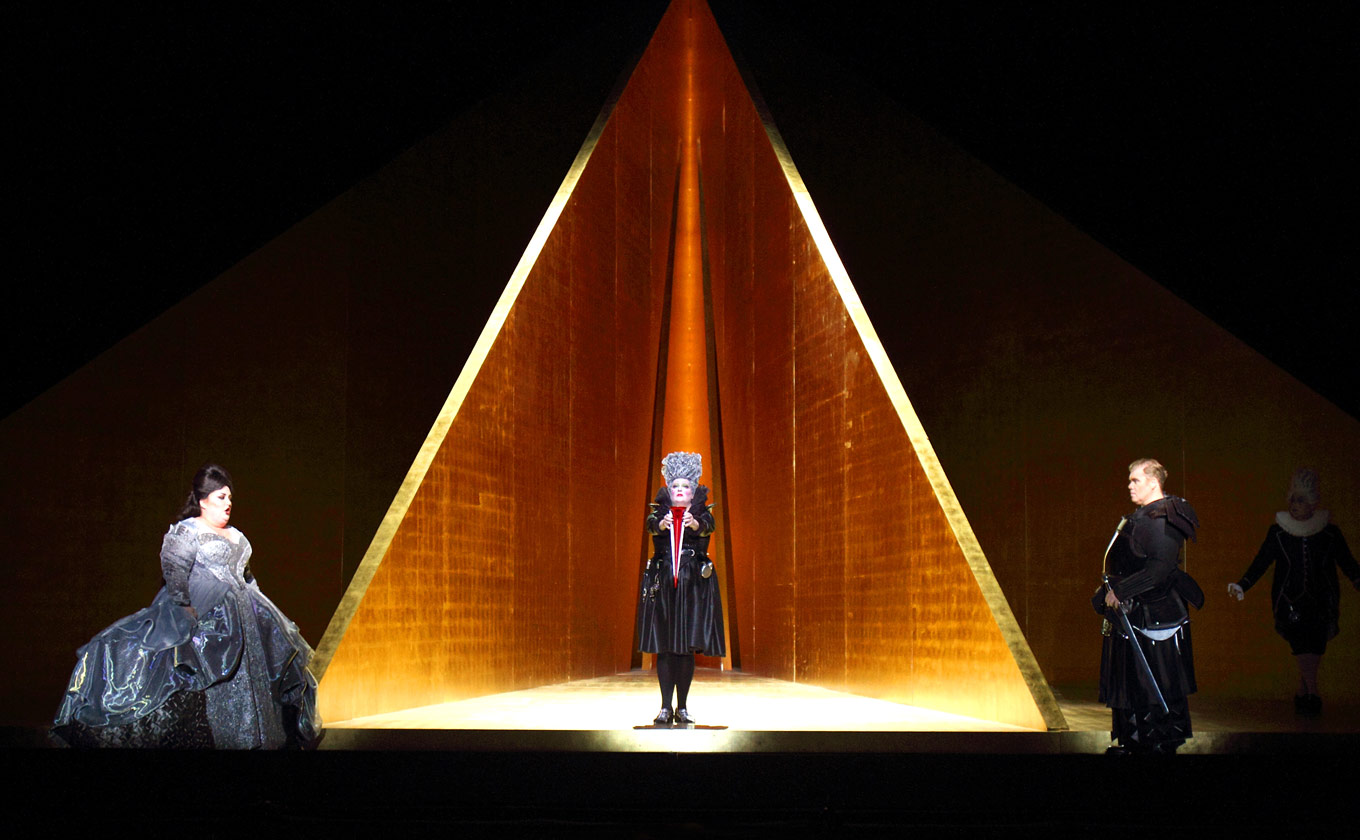

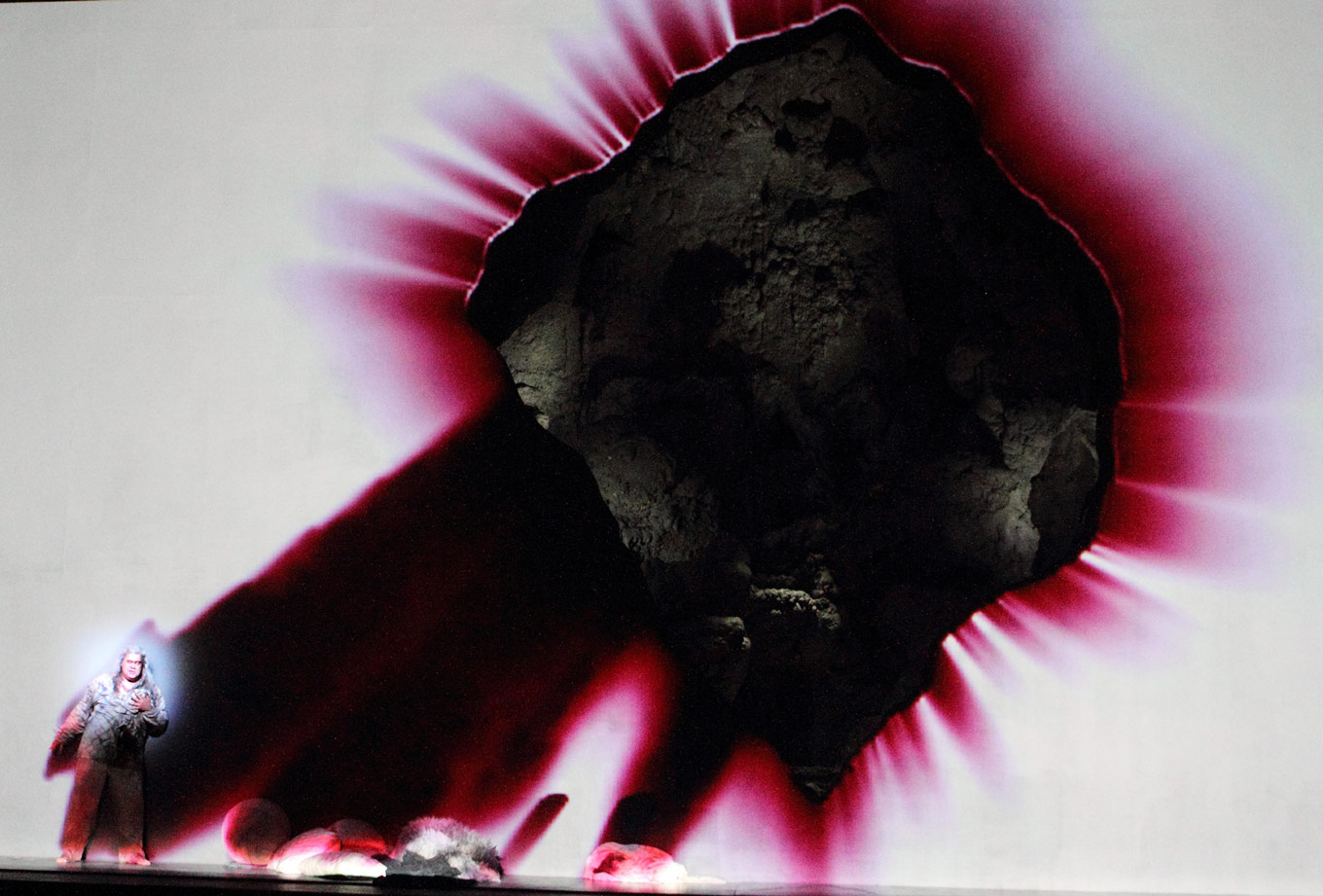

The production is visually arresting, with brilliant design by Anish Kapoor (sets), Christina Cinnungham (costumes), Paul Anderson (lighting), and Frieder Weiss (video). Each act featured an exaggerated, supernatural imagination of the old and still timeless world of Tristan and Isolde.

Tristan’s ship was full of looming angles and barriers, allowing for beautiful symmetry of the two would-be lovers and their respective servants. Act II seemed an otherworldly spot for Tristan and Isolde’s nocturnal tryst; it looked like its own planet, or perhaps the very center of the earth, in either case clearly underlining the singular, primordial ur-love that this couple embodies. Act III was bleak, harsh white against thick black, evolving only to blood red and a charred vista of dead rock, where Isolde and Tristan reunite in life for the last time.

As stunning as each tableau is, there was a through-line that stayed evasive. Each scene seemed to have its own aesthetic, yet without enough to connect this very large story. Tristan and Isolde seemed to live long ago, and also in a futuristic world, with the addition of time-specific hospital beds and a crowd of surgeons accompanying King Marke’s entrance.

It’s not a story that really asks for a literal time and place, this production felt more like a series of scenes, rather than a completed story arc; perhaps the disconnect came from how the imagery and imagination were so exaggerated, that it became difficult to “descend” back into the more practical moments of the story. The design of the production is delicious, and it would be a shame to dampen it for the sake of the moments of crowd scenes; perhaps Kramer was after a sense of deflation akin to what Tristan and Isolde feel when their alone time is interrupted.

Stuart Skelton was a strong Tristan, manly and down-to-earth. His monologues in act III belied some fatigue, and as the tessitura stayed high, Skelton lost some of the grounding in his sound; he never faltered as an actor, though, and he was magnetic to watch. Heidi Melton made her ENO debut as Isolde, and she made beautiful work of the English-translated libretto. Her sound was touching and full of dramatic choices; at times, her full body didn’t feel committed to the sound, and her more ecstatic moments grew wild.

Kramer kept the pair apart, more than Wagner seemed to say with his score; the music, lusciously delivered by maestro Edward Gardner, was what convinced us of their connection, and it didn’t feel matched by any onstage chemistry. Perhaps Kramer was going for a more chaste love, but Wagner does not.

Matthew Rose seemed a human King Marke, more of a man than a figure. He sang with a bright, immediate sound, yet there was a habit of starting each note with a straight tone. At times that habit affected his intonation, making some of Wagner’s juicier key changes a bit obscured.

Karen Cargill was wonderful as Brangäne, Isolde’s servant. She sang with power and brightness that seemed to ooze loyalty to her Lady. There was personality in her sound, helped by her almost cartoon-like portrayal and swift, uppity motions.

It was Craig Colclough’s Kurwenal that stole the show. A role debut for him, his enormous sound felt wonderfully offensive in act I, and act III seemed to belong to him. His voice is a thrilling, bright bass-baritone, and he was all at once heartbreaking and a much-needed source of comic relief.

We’re still getting used to the strictly English-language productions at ENO. Translating German to English isn’t as jarring as Italian or French, and in his translation of Tristan and Isolde the late Andrew Porter also preserved some of the original libretto’s rhyme schemes. Generally, one can either get a translation that’s very accurate, or a translation that rhymes in both languages. The jury is likely out about whether or not poetic rhythm is more important than textual accuracy, but we would have prioritized the latter.

Tristan and Isolde runs until July 9th at the London Coliseum. For details, click here.

Comments