Tales from the score: Deh vieni, non tardar

How-toSusanna’s aria from the final act of Le nozze di Figaro is constantly fascinating. At its simplest, it’s a seductive call into the dark for her lover. Yet, Susanna has planned this tryst with the Countess; they are disguised as each other, hoping to trap the Count in his dirty ways. To complicate things further, Figaro has heard about Susanna’s plans, and Susanna has heard that Figaro has heard. This aria is a layers-thick trick, which Susanna sings to Figaro, making him think she’s singing to the Count (and enjoying it).

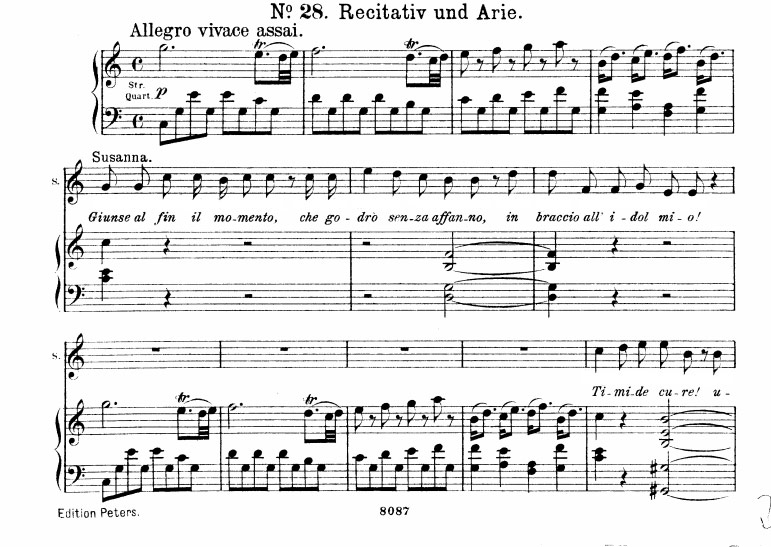

So, this aria is all at once a) a lie, b) a true seduction of Figaro, and c) Susanna in disguise. That latter part informs the music, which looks and sounds much more Countess-like than like Susanna. For instance, she gets an extended accompagnato recit, a device largely reserved for noble characters instead of maids:

There’s Classical grace in this opening, very round, very symmetrical. The key belies Susanna’s station a little bit; keys like C, G, and F major are popular picks for Mozart’s soubrettes (think Despina and Zerlina, compared to Fiordiligi and Donna Anna). Yet the accompagnato form makes Susanna speak a little slower than the rapid patter she’s had for much of the opera; she delivers organized, calm thoughts in a collected way. She even uses some lower, Countess-inspired notes to get the infusion of lust into this recit; words like “foco” and “notte” couldn’t be sexier:

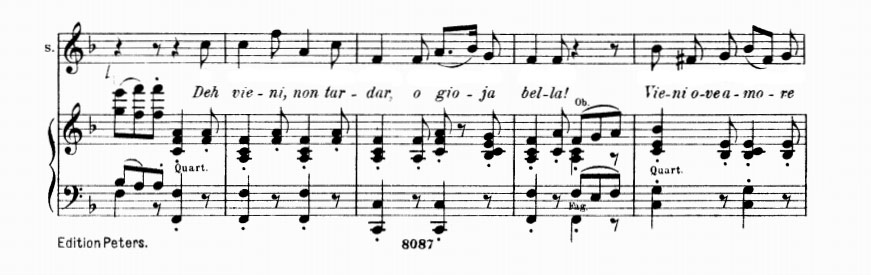

Again, Susanna sings a rich woman’s aria in a poor woman’s key. There’s a simple dance rhythm inherent in the 6⁄8 meter, but it’s controlled, not improvisatory or perky. The passing F-sharp in “Vieni ove amore” is just the kind of subtle sexuality that the Countess would infuse in her words; it’s almost as though Susanna is playing dress-up, recalling the few moments of flirtation she heard from the Countess and trying them on herself.

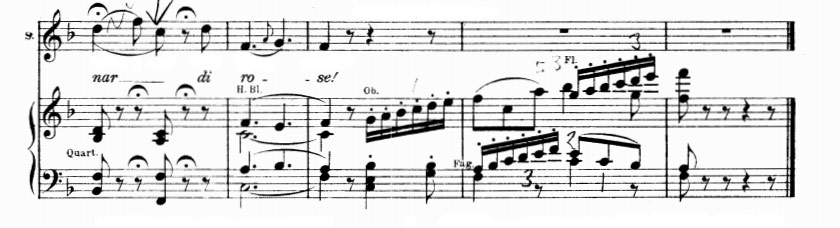

These long “vieni’s” (below) are similar to the Countess’ “Porgi, amor”, and the dramatic difference between the two arias is rich with meaning. For the Countess, those long notes meant yearning and wishing; for Susanna, they’re lures for her lover. Similar, yet very different. The two phrases on “ti vo’ la fronte incoronar” are totally regal and womanly; even the brief moment of coloratura is controlled and thought out.

Finally, the end of this aria is like a very expensive gift, wrapped in an expensive bow. It’s the opposite of showing off, despite the small cadenza Susanna sings on the last “incoronar”. Instead, it’s making her audience (Figaro, the Count, whoever) yearn for more; it’s as if Susanna has just sung the first verse of what could be a hot, hot duet.

This aria is so often sung that we can become immune to its effect in the context of the entire opera. It’s incredibly difficult to play all the musical and dramatic layers when singing the aria alone in an audition or concert. But it can be tons of fun to pretend (to pretend to pretend, really) that Susanna is imagining herself a Real Lady, and finally gets the chance to try it out. It’s very Eliza Doolittle, when you think about it.

For more, check out our “Deh vieni, non tardar” Aria Guide.

Comments