From Don Juan to #UncleJohn

EditorialDon Juan. Love him or hate him, he’s been around for at least 400 years. Why? Because he’s a juicy character with which we’ve all got something in common. Everyone struggles with moderation in their lives; food, drink, and sex have forever played a role in our personal conflicts with desire and will-power. If you’re mysteriously immune to the temptations of the Big Three, you’re bound to be lured by something else. Or, you’re a robot.

The first written account of the Don Juan story is thought to be the play by Tirso de Molina, written in 1630 and set in the 14th century. It’s entitled El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest). We meet the servant, Catalinón, who exasperatedly cleans up the messes left by his master, Don Juan. Over the course of the play, Don Juan manages to enrage one Doña Ana and her father, a vengeful Tisbea, and even a young bride-to-be, Aminta, and her groom, Batricio. To top it off, Doña Ana’s father gets unjustly killed by Don Juan, and comes back in time to haunt the Don over dinner and drag him off to hell. Sound familiar? You can give it a read for yourself.

The story of course ruffled some puritan feathers, but such is the tale of all the best art. Molière played the role of Sganarelle, the servant, in his play, Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre in 1660. Tisbea becomes Elvire, and the central action of the plot surrounds Don Juan’s lies to the poor woman, and her brothers who attempt to avenge her honour. Don Juan still kills a Commandant, who comes back for ghostly dinner and serves up justice.

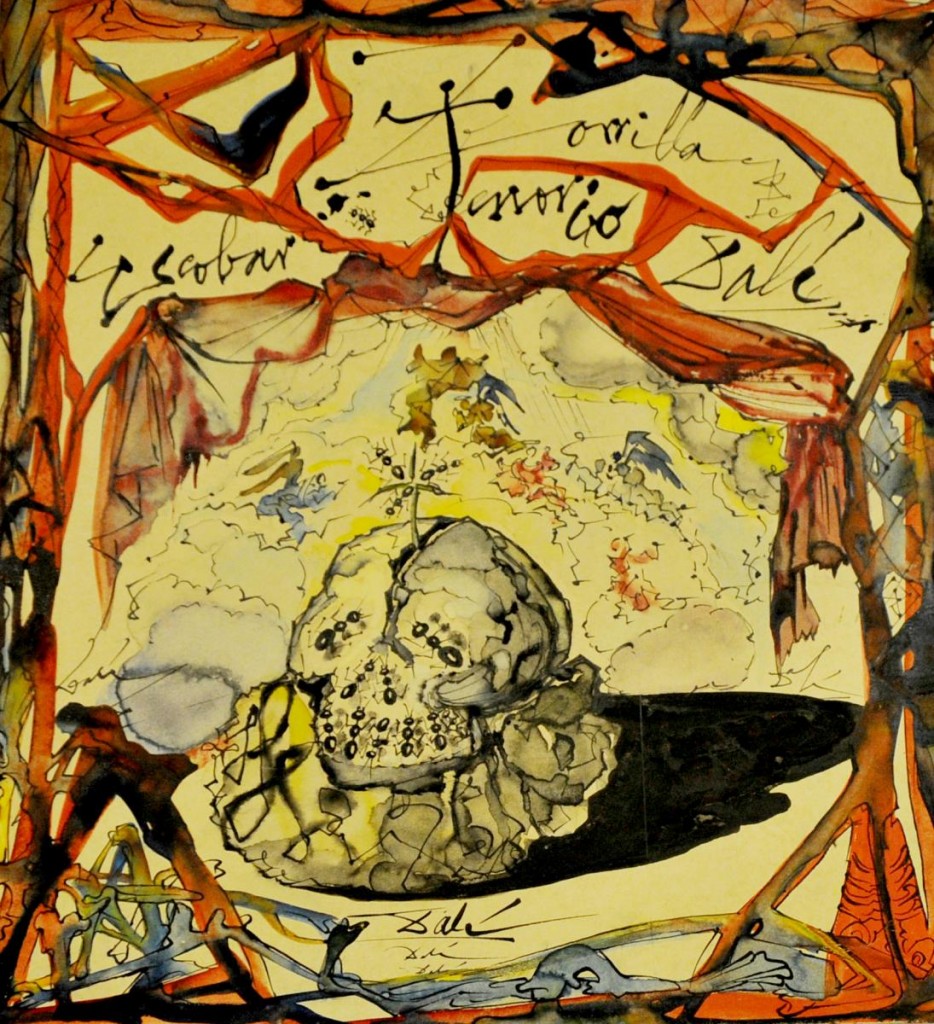

Italian composer Giuseppe Gazzaniga beat Mozart and da Ponte by a few months in the opera department, with his _Don Giovanni Tenorio o sia Il convitato di pietra _(Don Giovanni Tenorio, or The Stone Guest), which premiered in February of 1787. The work was shorter than Mozart’s, appearing as part of a double bill, but Lorenzo da Ponte certainly knew of Gazzaniga’s Giovanni. (Gazzaniga’s Don Giovanni always makes me think of poor Leoncavallo’s La bohème.)

After Mozart and da Ponte’s Don Giovanni opened in 1787, the piece fuelled more and more faces of Don Juan. E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote his 1813 novella, _Don Juan: A fantastical event that befell a music enthusiast on his travels, _in which the protagonist attends a performance of the opera, and is enamoured with the spectacle, as well as with the sight of the singer playing Donna Anna. Lord Byron, between 1819 and 1824, wrote 16 poems (and one unfinished) on the story of Don Juan, calling it “Epic satire”. The critics ranted about immoral content, but the readers devoured the poems. Don Juan even made it into Russian literature, in the form of Alexander Pushkin’s 1830 play The Stone Guest.

Even the moral questions raised by the story of Don Juan are timeless. Some of my absolute Don Juan philosophizing is by Søren Kierkegaard, in his Either/Or. Using the pseudonyms “A” and “B” (or The Judge), Kierkegaard presents two polar ways of life, the pursuit of pleasure and the pursuit of ethics. The question is simple enough: how should we live? Kierkegaard finds a perfect example of the aesthete in the character of Don Juan, who is insatiable in his desire for more women. This insatiate cannot enjoy the woman he has now, because he already desires the next. In line with the oldest prescription in the book, the answer to the question, “How should we live?” is a combination of seeking pleasure and consideration for others. Moderation, and all that.

Mozart and da Ponte’s _Don Giovanni_ has seen plenty of evolution since its premiere in Prague on October 29, 1787, perhaps hitting an unnecessarily tacky wall with Kasper Holten’s filmed version, Juan. (I mean, either make a movie about Don Juan with Johnny Depp in it or leave the opera on the stage, am I right? Some purist veins, have I.) But one large digression from its “original state” is the size of voice. Opera singers who are considered fit for today’s performances of _Giovanni_ would have sounded Wagnerian by comparison. We know the cast included some singers who were pretty darn young, by today’s standards. Luigi Bassi, who sang the first Don Giovanni, was only 24 at the opera’s premiere. The Donna Anna was 24-year-old Teresa Saporiti, who had a pretty short vocal career, but apparently was at least a knockout to look at.

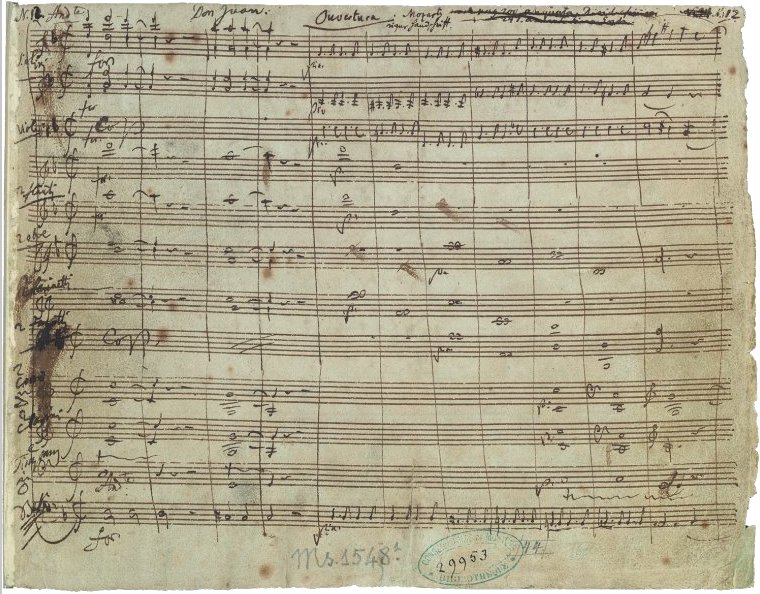

And they improvised. Don Giovanni was supposed to premiere on October 14th, 1787, but the singers added to several delays, according to letters from Mozart: “Everything dawdles along here because the singers, who are lazy, refuse to rehearse on opera days and the manager, who is anxious and timid, will not force them.” The so-called opera days were one out of every three, which left a horrifyingly short rehearsal period for a piece like Giovanni. It’s an educated assumption (and the late Charles Mackerras agrees with me) that the opera was not learned with the level of detail that we consider acceptable today. Luigi Bassi, after a later performance of Don Giovanni in Dresden, spoke about keeping the show fresh for its audience: ”[The supper scene] lacked the liveliness, the freedom, that the great master wanted in this scene. [In Prague] we didn’t sing this scene the same way two evenings running. Without keeping strict time, we cracked jokes—new ones every night—and just kept a careful eye on the orchestra. Everything was virtually spoken, as if we were improvising, as that is what Mozart wanted.“ Consider that Mozart arrived in Prague on October 4th, to begin rehearsals for Don Giovanni, with huge chunks of the opera still left to write. He hadn’t touched the overture, Zerlina and Masetto’s entrance, the entire graveyard scene or the finale. It is said that Mozart was still scribbling out orchestral parts to the overture the night of the premiere, delaying downbeat by almost an hour. Ballsy. Also, less control-freaky.

So, we’ve got decidedly young voices onstage, and both the music and libretto were not set in stone (pardon the vague pun). To top it off, the theatre that housed the premiere was teeny tiny. The Estates Theatre in Prague held around 800 seats, making most desirable opera houses of today look obese. Not only was it small, but ill-lit, and it had acoustics that were bad enough to warrant selling copies of da Ponte’s libretto for the audience members who cared enough to follow along. Compare this evening at the opera to, say, Ferruccio Furlanetto and Carol Vaness hollering out Mozart at the Met in 1990, and it’s a real apples-to-oranges situation.

And so, we finally come to the newest permutation of the Don Juan tale, in the form of Against the Grain Theatre‘s #UncleJohn, set to have its first performance at the Cave and Basin National Historic Site in Banff, Alberta. There’s nothing conventional about it. Da Ponte’s Italian has been morphed into director and librettist Joel Ivany’s English adaptation, and Mozart’s music inevitably takes on a new dramatic intent. Purists will stay ruffled if they so desire, but what’s timeless about the Don Juan story will never be absent, no matter how it’s packaged. I’m thrilled to join a team of creative folks who will join the line of imaginations that keep posing these eternally relevant questions. How _should _we live, indeed?

Stay posted at Schmopera to get some answers from Against the Grain Theatre, The Banff Centre, the Canadian Opera Company, and of course, the #UncleJohn cast.

Comments