Aria guides: Una voce poco fa

How-ToFor the next in our series of Aria Guides, we’re nodding to all the mezzos (and a few sopranos) with “Una voce poco fa,” from Il barbiere di Siviglia. This is a cornerstone aria for many young mezzos, and one of the few chances they have to show off coloratura and play a girl. It’s also an aria full of options. Ornamentation, cadenzas, high or low keys; there’s no “right way” to sing rep like this. I can offer up a few tips based on common traps and hurdles I’ve noticed as a coach.

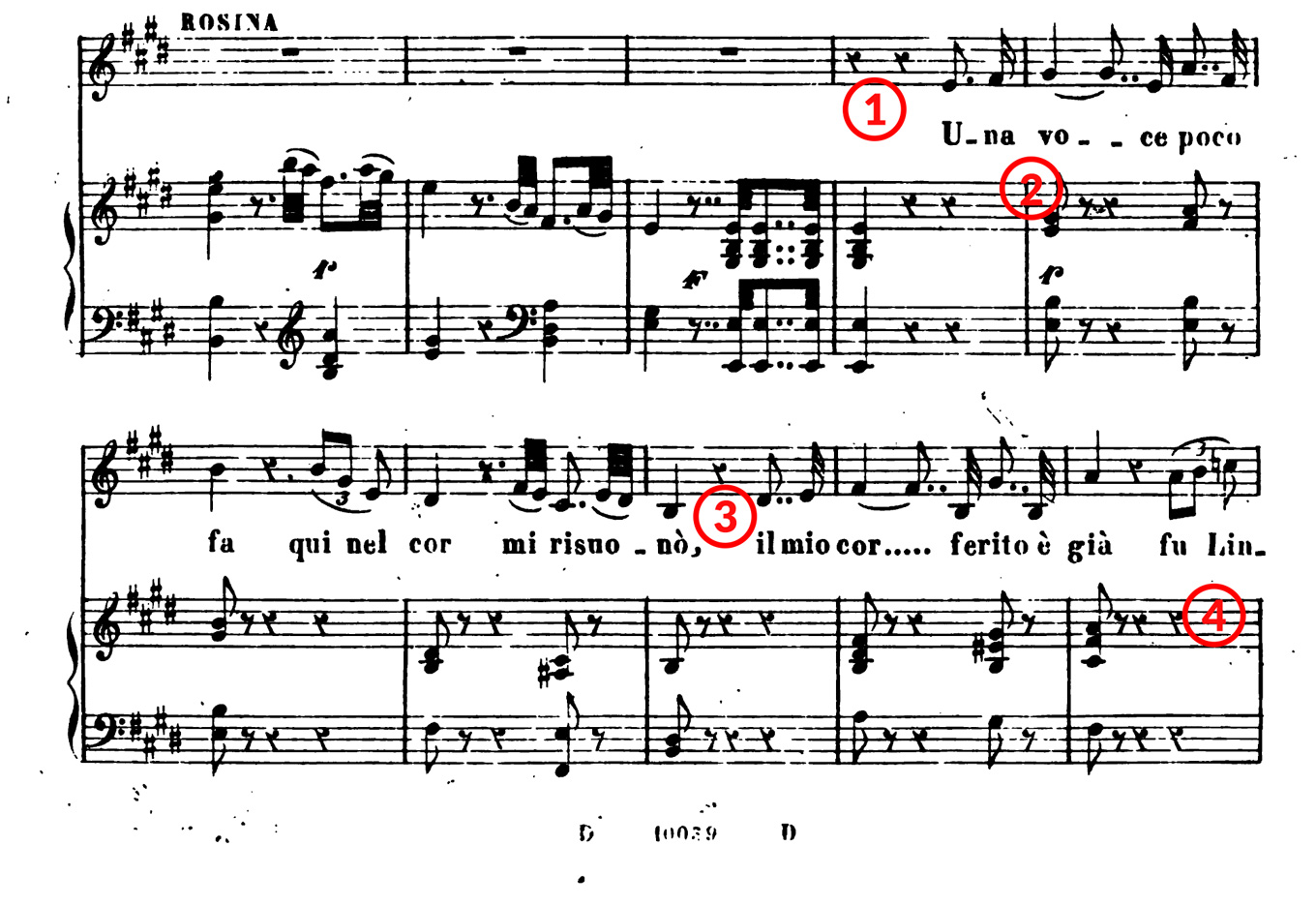

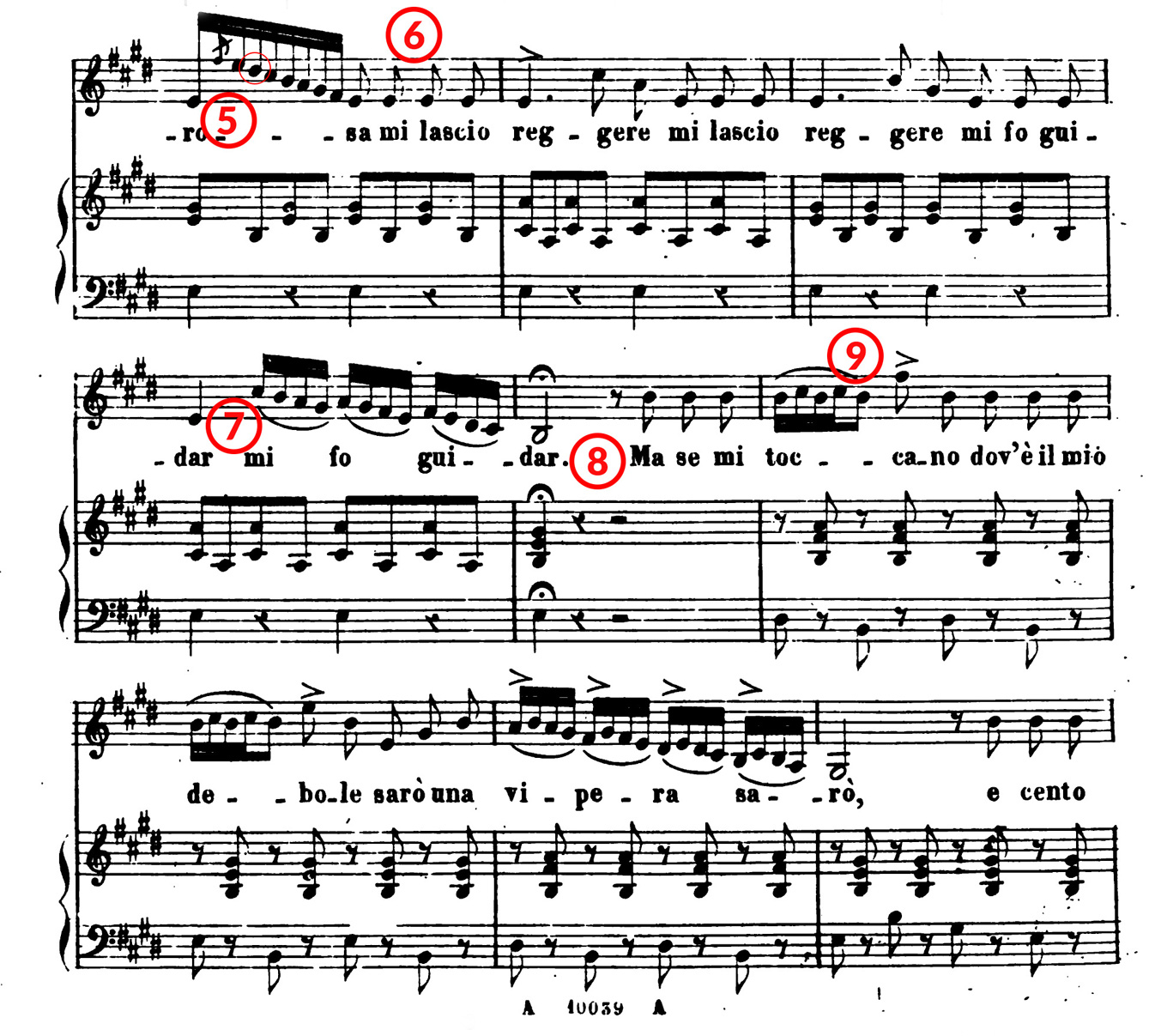

Follow along on page 82 of this score, or use the excerpts below. For suggestions, or to request an aria, get in touch at [email protected].

The slow part

- Rhythm matters. Be precise, and be brave with these double dotted figures. Practice subdividing into thirty-second notes to feel how long the “u-” of “una” really is. The trick is in making continuous sound through the double dotted figure, without anticipating the short note. Although they’re more precise than grace notes, the thirty-second notes will feel attached to the long notes in a similar way; it’s a “ta-DA” figure. Bonus tip: be very careful not to double the N in “una”; this often gets related to rhythmic precision, so be sure you’re not counting with consonants.

- Singing through the V in “voce” brings the text to life. It’s not quite a double V, but it’s giving the word some attention.

- There’s a tendency for the E natural on “il mio cor” to be sharp; take care with intonation as you get this aria into your body.

- That C-natural on the name “Lindoro” should really mean something. Sing the “Li-” fairly long, as though it has a tenuto marking; if the [i] vowel is in a good spot, you’ll also be able to sing on the N in his name.

- This is a strangely written lick downward, and it’s easy to get tied up with rhythm and notes. Take note of the repeated note pattern (circled); you don’t actually have to think about singing a pitch twice in a row. You can get the right effect by placing the text with the grace notes (before the beat), and singing through any repeated notes like they’re one long pitch instead of two. It’ll be easier, and it will sound more legato than yodel-like.

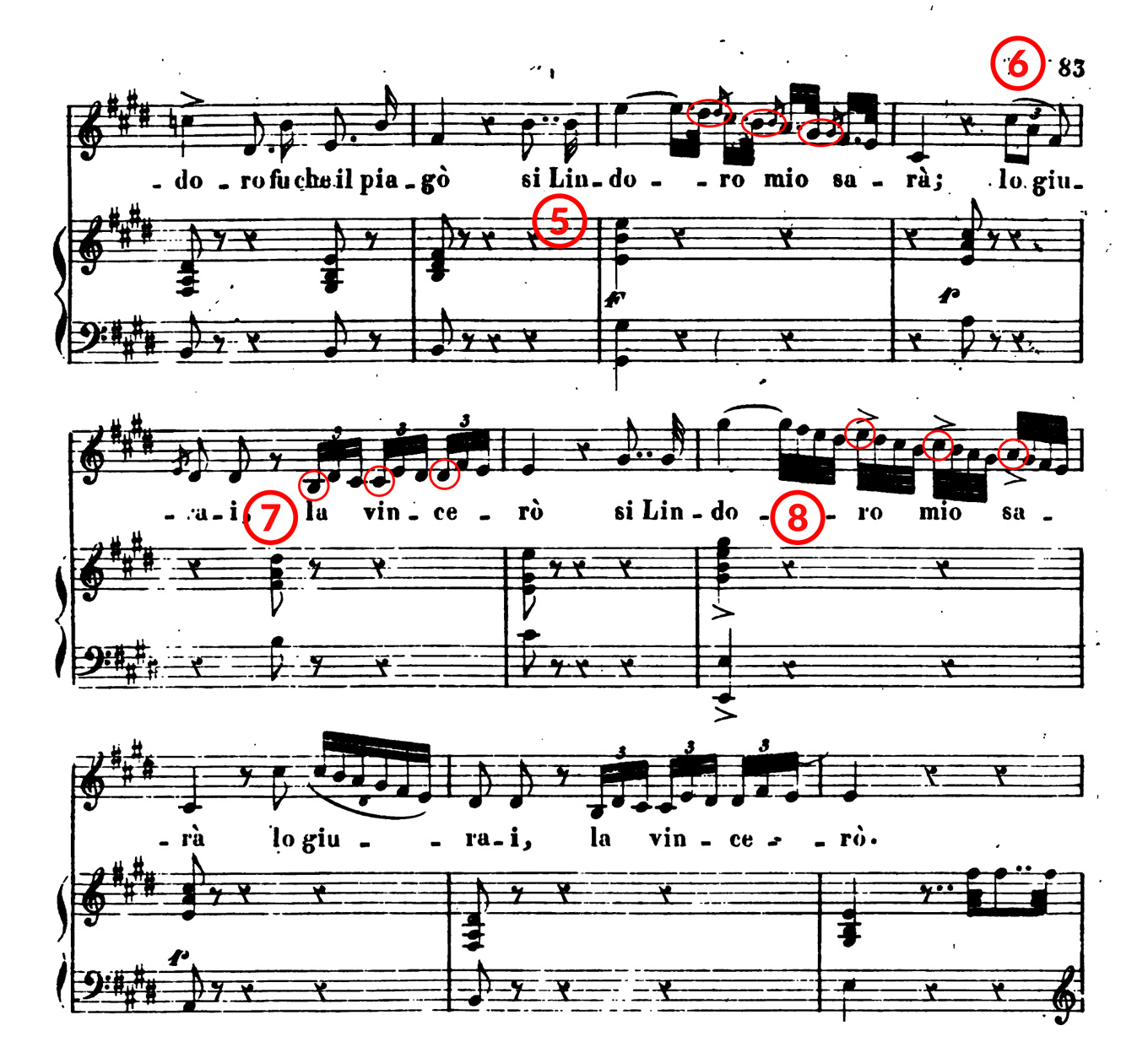

- I’ve noticed a habit of singing in straight tone for this descending triplet under “lo giurai”. At the very least, give some attention (read: vibrato) on the “giu-” to keep the bel in bel canto.

- The little rising passage on “la vincerò” has repeated notes in it, similar to the grace notes earlier. Let each pair meld into one note, divided only by a change in text. The frame of this melisma is really in the first of each triplet, a rising B-C#-D# pattern (circled). Keep hearing this hidden melody so you stay grounded instead of frantic.

- There’s another one of these hidden melodies in the big melisma down from the G# on “Si, Lindoro mio sarà”; the starts of each group of four thirty-second notes outlines the descending G#-E-C#-A frame in eighth notes. As you practice this melisma, use this larger tune to stay organized technically and harmonically. Sounds boring, but it makes your job a lot easier.

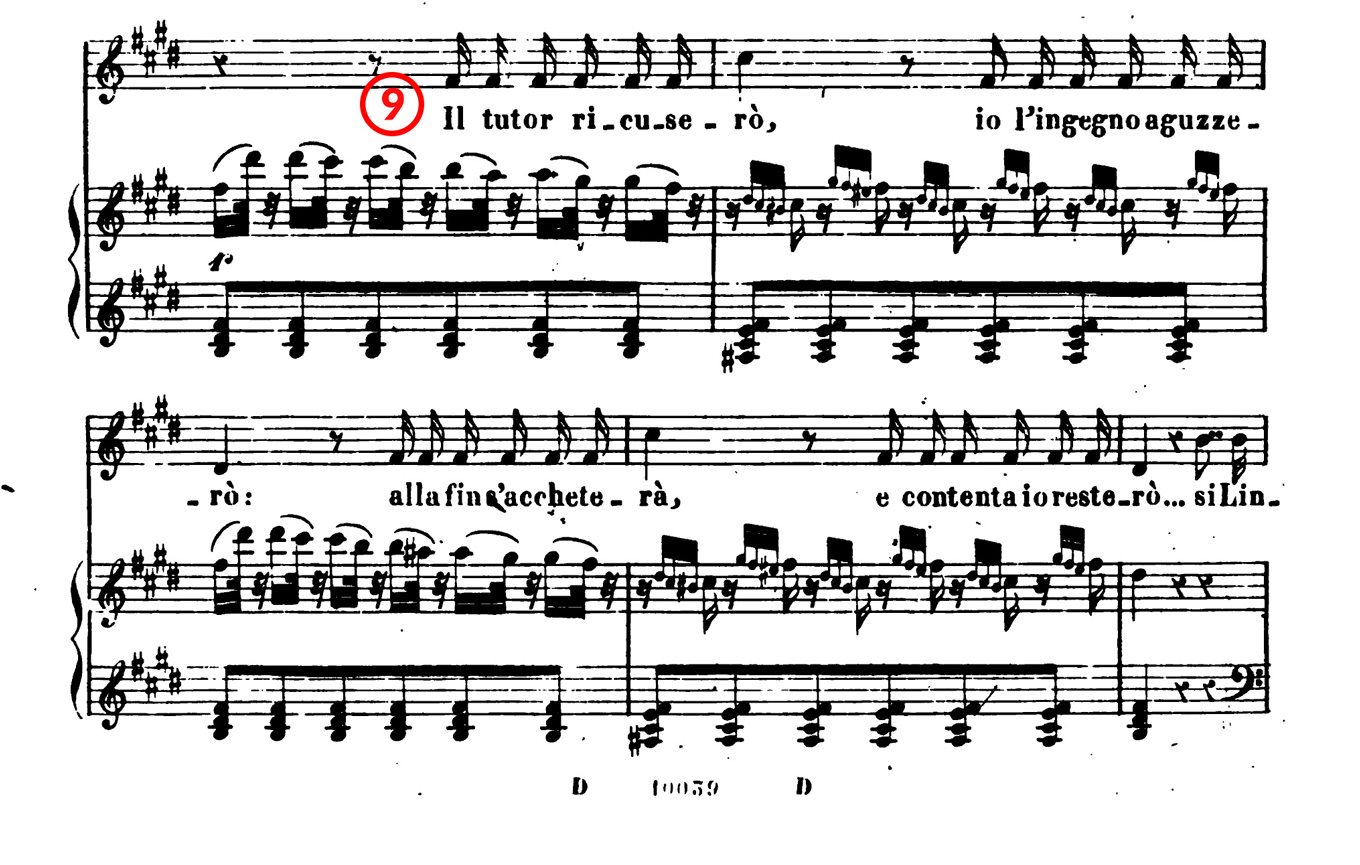

- This section is about text, not singing; for that reason, you should feel free to take Rossini’s rhythm with a grain of salt. The ebb and flow of the Italian should take precedence over even sixteenths, and it’s a dead giveaway that you’re not comfy in the language if it’s robotically even.

*As this section repeats and you add your ornaments, your to-do list should be fairly short: choose ornaments that show off what you do well (in reality, not wishful thinking), and don’t overthink your choices. Opinions are abundant, and if you’re hired by someone with strong enough thoughts on how to jazz up this aria, they’ll tell you what they want to hear anyway. Go nuts, have fun, but don’t give yourself a chore to do each time you sing it.

The fast part

*As we get into the coloratura bits, I can offer some general, if incomplete, advice. Help yourself by always finding the larger tune within the string of sixteenth notes, and stay nice and light. For more specifics, get thee to thy voice teacher.

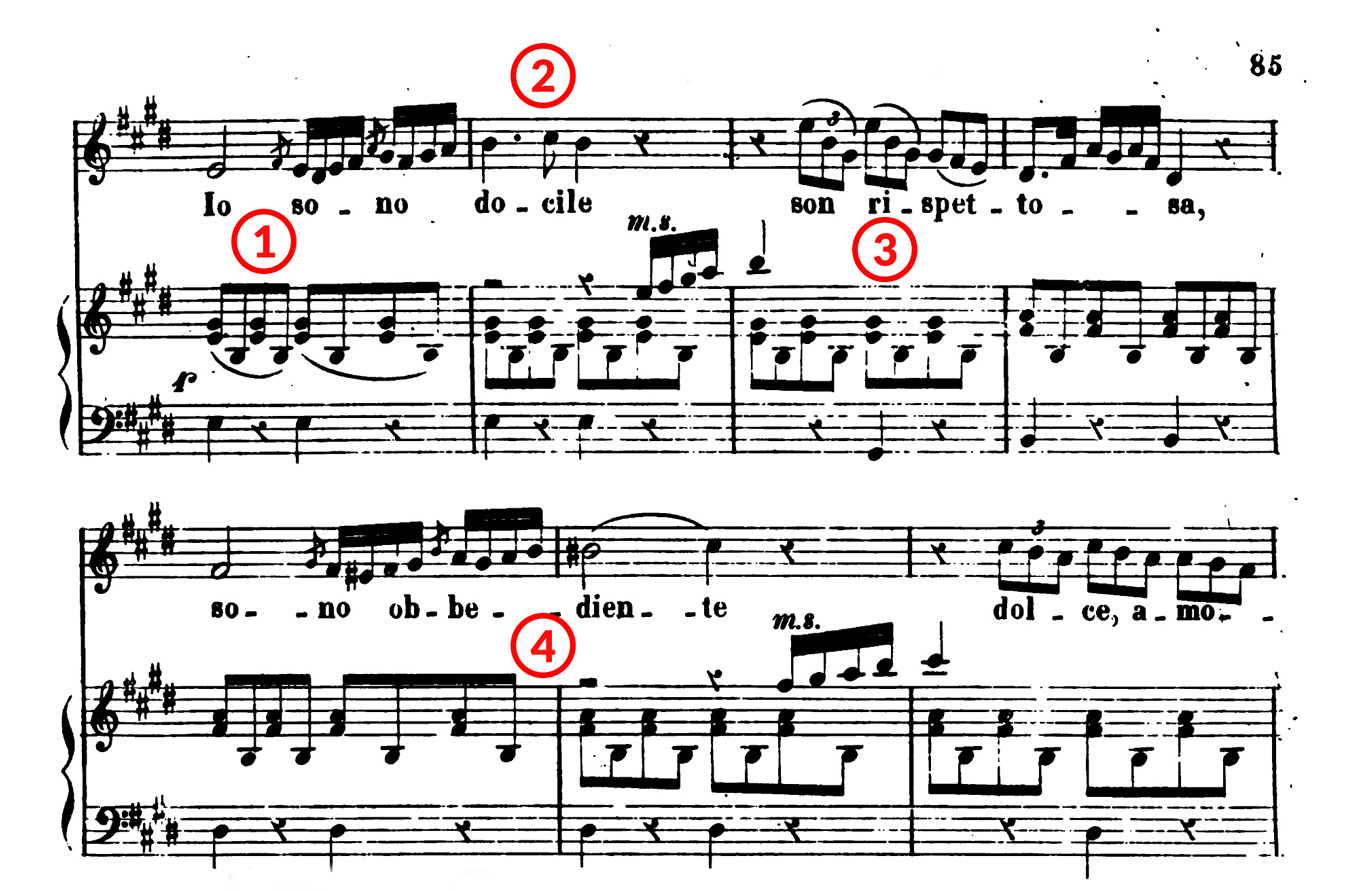

- Give yourself lots of room to sing the 5-note figure (4 sixteenths and a grace note) on “sono”, by starting the “S” nice and early.

- Be sure that you’re singing (read: vibrating) on the “ci-” of “docile.” It’s a tiny detail, but that little C-sharp can have a lot of character. Like a wink, but musical.

- Double check your intonation on the low G# of the triplet passage under “rispettosa” (it’s a tuning trap!).

- Be sure you can sing the N in the word “ubbediente” (in some scores it’s “obbediente”). If the [ɛ] vowel isn’t in a great spot, that N won’t come out; it’s a nice test of your technique, and you’ll sing right in the centre of that beautiful B-sharp.

- This scale is tricky, considering the octave leap involved and not much room for rhythmic flexibility. If you double check the D# (circled), just as you begin the descent, you’ll find you’ll be more accurate, and less likely to “fall” down the scale.

- In these low E’s on “mi lascio reggere,” imagine you’re singing 2 beats to the bar rather than 4. There’s a tendency to make these eighth notes heavy and to chew the text; a feeling of 2 will help lead you to downbeats, rather than sit heavily on each syllable.

- Like earlier in the aria, there’s another large-frame melody hidden in this melisma on “mi fo guidar.” Let the descending third pattern (C#-A-F#, circled) ground you and organize this bit of technique into something musical.

- It’s pretty fun to do a portamento up from the low B natural, and make a whole thing out of the rolled R in “guidar”. I feel like this is one of those things that non-Italian speakers do, and I wouldn’t assume that it’s as funny for native speakers as it is for us. Whatever effect you want to do on “guidar”, make sure you could also deliver the same subtext without relying on the R sound.

- The accented notes on “trappole” and “cedere” should be singing accents, not pressing accents. They should allow you to let your voice ring (read: vibrate) for a moment, like a release of any tension that might come out of the small place your coloratura lives.

- This scalar passage doesn’t have a hidden tune in the way that previous melismas do, but there’s still the opportunity to anchor yourself in the midst of all the notes. Use the notes on the big beats (circled) as checkpoints to keep you on track.

- This section is full of personality, with all its sliding chromaticisms. Be very picky about intonation here, especially when it comes to showing a minor versus a major mode.

- When you ornament that same figure in the dotted rhythms, pay attention to how you sing the long note. In this rhythm it’s easy to lean on the short note, decay on the long, and then forget about it. Without getting heavy, make sure that the long note is flexible and truly in your voice (rather than simply intoning a pitch).

- As you do this pattern of descending scales, it’s easy to get tired and fall down from the top note, like in the “amorosa” bit earlier. I’ve found that pinpointing the intonation of the second note of the scale helps a lot. So, the F# in the first scale, the E-natural in the second, etc. (Circled for clarity.)

- This next bit is where you can coast. It’s all about the orchestra’s Rossini crescendo, and Rosina’s interjections aren’t worth trying to cut over all that noise. Take the opportunity to deliver these short lines in a parlando way, resting up for the grande finale to come.

- More coasting here. The orchestra is getting excitable (read: louder), and Rosina’s line is more functional harmony than bel canto. It’s an easy line to sing and you’ll probably be full of adrenaline by this point; all you really need to think about is staying light and staying high in your placement. There’s a high B coming up (or C, if you’re high-keying it)!

- It’s common performance practice to tacet for one or both of these bars of quarter notes. Most singers come back in at the start of the measure with the high B, on “ah”; the orchestra usually cuts out after the last chord of that bar, and waits for Rosina to sing the big high note. It’s up to you whether you want to sing the last “farò giocar” as written, or with ornaments, or simply pop the high note out of the blue. Whatever you choose, make sure it’s something you could do under pressure.

Comments