André Tchaikowsky's only opera: The Merchant of Venice

ReviewThe opera begins and ends on Freud’s chaise lounge. Antonio, a young Venetian businessman is tossed on a sea of melancholy. He yearns to know why he so sad. Three acts later, he is back on the chaise in the opera’s epilogue asking the same question.

Such is the frame work for the brilliantly constructed The Merchant of Venice, the only opera written by pianist and composer, André Tchaikowsky. This incisive and beautifully calibrated adaptation of Shakespeare’s most disturbing of comedies is ripe for production on this side of the Atlantic, if indeed the post-pandemic era spurs a renewed appetite for genius.

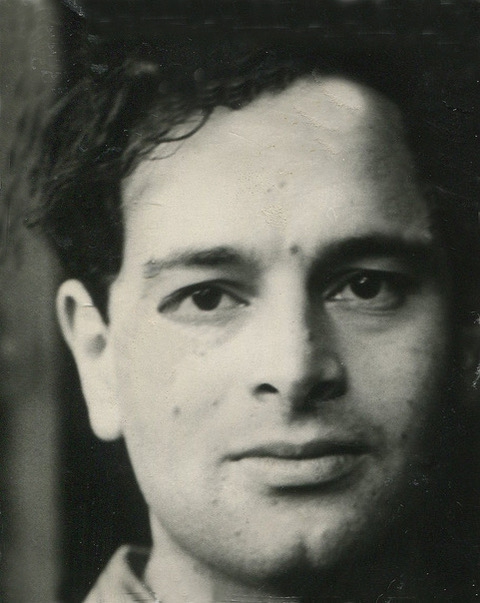

Born Robert Andrzej Krautnammer in 1935 into a Jewish family in Warsaw, Tchaikowsky began playing the piano at age four under the tutelage of his mother, herself an amateur pianist. At the onset of the Second World War he and his family were moved to the Warsaw Ghetto from which he escaped with forged papers under the assumed name of Andrej Czajkowski, later changed to Tchaikowsky. Subsequently he was released from the transit camp at Pruszków as a regular Pol. His mother was rounded up in the Warsaw Ghetto and sent to Treblinka, where she died.

Known primarily as a pianist in the late 50’s, Tchaikowsky toured internationally under the aegis of legendary impresario Sol Hurok. He recorded works by Bach, Mozart and Chopin among others, for RCA Victor and Columbia EMI. His abiding interest in composition was encouraged by consultation with Nadia Boulanger at Fountainbleu. In 1957, during his time with the esteemed instructor, he gave a series of recitals in Paris performing the complete piano works of Ravel to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the French composer’s death.

Throughout his career his dedication to Shakespeare was unwavering. It was said that he could recite extended passages from Shakespeare’s work with eloquence often surpassing that of cultivated speakers in his England, his adopted homeland.

Tchaikowsky’s output as a composer was particularly impressive considering that he composed during his work with Boulanger and while performing. Notable among his compositions are the Piano Concerto No. 2, Inventions for Piano, and String Quartet No. 1. In addition to The Merchant of Venice his works related to Shakespeare included settings of seven Sonnets for voice, songs for The Tempest, and incidental music for Hamlet. He recorded several of his own compositions for the EMI label.

Theater director John O’Brien wrote the libretto for The Merchant of Venice, adhering closely to Shakespeare’s text. The opera was composed between 1968 and l982 but was mostly complete by 1978. Tchaikowsky had been corresponding with Lord Harewood, then director of the English National Opera, and a play-through of the first two acts was arranged. Harwood attended along with ENO artistic director David Pountney, who would eventually move to Austria’s Bregenz Festival, and Sir Mark Elder, director of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. In March 1982, Harewood declined to produce the opera, a rejection that was followed by Tchaikowsky’s death from colon cancer three months later.

It remains the only recording of the full work currently available, and should command the attention of anyone interested in contemporary opera and its societal relevance.

The opera languished unperformed until Pountney, faced with replacing a delayed commission at Bregenz, scheduled it for the 2013 festival. It was a last-minute affair that nonetheless was sharply directed by Keith Warner, who placed the work in the Edwardian era and cast it with a group of superb singers who were ideally suited to Tchaikowsky’s dense and complicated score. Sets by Ashley Martin-Davis evoked the secretive world of finance, giving way to surroundings both stark and tranquil and bringing visceral excitement to the work’s vaulting moods. Davis’s costumes, bowing to Edwardian formality offered dashes of color and subdued wit. Erik Nielsen conducted the Vienna Symphony in an expressive reading that realizes the full power of the composition.

Despite the noise, it hasn’t been heard from since.

A co-production with the Adam Micklewicz Institute as part of the Polska program and Teatr Wielki, Warsaw and the Welsh National Opera, the Bregenz production was recorded on DVD by Unitel Classica. It was released by EuroArts Music (#2072708), with an illuminating documentary that tracks the details of production from costume fittings and set design, down to the harvesting of a tree for use in the epilogue. Exploring the evolution of the principal sings is particularly fascinating.

The DVD of the performance captures the finely tuned characterizations with effective camerawork, and shows the stagecraft to its best advantage. It remains the only recording of the full work currently available, and should command the attention of anyone interested in contemporary opera and its societal relevance. In A Musician Divided: André Tchaikowsky In His Own Words, Pountney commented that after the ENO rejection he was once a part of the silence surrounding The Merchant of Venice, but now after its triumph at Bregenz he proclaims, “I am part of the noise.”

The opera made noise in Tchaikowsky’s hometown when the Polish production opened in October 2014. The distinguished African-American baritone Lester Lynch assumed the role of Shylock originated by Adrian Eröd in Bregenz, introducing a racial element that added new complexity to the opera’s already top-loaded social and religious schism. Lynch was joined by Lauren Michelle, the young African-American soprano playing Shylock’s daughter, when the production moved to the Welsh National Opera in 2016, where both made their company debuts. Previously Michelle had won the 2015 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition and Lynch received rave review for his Shylock in Warsaw. They appeared when the company presented it for two performances in London at the Royal Opera House in July of the following year.

Despite the noise, it hasn’t been heard from since.

The electrifying atonality of the first act makes perfect dramatic sense. Challenging music is draped in great theater. Any semblance of harmony would undermine the unrelenting distaste Antonio feels for the Jewish Shylock and the hate that festers at the money-lender’s core. Antonio’s suppressed desire for Bassanio, clearly the source of his melancholy, is firmly established in the Bregenz production. Antonio will risk pledging a potentially fatal pound of flesh, Shylock’s demand if he defaults on the loan of 3000 ducats, so that Bassanio will have the means to win the hand of the heiress Portia.

The singers individually and as an ensemble create overwhelming tension and catharsis through music that is spectacularly abstract.

Tchaikowsky’s assignment of vocal types to these characters shows his thorough understanding of their singular sounds and the theatricality of their aural interaction. Counter-tenor Christopher Ainslie as Bregenz’s Antonio produces darkly shaded tones that are crisp and agile as he maneuvers a role suited to the delicacy and vocal heft of his singing. There are moments when one could come away thinking the opera’s central character is the depressive of Venice. Charles Workman’s assured and penetrating tenor projects Bassanio’s jovial self-possession and a fawning gratitude that feels more like selfish relief. Eröd’s baritone retains its grandeur and polish even as Shylock contorts it into vocal fits of rage and resentment. Shylock, as the world knows, is not likable. Few of the characters in the opera are but Eröd makes Shylock at least understandable. His extraordinary diction is a gift to O’Brien’s potent libretto.

Fleeting moments of languid romance appear later in the act between Jessica, Shylock’s daughter and her Gentile lover, Lorenzo. Surrealistic trappings temper the romance with Jessica atop a wall of safety deposit boxes and Lorenzo below. Their open umbrellas touchingly meet and when closed join handles. This mildly suggestive gesture appears to facilitate the transfer to Lorenzo of a bag of ducats and jewels. The atmosphere turns tense as they run off together. Rage consumes the setting when Shylock discovers that Jessica has escaped his clutches with a Gentile and, perhaps even worse, with the ducats and jewels. Kathryn Lewek’s lovely and formidable coloratura is attractively paired with the supple tenor of Jason Bridges projecting a rhapsodic if guarded optimism with their swaying body language.

Belmont is a heady place where Portia and her maid/friend Nerissa lounge on the riverbank contemplating suitors and marriage at the beginning of the second act. They await the arrival of a series of princes who, in order to win her hand and fortune, must negotiate a maze and select among three vaults, gold, silver and lead, the one which contains Portia’s portrait. Magdalena Anna Hofmann is a marvel as Portia. An elegant low ranged soprano, Hoffman’s hauteur switches to cunning when she transforms from pampered heiress to shrewd lawyer in the third act. But before all of that she and the energetic mezzo-soprano Verena Gunz as Nerissa make a refreshingly giddy pair.

The first to arrive at Belmont is the opulent and acrobatic Prince of Morocco, who literally catapults to the gold vault. Then enters the preening Prince of Aragon, more like a Keystone Cop who pratfalls his way to the silver. Both leave empty handed. Bassanio arrives with his friend Gratiano, the hearty baritone David Stout, and with some festive prompting from Portia’s household staff and Belmont villagers, selects the lead vault and wins Portia’s hand. Nerissa and Gratiano, prone to suggestion, decide to marry as well.

All is joyful but not for long. News arrives that Antonio ships may be lost a sea thus causing him to default on Shylock’s loan. Fearing for his friend’s life, Antonio rushes back to Venice and the start of the unnerving third act in the courtroom of the Duke of Venice, a scene of high musical drama.

Antonio is grim and resigned. Bassanio pleads that Antonio can repay the debt since his ships have arrived safely and offers to triple the payment now that he’s flush with Portia’s fortune. Shylock rants and states his case proclaiming with demented logic that it is his right to collect Antonio’s pound of flesh because the payment is late. Even the Duke cannot dissuade him. Antonio prepares to die, Shylock produces his scale and scalpel and the disguised Portia finds the loophole and requests Bassanio’s wedding ring as payment for her services. Narissa, disguised as her clerk, follows suit.

It’s time for it to rattle the operatic cage and make some noise over here.

The outcome is well known, but the operatic opportunities of Tchaikowsky’s composition are not. The fast pace in the courtroom is genuinely thrilling. The singers individually and as an ensemble create overwhelming tension and catharsis through music that is spectacularly abstract.

Under a full moon at Belmont the epilogue unfolds. Mozart, rather than Shakespeare, comes to mind with “Ah, tutti contenting saremo così” from the closing moments of Le nozze di Figaro. The woman, alluringly clad in short night shirts, receive their husbands with some disdain. The couples resolve the issue of the missing wedding rings as truth and insight permeate the night. Antonio appears and they are all glad to see him but they wander off together, followed by Jessica and Lorenzo who have charted their course, leaving him alone. Freud and his chaise lounge appear. Antonio sits, then stands and stares at the moon in silence.

This is a beautifully sad end to the opera, but hopefully not for it. Verdi, for whom Shakespeare was a frequent source of inspiration, developed an enduring musical means of conveying his stories and explorations of human nature. Tchaikowsky does no less. He examines the most complex aspects of humanity in a musical context that evokes the tumult of our world. We can only guess what operas might have followed, had his life not been cut short. Shakespeare’s more enigmatic and unsympathetic characters might have attracted him. But what we have here is engrossing theater and the very essence of contemporary music.

The Merchant of Venice has made impressive noise in Europe. It’s time for it to rattle the operatic cage and make some noise over here.

Comments