Aria guides: the Composer's Aria

How-ToFor mezzo-sopranos, there are few arias that are as exhilarating to sing as the Composer’s Aria from Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos. It’s brisk, colourful, more than a little meta in subject matter, and it’s a trouser role to boot. It’s a densely packed aria that shows off your goods, and there’s a fine line to tread between singing beautifully in the way that Strauss so often asks for, and pushing your voice into the realm of screaming.

This aria is tricky to learn, but tons of fun when it starts to sit right. With the work you do in the practice room and with your teachers and coaches, our latest Aria Guide will help you navigate the score and pace yourself in style.

- Much of this aria will be easier to sing if you think of it in 2⁄2, rather than 4⁄4. This opening section can feel a bit square, but it’s really about channeling masculine energy. The first couple of phrases should sound a bit like someone who’s just splashed some refreshing cold water on their face. Be diligent about holding “gut” for all four beats, and don’t plan to take a breath in the little eighth rest in “Ich sehe jetzt alles mit anderen Augen!”

- Take advantage of the [i] vowels in “Die Tiefen” as you figure out where to put these low Cs; if they don’t have to be entirely done in chest voice, it’ll make for a smoother rest of the phrase. The funky off-beats that Strauss writes on “Daseins sind unermeßlich” should feel a bit jazzy; maintain that sense of 2 beats to the bar, to help you avoid slowing the tempo down in the off-beats.

- Even when you get square rhythms like this one - simple quarter and half notes - make sure it’s still about speaking German. When you sing, “Es gibt manches auf der Welt,” the quarter notes are all set to fairly weak syllables; that means that as deliberate as they may look on the page, those quarter notes need to really lead forward, connecting “manches” and “Welt”.

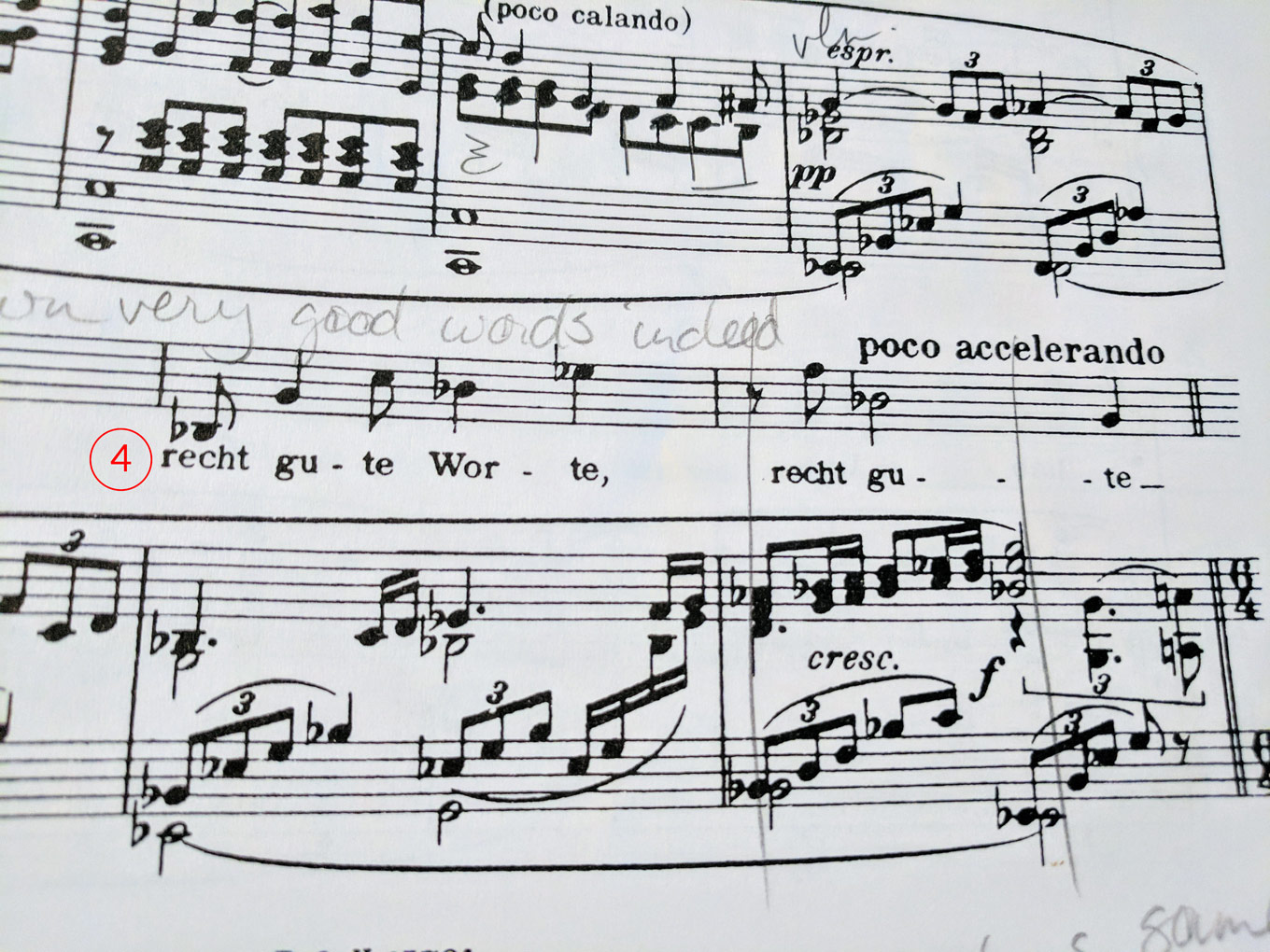

- Don’t work too hard for this “recht” on the low B-flat; in the big scheme of things, punching out a loud low note is less important than keeping your voice agile and spinning. There’s a fun metric transition into 6⁄4 that happens over the page, and it starts at the end of this line with the octave Gs and A-naturals at the end of the poco accelerando bar. Read on for context…

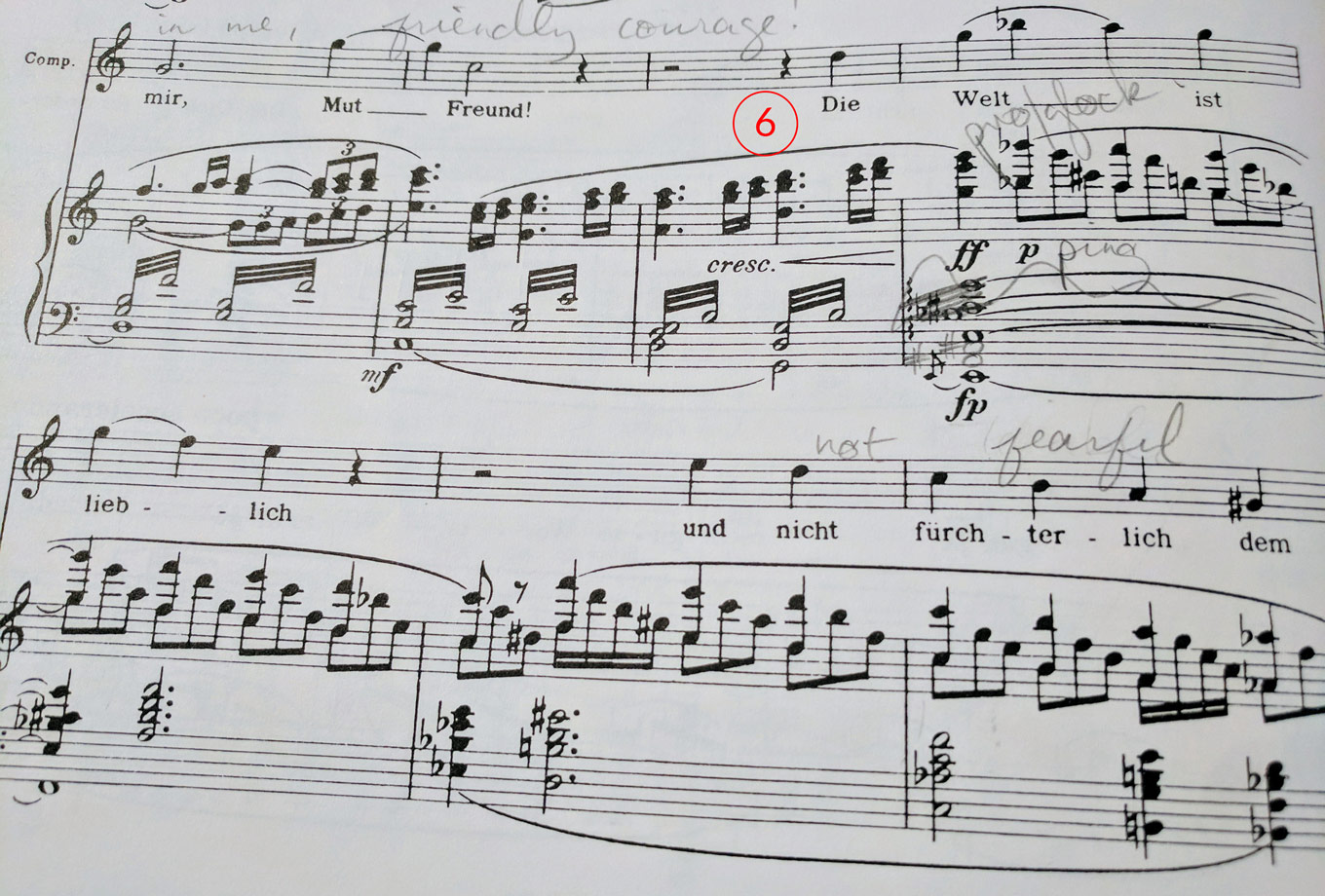

- We’ve gone from 4⁄4 (or 2⁄2) to 6⁄4, and the best way of feeling it is to treat the half-bar the same in both meters. Basically, a conductor can keep the same tempo of 2 beats to the bar between the 4⁄4 section and this new 6⁄4. In the context of the whole opera this transition is a bit easier, since the tune in the right hand of the piano is heard elsewhere in the score and it’s more recognizable; when you’re working on the aria on its own, be sure that you get the subdivision of the 6⁄4 measures as being in 2, and not in 3. The next transition, at “Mut”, should be another seamless motion from 6⁄4 to 2⁄2, both of which can be conducted in 2.

- This high B-flat on “Welt” is one of those moments where the high note feels like a big deal to you, the singer, but it’s not a monumental moment for the listeners. It’s certainly exciting, and often singers take a tiny bit of extra time to spend up on the B-flat, but the note is part of a larger phrase that continues forward, so it’s not a “big moment” per se.

- The tempo relaxes here, and you can help it along by giving two great, spinning vowels on “Musik”. As you settle into the new tempo (marked etwas ruhiger, so not dramatically slower), it still works better if you think of it in 2. It’s a place to coast a bit vocally, and conserve some energy for the next page; thinking in 2 rather than 4 will put you in a more forward-moving place that more easily builds to the crash-bang finale around the corner.

- These quarter-note triplets are another place where the rhythm is more about finding the ebb and flow of the German language. You you can find some flexibility in this triplet rhythm so it sound more like speech, and you can certainly do a bit of an accelerando into the high A on “Thron” to give you a bit more room to sing it. This is place where it can be hard to decide where to breathe. Experiment with various breathing options to find out what’s most comfortable, and make sure that you’re not actually breathing too often; it’s about knowing which breaths really count, and making sure you’re comfortably out of air right before those moments.

- Quick note: some people are of the opinion that the pitch on “die” should be a D, not a C; it’s something to be aware of and cross-check with a full score, particularly if you’re preparing the whole role for a production.

- You’ll likely want to grab a good breath before “unter den Künsten”, and it’s one of those spots where the breath counts. It’ll be a quick breath no matter how you cut it, but you can carve out a good amount of time by cutting off “heilige” as early as you can, and coming it a bit late for “unter”. Take care that when you come back in on “unter den Künsten” that the first couple of pitches are sitting in a high spot, ready to give you lots of room to spin that long G.

- Practice this line in reverse as you learn it, starting from the high B-flat. It’s a good way for you to find out what kind of space you need for the high note, and what that means for how you start the low B-flat. The word “heilige” can be a bit of a trap; the combination of the letter H and the [ae] diphthong can make some singers want to swallow the word a bit, or sound it farther back in the throat (maybe in an effort to sound bigger and more masculine). Instead, take a cue from the bright, forward spin of the word “die”, and keep that [a] vowel of “heilige” in a similar place. It’s absolutely a spot to work with your teacher, since there’s a major difference in what happens over that octave-wide transition; just don’t get dark or “woofy” too soon.

- When this aria is done as a stand-alone piece, most singers opt to finish it at the end of this first bar, after “Musik!” It’s worth noting - for singers and pianists alike - that some like to continue to the end of the act (which is just about a page away). It’s a less clean ending to do it this way, but depending on the context of where you’re singing it (auditioning for the role, for example), it might be worth learning the remaining pages for good measure.

Do you have an aria you’d like to see featured in our Aria Guides series? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch at [email protected].

Comments