Aria guides: "Come Paride vezzoso"

How-To- Right off the bat, Donizetti writes a pillar of bel canto style, and that’s the dotted rhythm, versus the triplet. It may sound like a subtle different, but singing this first phrase with a triplet feel completely changes the character of the music. There’s something pompous and overdone about sticking to the tight dotted rhythms, which is exactly what Belcore is all about. Think of the dots as double or triple dots, and pull as much vowel time out of the long note as you can.

- These triplets on “porse il pomo alla più bella” are in a tricky spot of the voice, but that’s not what you want to advertise. On “porse”, leave room to vibrate comfortably on both pitches; on “alla più bella”, make honey out of the word “più”.

- This phrase should be funny, but not unbeautiful. It’s should sound like Belcore thinks that Adina has never even seen a flower before, let alone be given one. While you’re up there on “porgo”, let the great rolled R add to the flourish; on the fermata over “questi”, give it a dramatic impetus. Either he’s drawing out the suspense (read: laying it on thick), or he’s temporarily forgotten where he stashed the flower.

- Belcore is getting a bit more serious here, and you can hear it in this temporary minor key. Get really picky with your intonation on the B-flats and E-flats. You can also try and stretch a bit of time out of the word “più” to play up the overcompensation that’s going on.

- As you get out of this cadenza, there should be a sense of tempo. There’s nothing wrong with milking the top E, but by “premio del mio”, a conductor or pianist should feel you sliding back into tempo.

- There are some fun word painting opportunities here, and the more you overdo it, the better it will be. There should be oodles of confidence in “Veggo chiaro”, and you have the time to stretch the high D to make it sound a bit more “chiaro”. On “ch’io fo breccia nel tuo petto”, you can play up the “breccia” bit, and you can afford to be a bit heavy-handed. Belcore is showing off what he thinks are mad skills, but the joke is he’s telling everyone that he’s a brutal date with cheesy moves.

- More corny word painting here; the melisma on “sorprendente” should be a bit of a bluster, like some overly slick move on the dance floor that ends up knocking over a few people instead. When you get to “galante”, stretch the “ga-” syllable so it’s nice and overcooked.

- For this bit of coloratura, stay light, especially over the tied notes. It’s easy to lag behind if you sit on the longer notes, so think of coming away from them, almost releasing on the tied note. The effect is almost as if the three sixteenth notes lead forward to the next beat, rather than a ricochet away from the preceding long note.

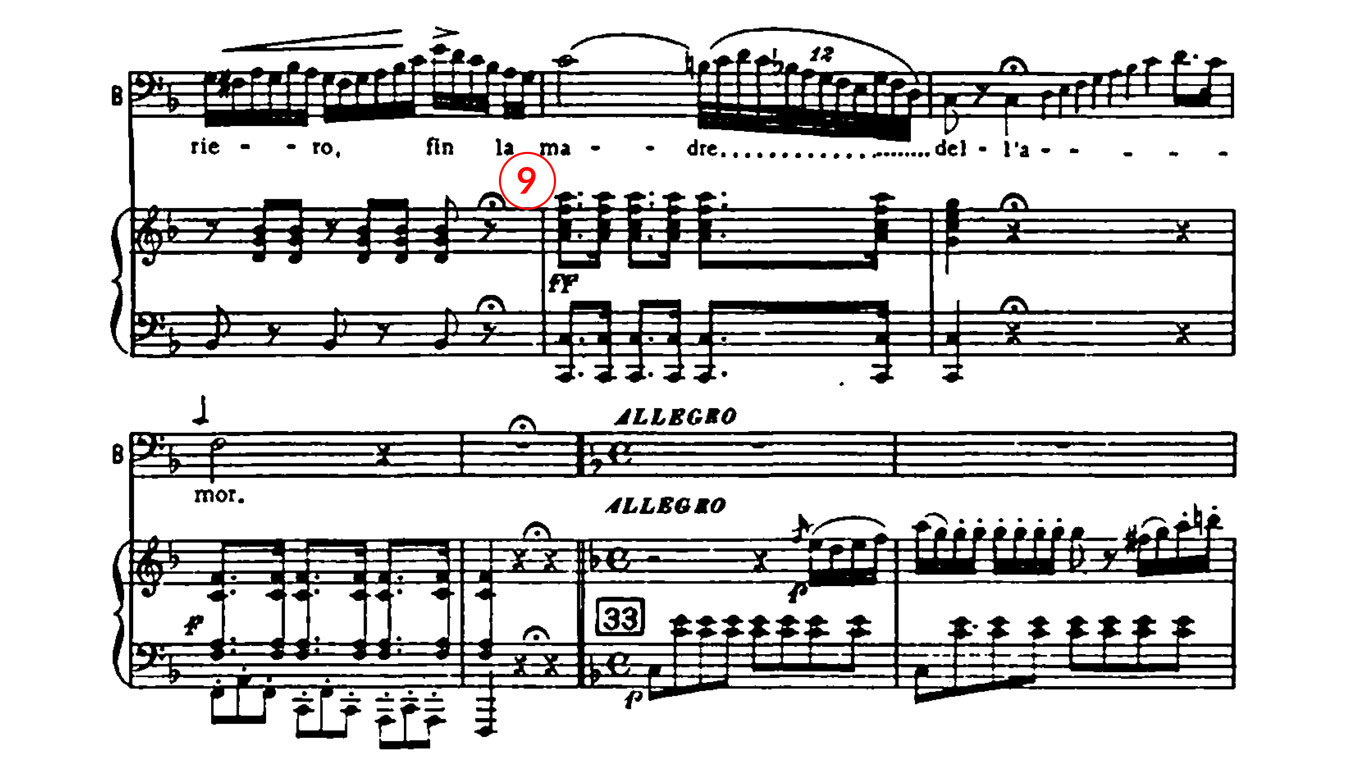

- It’s common to alter this bar a little bit, so that you hold the long C until the orchestra plays that last chord of the line. Some may disagree, but it at least lets the audience hear your melisma more clearly, and it allows for you to shift the text around so it’s a little less strange. Some baritones sing the word “madre” all on the long C, take a breath, and then since the melisma on a separate “ah”; they do the last scale upwards on “dell’” and wait until the last C-F to place “amor”. Our personal taste: move the “madre” melisma to after the orchestra cuts out, but do it on the “ma-”, and land on the “-dre” at the bottom; then, the scale up is on “dell’”, and “amor” take the last two notes of the aria, with a nice portamento between them for a finishing touch.

Have an aria you’d like to see in our Aria Guides? Let us know at [email protected].

Comments