Am I allowed to hate Silent Night?

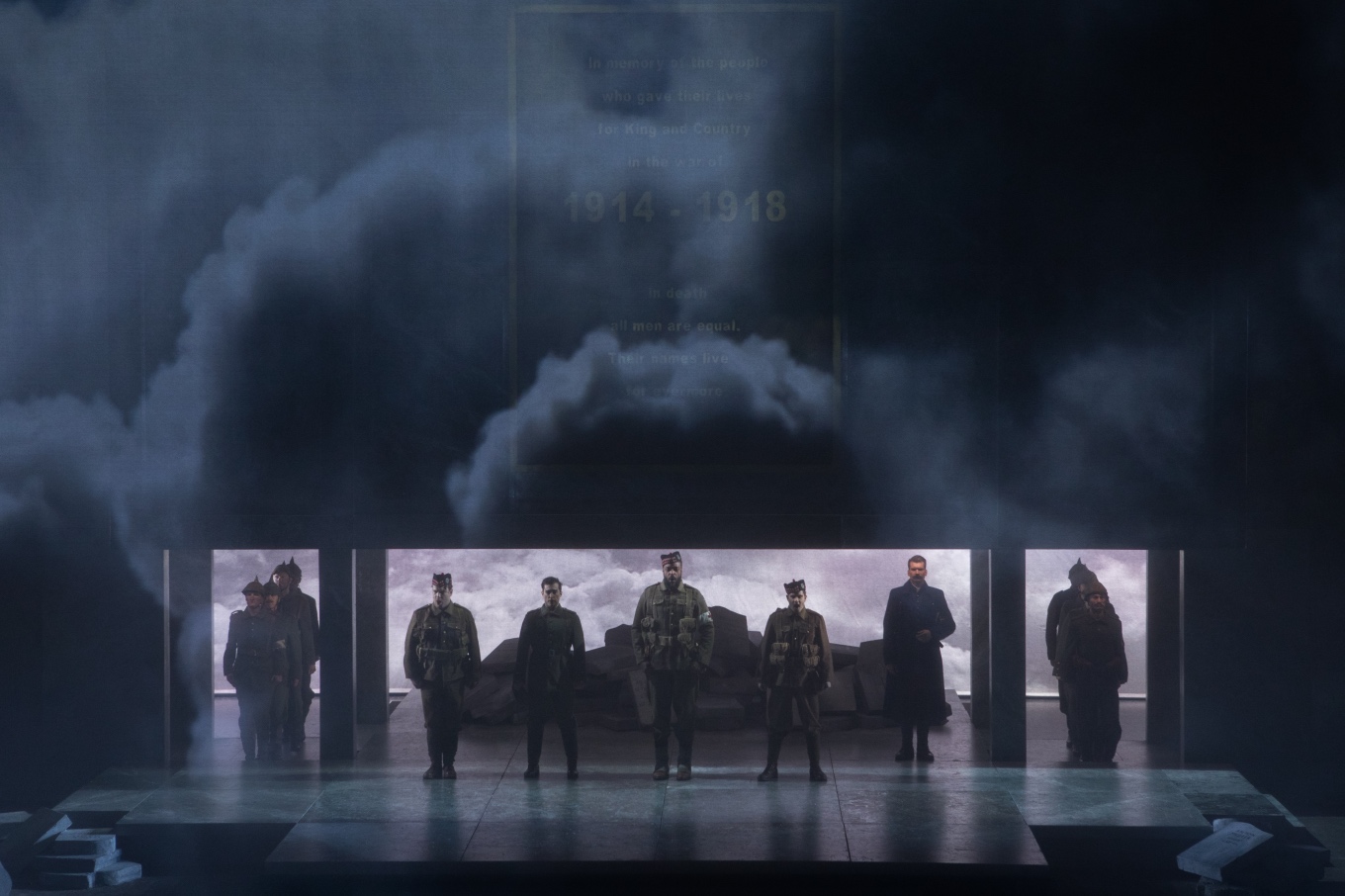

ReviewOn the eve of the 100th anniversary of the armistice which ended the First World War, audiences who walked into the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater were presented with an ever-scrolling list of names and dates projected on a screen at the stage’s proscenium - the names of the men, in the hundreds of thousands, who were killed in the most violent military conflict mankind had ever engaged in. This, among other elements of Tomer Zvulun’s new production of Silent Night, winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for music composed by Kevin Puts on a libretto by Mark Campbell, lets the piece serve as much as a memorial than simply a piece of theater. But this aspect of it made me feel conflicted about it as a critic; I found myself thinking, am I allowed to hate this piece as much as I do?

And I’m sorry, but I did hate it. These are words I’ve almost never uttered about an opera, and it doesn’t feel good to be typing them now. The work’s overall message - that if we can only see the humanity in our opponents, then we might be able to put an end to the violence of war - rings hollow when the fascism and authoritarianism that rose out of the ashes of the Great War (something the libretto only acknowledges in passing) are looming once again in the 21st century. In a review of the 2005 film on which Puts based his opera, New York Times film critic Stephen Holden wrote, “Why does Joyeux Noël … feel as squishy and vague as a handsome greeting card declaring peace on earth? Maybe it’s because the kind of wars being fought in the 21st century involve religious, ideological and economic differences that go much deeper and feel more resistant to resolution than the European territorial disputes and power struggles that precipitated World War I.” And this assessment is fitting for the opera as well.

It’s worth noting that the spontaneous Christmas Truces, in which soldiers from opposite sides of the conflict came together to rest, exchange gifts, sing carols, and bury their dead, while widespread in the first winter of World War I were largely not repeated in subsequent years as the conflict continued. Even though these men paused to shake hands and break bread, they soon went back to killing and dying. It reminds me of a phenomenon that you may have noticed if you follow a lot of classical musicians, and classical music adjacent accounts on social media, whenever tragedy strikes, people start quoting Leonard Bernstein.

“This shall be our reply to violence,” the famed composer and conductor famously said in the wake of the assassination of president Kennedy, “to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

It sounds lovely, but the 5th or 6th time you see that quote following a school shooting or terrorist attack, you start to think, maybe we should come up with a more effective “reply to violence,” because this clearly isn’t working.

In Silent Night the central character is an operatic tenor, Nikolaus Sprink, performed admirably by real-life tenor Alexander McKissick. Sprink echos the Bernsteinian sentiment. He wonders whether the artform he had dedicated his life to before the outbreak of war has any real value while boys are dying senselessly in the trenches. But when he witnesses how it is the singing of folksongs and Christmas carols that encourages soldiers to lay down their weapons and share a drink together in no-man’s land, he has a change of heart.

But that’s not all. Sprink, of course, has a love interest: Anna Sørensen, whom he reunites with when he is ordered to sing at an officers’ Christmas party and then, bizarrely, brings her with him back to the front. Sung by soprano Raquel Gonzàlez, a with a clear and sweet tone that skillfully navigated Puts’ difficult score and overbearing orchestration in a role that somehow lays both too high and too low, Sørensen’s character seems out of place (and I suppose that’s because she literally is) and it feels as though she was wedged into the story as an afterthought. In the denouement when Sprink and Sørensen defect and then give themselves over to the enemy, Sprink says it’s because he can’t fight a war if it means being apart from her, which I found infuriating, when the whole story seemed to be building up to a declaration of “I can’t fight a war if it means taking up arms against these men whom I have befriended.”

Many of the singers seemed to struggle with Puts’ vocal writing which, for the men especially, fell mostly in the lower ends of their vocal ranges, and the cast of soldiers growled and barked through the opera. This was particularly frustrating during an aria sung by baritone Christian Bowers as the French soldier Ponchel. In the aria, Ponchel is reflecting on his life at home and his affection for his mother, Bowers’ vocal coloring lacked the tenderness called for by the text and orchestration, a problem I think would have been solved by a higher tessatura. As a Scottish soldier Jonathan Dale mourning his fallen brother, tenor Arnold Livingston Geis did manage an affecting tone; his letters home which he wrote on behalf of himself and his brother, not having the heart to give his mother the sad news, were some of the only truly moving moments of the opera. Also of note: Aleksey Bogdanov, who brought strong characterization to the stodgy Lt. Horstmayer; Patrick Cook, who lent a gleaming, steely voice to the preening Kronpriz; and Timothy Bruno who embodied detached stoicism in the role of the French General.

While the overarching themes of Tomer Zvulun’s production were heavy handed, including heaps of tombstones scattered about the set, scene-setting postcards from various parts of Europe projected against a screen to introduce each setting, an enormous WWI memorial plaque descending upon the opera’s conclusion, and, of course, a surprise patch of poppies, the small-scale directing of the cast of singing actors was spot on. With such a large ensemble cast, Mark Campbell’s libretto leaves little room for development of character depth, and Zvulun’s directing made up for it and imbued each character with a lived-in quality.

In the pit, conductor Nicole Paiement skillfully led the WNO orchestra through Puts’ difficult score which quickly transitions from a convincing imitation of classical 18th-century opera to modern neo-romantic soundscapes to folk styles (complete with Scottish bagpipes!), to a sweeping funeral march reminiscent of Wagner’s famous funeral march in Götterdämmerung, which was another highlight of the evening.

At the conclusion of Kevin Puts’ Silent Night, military leadership on each side catches wind of the fraternization at the front, and each unit is reassigned. They can’t possibly fight each other anymore, now that they’ve become friends. But how could they fight anyone after the experience they shared that Christmas of 1914? If you can’t extrapolate the humanity of one German soldier onto all soldiers of any kind anywhere then what’s the point? And should you? As the world would see 25 years later, some soldiers are truly bad people fighting for truly evil causes.

Perhaps it’s fitting that Silent Night feels more like a living memorial than as a piece of theater. I walked in expecting the latter, and found myself rolling my eyes at the schlocky heavy-handedness of the production. But then somewhere in the middle of the second act I noticed a man in front of me, in a military-style haircut, crying and wiping his face with a handkerchief. He was clearly very moved by this piece which I had dismissed. Am I allowed to hate this as much as I do? Maybe. But that won’t stop others from finding comfort in it.

Comments