Interviewing the Greats: Virginia Zeani

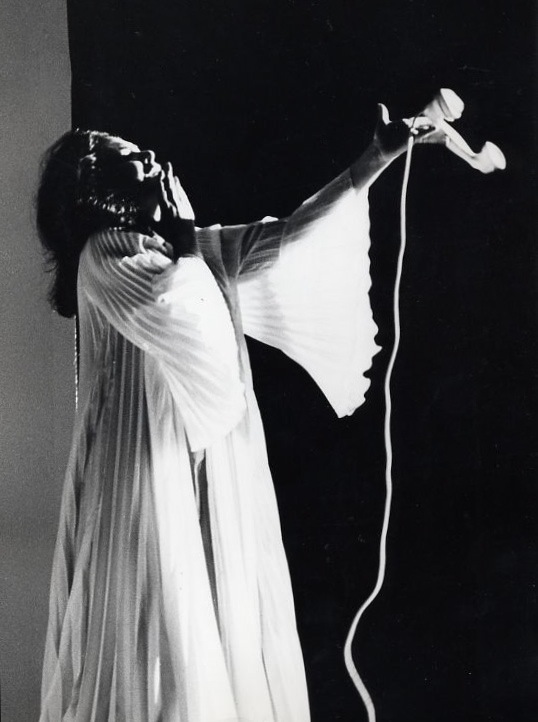

InterviewIt is no wonder that opera collectors call Romanian soprano Virginia Zeani “l’Assoluta.”

In May 1948, Zeani made her stage début in Bologna, singing Violetta in La traviata; she went on as a last minute replacement, never having sung with orchestra and with no rehearsals. In her career, she would go on to sing 648 times. Throughout her illustrious 34 year career, Zeani’s repertoire covered 69 operas and a wide range of roles, including Lucia di Lammermoor, Gilda, Elvira (I puritani), Senta, Aida and Magda Sorel (The Consul). She sang all three female leads of The Tales of Hoffmann in the same performance, and in 1957 she was the premiere Blanche de la Force in Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites in Milan.

Zeani sang the stages of the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala, l’Opéra de Paris, Covent Garden and L’Opera di Roma and to sing alongside the likes of Beniamino Gigli, Franco Corelli, Alfredo Kraus, Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, Shirley Verrett and Grace Bumbry, to name a few.

After retiring from the stage in 1982, Zeani began teaching, and she held a studio at Indiana University with her husband, bass Nicola Rossi Lemeni, for 22 years. Many illustrious singers have come out of her studio, including Sylvia McNair, Angela Brown, Elizabeth Futral, Elīna Garanča, Vivica Genaux and Ailyn Perez.

At 89 years of age, her ravishing green eyes light up to the slightest mention of music and her warm heart is always ready to share its wisdom with whoever is willing to listen.

1. How did you find yourself, having been born in a small village in Transylvania, to sing on some of the greatest stages around the world?

I had a very strange destiny. I started very young, I studied very hard and I never loved anything more than singing. I think it is something that has to be born with you. You never know what will be happening next but something, or somebody, guides you towards what you love but don’t necessarily understand, and that gives you the power to to invest time and energy into discovering what is your calling in life. The fact that you have this ambition to learn about something is a mystery, but at the same time it’s a joy to pursue something that you love which is, in the end, not really attainable. How does one “accomplish” music?

So, from the time that I was a child I loved singing and I would imitate all the birds and everything I would hear in the garden. I started at 13 and they believed that I was a mezzo soprano, then they thought I was lyric soprano, then a lyric with coloratura. The destination of my desire was always a mystery, but the attraction I had towards singing made me want to pursue that desire every single day. I knew that my destiny was to sing.

2. What should a young singer do to assure a healthy transition between studies and the professional life of a singer?

I think the most important trick is to take it day by day and not to exaggerate. After that you have to try your best with the talent you have at the point where you are. You can’t decide what you will be before arriving there, when you are still young and always changing. Even after training for all those years, your voice will change and you need to have the patience not to ruin your beautiful natural talent in wanting to go too fast. Slow and steady wins the race.

What you can do, though, is that when you do get there, be sure you are prepared to conquer whatever challenge that is presented to you. I think the most dangerous behaviour that I still see in young singers is that they have no patience to study. They go very fast by imitating what they hear either on stage or on recordings and they alter the color of their sound rather than study with calm and patience.

3. What are the big differences between opera today and when you were active on the stage?

The biggest difference is the matter of stage direction. Nowadays, some stage directors change everything: they don’t leave the operas to be told as the composers wanted them. They try to modernize the subject, which to me is absurd because I think the opera is connected to the composer, the time in which it was composed and themoment of history that was captured in that particular story. In my time, we were the ones who, most of the time, staged the productions we were to appear in. It was really a team effort between the singers, the conductor, the stage director and the work that was given to us. We would work hand in hand to try and find what the composer would was trying to communicate with the music rather than trying to find a way to make these masterpieces “exciting”: they already are, in so many ways.

I cannot stand seeing a Rigoletto production set in Las Vegas because they do it only to attract younger audiences, and I don’t think that it is what will make them want to see Rigoletto; they want to catch a glimpse of the past and enter the world of this amazing character! They know what the present is, they need to know what the past was, what romance was in the times when these characters lived. If you are doing this opera, you have to study the characters created by Hugo, Piave and Verdi. There is enough information in what they have given us and no need to invent anything new. The public then can experience the imaginary universe created by these geniuses and let their own imagination go free.

4. Why do you think that directors go towards sexuality and violence in order to attract younger audiences to the opera?

The problem is that young people today aren’t necessarily exposed to things that have romance and beauty, it is, by many, considered to be outdated. They live in a world where violence, opulence, artificialism and vulgarity is far too present and so they are not sensitive to the beautiful things in life, which then makes it hard to appreciate them. To take the time to listen and appreciate beauty gives the ambition to create it afterwards.

5. What is your answer to those who say that opera is a dying artform?

Art cannot die. Dante is still modern, Petrarca is still important, Sophocles, the great philosophers and mathematicians are still relevant today in their own way. There is a reason why these pieces are still played after so many years, we can always learn something new from them, as people do when they take out old books of philosophy to understand the meaning of certain things. It is in progress that goes too fast that we lose the sense of what is going forward and what is not.

6. What do you think of the attempts to modernize opera, especially the rise of Regietheater?

The taste today is very different. If you take La traviata, it was written for the taste, the ideas and the problems of the 19th century. However, if Violetta’s story was written today by a different composer, or a different writer for that matter, she would be a totally different woman; the journey would probably not be the same because you can sing love, happiness, sorrow, sadness and passion and in a thousand ways. I feel like the modern stagings, that have nothing to do with what is in the score, are a complete betrayal to the composers and librettists because they change their intentions. If Verdi wanted to do the first act of Traviata as if she were a woman like Carmen, he would have written it that way. The music represent the composer’s desire to tell a story in a certain way, which is why new works are so important.

7. You sang many world premières, including Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites and Raffaello de Banfield’s Alissa. How did you reconcile the different demands of these operas, and why was it important for you to sing them?

First of all the instrument remains the same, nothing changes other than the colors, depending of the state of mind your character. The secret is to go find the direction of the phrasing and the questions of the opera. If you take Poulenc’s works that I sang, either the Dialogues or even La voix humaine, which are not close to the bel canto in terms of style, I had to understand the very modern concepts and explain them to the public with a good sound and great diction in order to express exactly what the composer tells in his score as I would do with any opera.

The goal, in any kind of music, is to communicate, to share and the approach should be the same for all kinds of repertoire. You have to look for the phrasing, which will guide the message of the opera. You cannot use the same colors with the role of Alissa or with Blanche because the phrases and the composers are different. If you think you can bring something to a new character you should do it, absolutely. How exciting is it for an audience to hear and see someone do something that they have never heard or seen before? To have new stories is very important.

When I did Menotti’s The Consul, even if it wasn’t the world premiere, most of the audience was going to witness this piece for the first time. What they experienced was an fantastic opera full of expressivity of desperation, sorrow and depth of emotion. These elements had never been found in the same form in any other opera they could have seen, and it was very exciting for me to receive a new kind of energy coming from the audience. This is why new works are so important, it allows artists to express themselves in new ways and make the public feel and see things in a different way: it opens your heart and your spirit to new things.

8. You sang the role Violetta many, many times (in fact, exactly 648 times from 1948 to 1973). How did your portrayal of Violetta Valéry evolve and what made you stick with her for so long?

The main thing is that I loved the role. You absolutely have to love a role to sing it that many times! I loved to color Violetta’s music and her words, changing from forte to piano to mezzo forte, laughing, crying, all these things. In other words I loved the interpretation, the way it was written and the way I could play her. As far as the way she evolved through time, every performance is unique. She never evolved in a gradual way, because everything depends on the colleagues, the conductor, the staging, all things you grow from. With the years you can add more depth and discover colors that you hadn’t thought she had before, or didn’t know how to portray them, and with age this gets easier.

We always think that, over time, our feelings will evolve. In my experience, they do not: our emotions add to each other like pieces of a puzzle and give us a better understanding of our purpose in life.

9. How do you keep a fresh idea when performing a role so many times?

Darling, routine cannot exist, because when we sing it is like a conversation, or a monologue, depending on the situation. You cannot repeat a spoken phrase of even a word the same way two times in a row. You can feel the same music in a different mood, in a different sonority, but you can never repeat exactly the same thing. When repeating the same music, it is influenced by the colors of the stage, the dress you wear, the public in the opera house, the colleagues, etc. Everytime it’s a surprise, it’s new, it’s fantastic. You become the character: you can die as Violetta in many ways, depending on what you have at your disposal. It’s not a repetition mot-à-mot. It’s an interpretation with the voice that you have and with the physique that you have.

Every night was different, but not in the music. It was in the gestures, the vocality, the way I fell down… it’s alive, you cannot repeat yourself. You are always creating a new version of yourself.

10. How did you make the transition between roles that belonged to a perhaps lighter fach towards the more dramatic repertoire?

Each character has a different palate of feelings: Violetta has her own emotions, as do Magda or Aida. We have to interpret the music to the best of our abilities at the moment when we have it in our hands, or rather in our voices, which is why the interpretation can become very different over time. It is important to never force an interpretation or a feeling because if it has to come, it will in a natural way. If not, you gamble the truth and you might hurt yourself in the process.

Your way may not please everybody and it is OK, some people may go crazy about it and some may not. Expectations can be very dangerous, as they may not be realistic to what you can offer, though your interpretation may very well still be valid.

For example, many people think that to sing Mimì one must have a big, lyrical, almost heavy voice. In reality, Mimì is a young, frail girl who hasn’t experienced much in life other than suffering, loneliness and is now discovering love. The vocality has to match the colors that the character has encountered in his or her life; there is no reason for Mimì to sound like she has had the experiences of a mature woman because she has not. This comes through the vocal emission, which is why I always say to my students that with a good projection system there is no need to sing “big” or “heavy”. You can give to the public even the smallest feeling and it will travel in the opera house through your face, especially the eyes, and your voice.

11. You have interpreted many characters in different settings of their stories such as Marguerite (Faust/Mefistofele), Desdemona (Rossini/Verdi) Manon (Puccini/Massenet), how did you translate your interpretation of these characters when found in a totally different universe?

Even if the characters have a similar story, their music and their texts, which feed the interpretation, are totally different. If we take Manon: in the Massenet setting of the story everything is lighter, she is more infantile, naïve, more pure, less passionate and more elegant and sophisticated in a way. Puccini gives us a Manon full of passion and seems to understand life in a more mature way, she even seems a little older than Massenet’s Manon in my opinion. You cannot possibly interpret this character in the same way because “she” is totally different. What you have to do is take out the text, look at the music, the style and forget about the Abbé Prévost book so you can really understand the way Puccini or Massenet saw her and try your best to bring that particular version to life.

12. It seems like the term bel canto today is often defined in many different ways, however would you explain it?

Ah… it is to explain to the public every beautiful sentiment that you have in your heart. I never liked to be aggressive in my singing, especially in the bel canto repertoire. I always liked to bring every feeling through my eyes and my voice with beauty, calm and passion. You have to exchange with the public and if they understand the feelings you have and agree with them it means you are both in a total union and exchange of emotions. However, everybody is born in a different way and you will never find anyone who is exactly like you or who feels things the exact same way as you do.

This is why we have to express our feelings being faithful to the composer and the librettist, but most of all to ourselves, to our background, to our spirit. This is the reason why some people might prefer an interpretation to another one, we might feel beauty in a certain way that someone else does not understand but when we do we become very close to each other and this is one of the most beautiful things: to unite our souls through music.

From a technical point of view, here is what I call my system of singing: in Italian we say “raccogliere i suoni”. It means that you have to assemble the vibrations, the “sounds”, in a point, the mask, which allows the voice to shine as much as possible with the less effort possible, and to support those vibrations with the diaphragm. If you assemble those vibrations in that point, you will never get tired, as opposed to singing wide, open or loud, which we hear a lot of today, unfortunately. Then you have to convey emotions with those sounds, give them color and find the intention of the composer. On top of that, every voice has to be able to do everything from singing coloratura to vibrating the sounds in millions of colors and find a way of doing it with ease or else you will tire yourself tremendously. The trick is to find out what you are really good at and use it to your advantage, while you work on what needs to be improved.

Bel canto really is, in the end, a way to make every single person in the opera house, including yourself, feel the most beautiful things in the world.

Special thanks to Adina Buboi for her help co-ordinating and recording these interview sessions.

Comments