Aria guides: Cortigiani, vil razza dannata

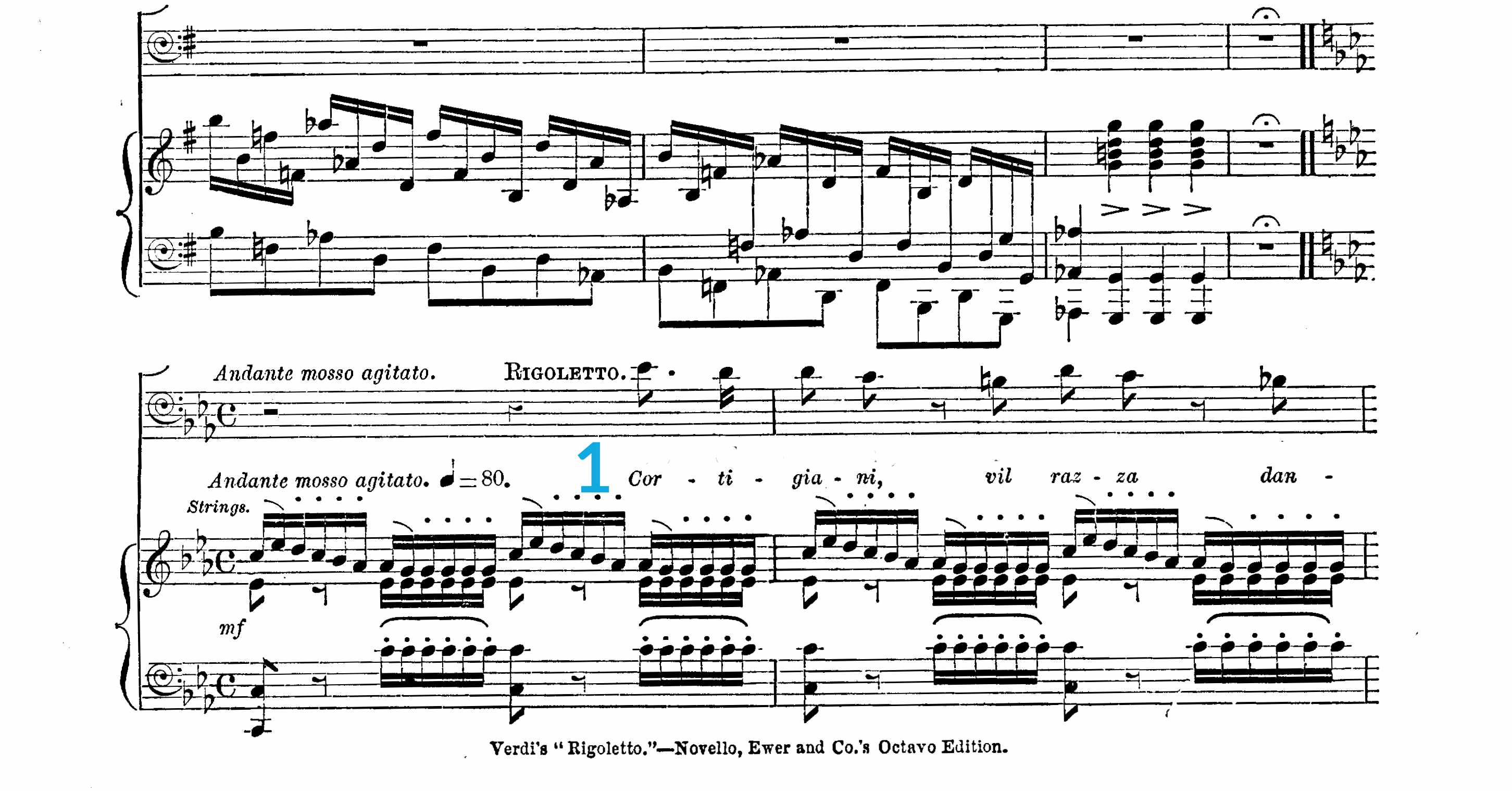

How-ToThe music here (1) is so darn great, it’s one of opera’s great adrenaline rushes. Throughout this whole section, keep a swinging feeling of 2⁄2; it’ll be much more freeing than the 4⁄4 that’s actually marked, and it’ll keep you from falling into the trap of dragging the tempo. Some baritones holler this section, citing Rigoletto’s seething rage in this scene. I implore you, baritones, to sing it beautifully, and let the text and music do the dramatic work for you. This section is so powerful when you sing each note, including in the vicious dotted rhythms. Even more important are the non-dotted rhythms, like in “vil razza” - that’s an important detail that relays rage more effectively than any baritonal woofing could.

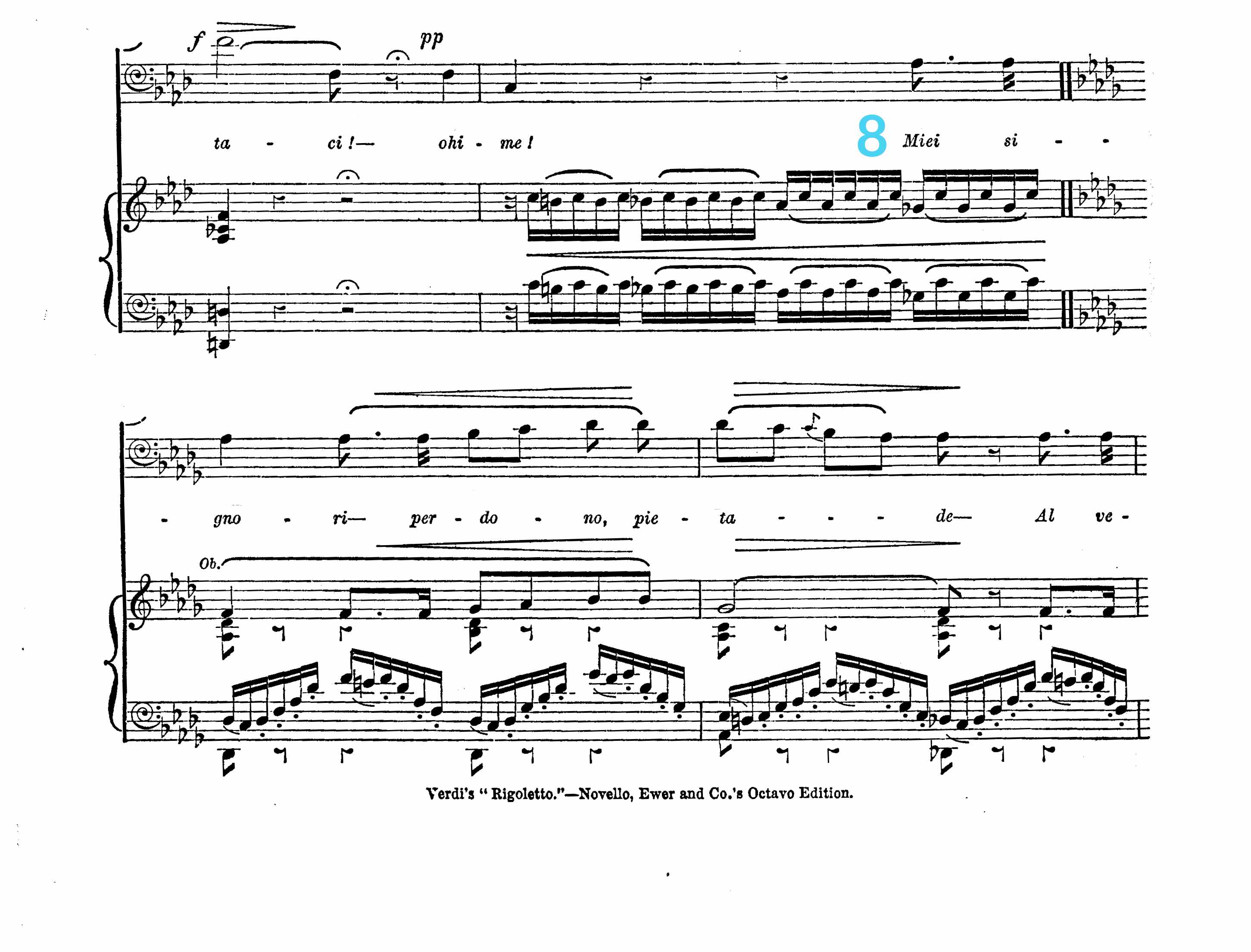

In the practice room, try out lines like these (2) without the dotted rhythms, as though each note value is the same. It’ll make sure you know where the D-natural sits on “mia”, and that C-sharp in the middle of “impagabil”. This kind of detailed work is what creates that super important bel canto legato, and ensures that you’re singing every note with an actual vowel.

Despite the rests, this (3) is still one long phrase; let the text lead you, not the silences, and beware the bad habit of taking a breath each time there’s a rest. Wherever you have longer notes - “pur”, “questa”, “fora” - remind yourself of what vowel you’re singing; it’s easy to let vowels get vague, so think of renewing, or repeating the vowel as you keep it spinning. On “Questa man”, really sing that D-flat, because it’s a great note.

This (4) is a section to coast, not spend. This should feel speech-like, not like you’re hyperventilating. Think of these three bars as a big lead-up to “Ah!”

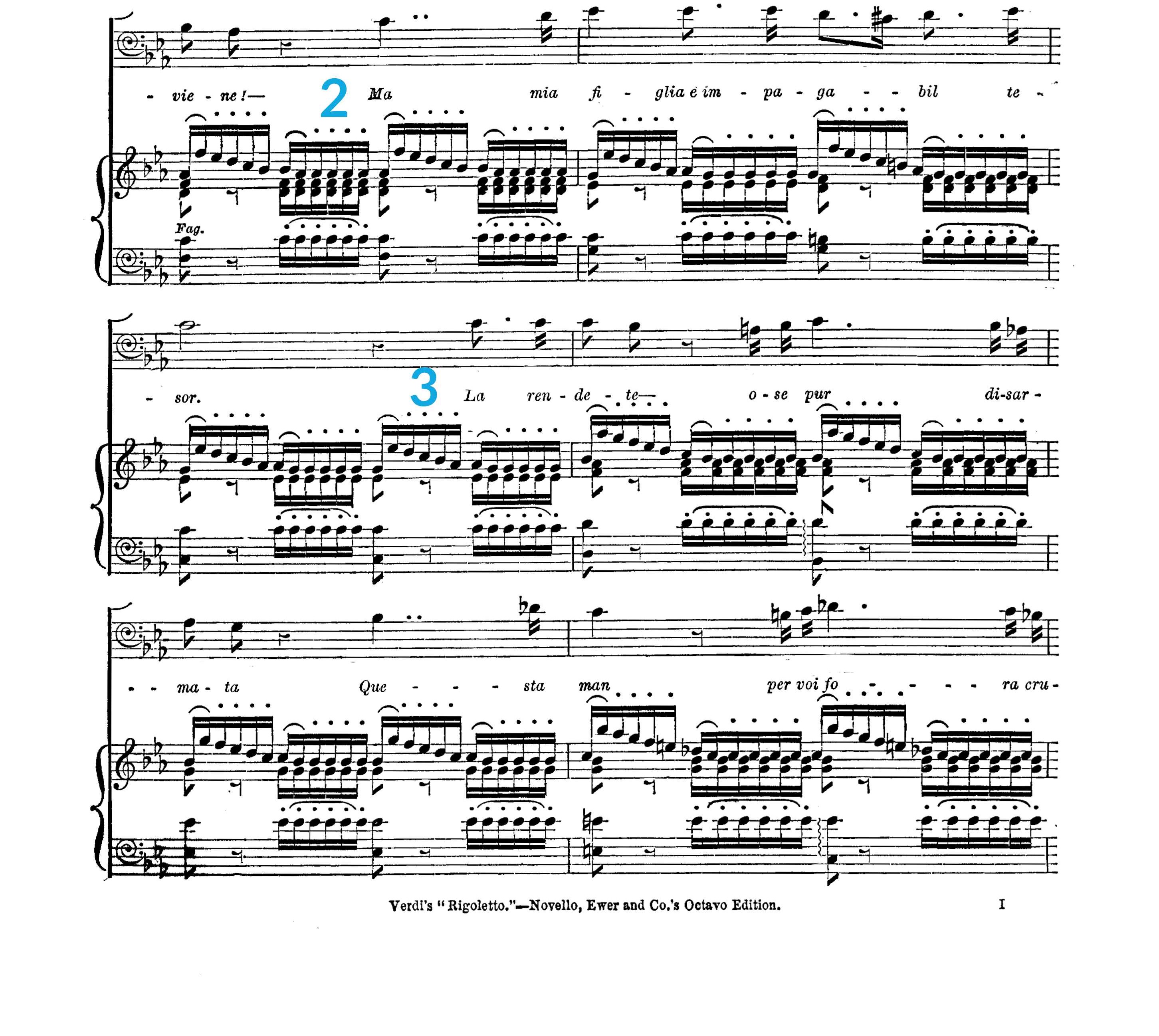

Verdi slows the tempo here (5), just in time for a dramatic shift into the world of weeping. When Rigoletto says, “Marullo, Signore”, it should feel utterly pitiable. The effect is amplified by being really picky about the rhythm; note that you’re singing straight eighth notes, against the orchestra’s triplets. At “Tu ch’hai l’alma…” let the crescendo help you spin that whole phrase.

This phrase (6) can surprise you, so at “Dimmi tu” make sure you’re breathing for the higher tessitura in the next bar.

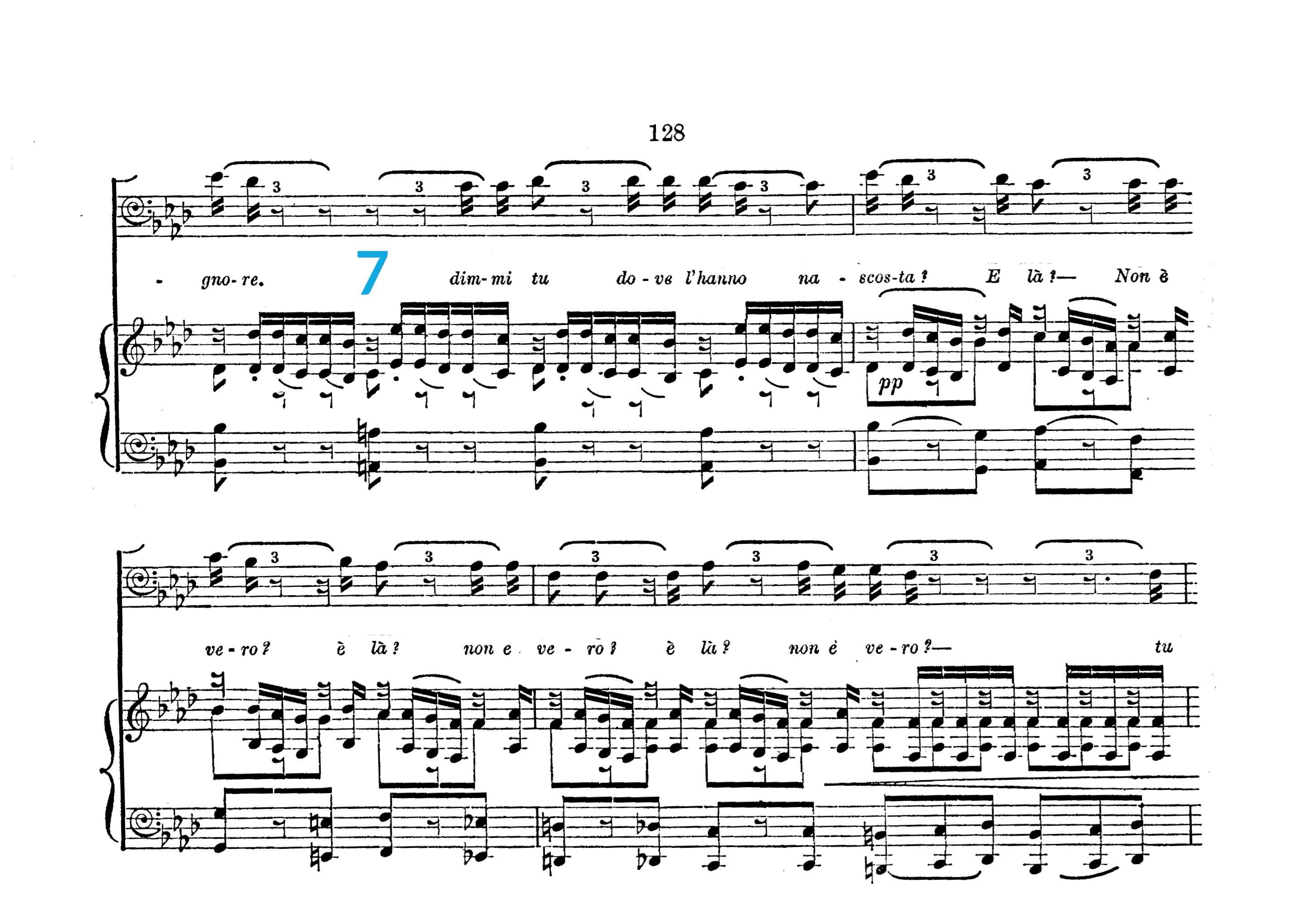

It’s another speech-like section here (7), one that shouldn’t wear you out. Beware of sipping breaths in each rest, and keep some lightness in your sound as you descend, so you don’t relax too soon. Hint: there’s a high F coming up! (And in case you’re wondering: I didn’t put in an entry for “tu taci” because it’s best left between you and your trusted teacher.)

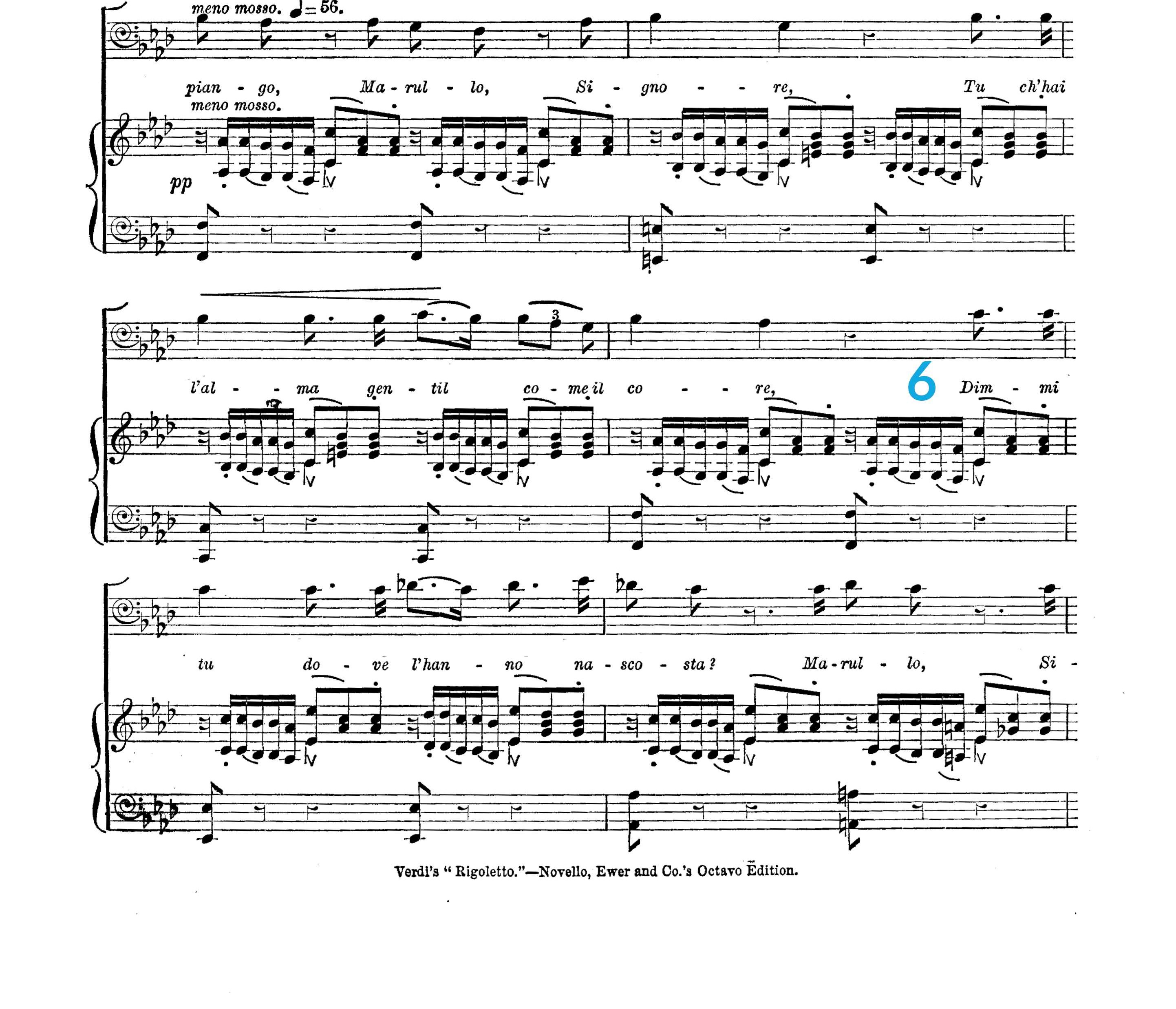

Another great moment in opera, right here (8). Please, for the love of Verdi, make sure you’re vibrating on this pickup - including the “si-” of “signori”. We’re into full-throttle bel canto here, and you’ve got lots of help with the crescendo and diminuendo up and down from the D-flat. Verdi gives you lots of these tools, so take them literally, for your own sake.

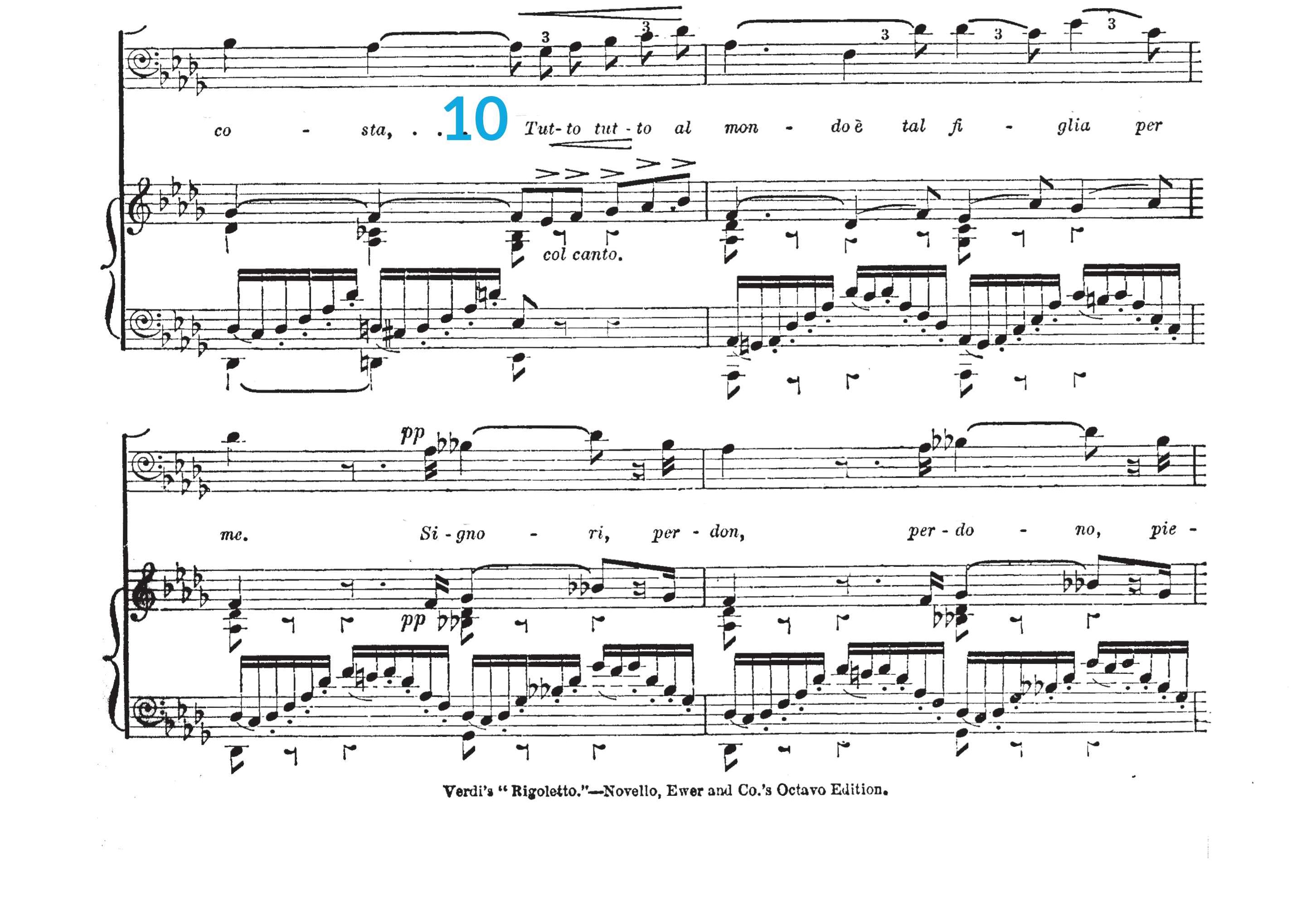

Verdi gives you a proper portamento here (9), so enjoy carrying the [i] vowel up to that D-flat. Don’t skip the sixteenth note on “voi”; if you’ve taken a wise breath before “Ridonarla”, that “voi” should help you up to the E-flat. And with those pesky slurred staccatos on “a voi nulla ora”, consider them deliberate, rather than detached. The orchestra can do detached - you do bel canto.

Verdi marks col canto here (10), which means you’re the boss! Don’t get greedy, but you can definitely show off - provided you snap back into tempo at “mondo”. The pianissimo in the second line is another dramatic shift, and it’s all relative; go for dynamic contrast with the previous phrase, not a specific volume level. In the portamentos on “signori” and “perdono”, think of getting to the D-flat early, to keep these mini-phrases flowing forward.

This section (11) is totally tricky. Consult your teacher immediately. But in case it helps, I can suggest that you treat these two lines like a marathon, and not a sprint; as you descend down from the first high F, keep height in your placement so that you’re not surprised by round two. And usually, you get to take some time when you reach up to the high G-flat.

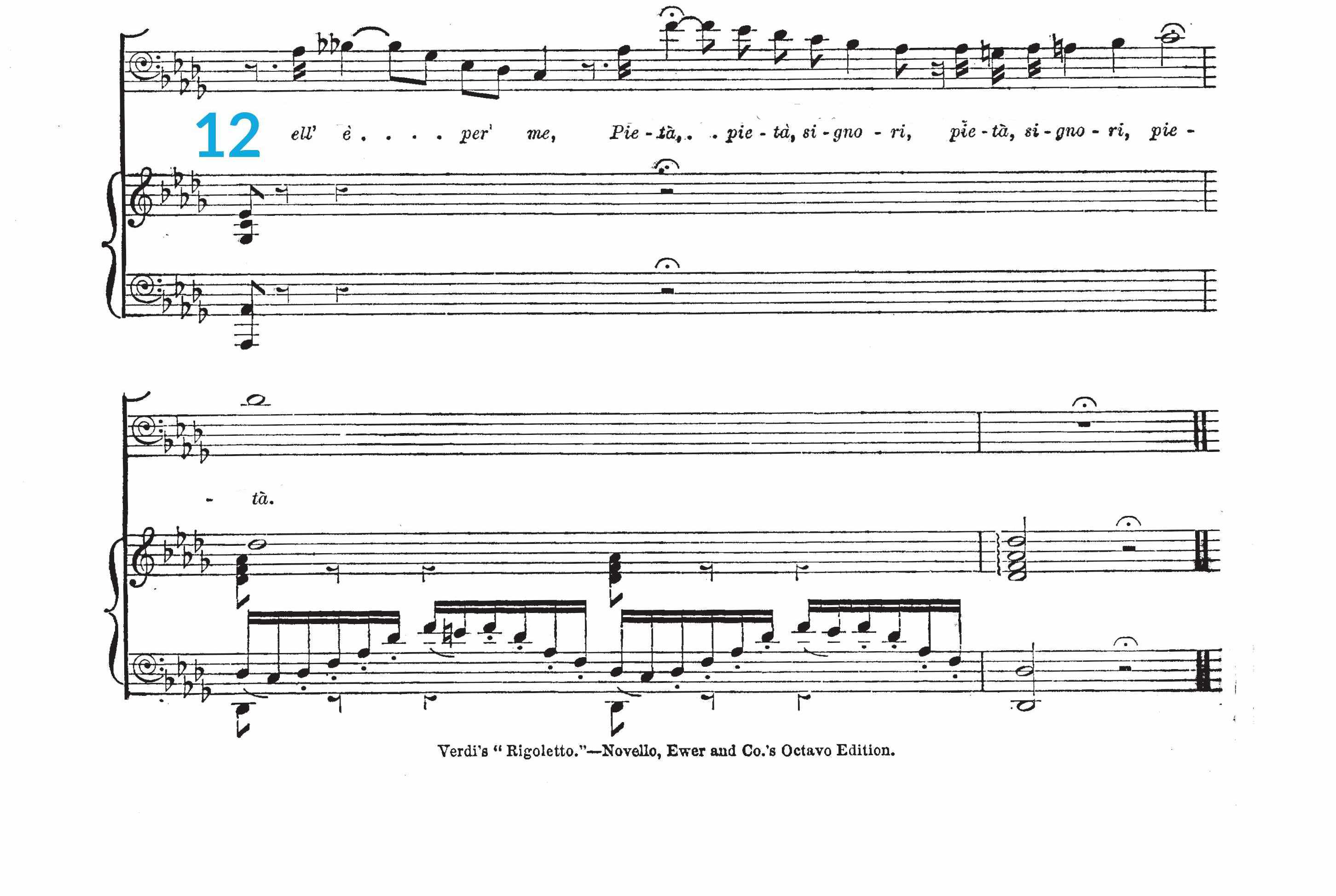

Who doesn’t love a cadenza (12)? First step: don’t overspend on the low C. And though it’s true you don’t have to beat time during a cadenza, there’s information in the note values. Eighth notes are longer than sixteenths, so keep that in mind when you come down from the high F. In the last “pietà”, enjoy singing (and vibrating!) through the [j] glide in the first syllable. And finally, you get a bonus point for every extra beat you hold that last note. It’s an unofficial Verdi rule.

Baritones, we made it! High five. Now to listen to a pro: I’m partial to Leonard Warren’s version, personally.

Comments